Community Health Worker Assessment and Improvement Matrix (CHW AIM)

Updated Program Functionality

Matrix for Optimizing Community

Health Programs

Contributing Authors:

Community Health Impact Coalition: Madeleine Ballard, Matthew Bonds (PIVOT), Jodi-Ann Burey (Village

Reach), Jennifer Foth (Living Goods), Kevin Fiori (Integrate), Isaac Holeman (Medic Mobile), Ari Johnson (Muso),

Serah Malaba (Living Goods), Daniel Palazuelos (PIH), Mallika Raghavan (Last Mile Health), Ash Rogers (Lwala),

and Ryan Schwarz (Possible)

Initiatives Inc.: Rebecca Furth and Joyce Lyons (CHW Central)

UNICEF: Hannah Sarah F. Dini and Jérôme Pfaffmann Zambruni

USAID: Troy Jacobs and Nazo Kureshy

This toolkit builds on the original work (“Community Health Worker Assessment and Improvement Matrix (CHW AIM): A Toolkit for Improving CHW Programs

and Services”) prepared by Initiatives Inc. and University Research Co., LLC (URC) for review by the United States Agency for International Development

(USAID). It was authored by Lauren Crigler, Initiatives Inc. Kathleen Hill, University Research Co., LLC, Rebecca Furth, Initiatives Inc., and Donna Bjerregaard,

Initiatives Inc. CHW AIM was originally developed under the USAID Health Care Improvement Project, made possible by the generous support of the American

people.

Design: Sonder Design

Released: December 2018

1

Background and Opportunity

As the global community aims to fulfill its commitments to the UN Sustainable Development

Goals, and the achievement of universal health coverage, dozens of countries have committed to

the expansion of community health workers (CHWs) as the front line of their healthcare systems

[1, 2]. !Robust research demonstrates CHWs improve access to care, reduce maternal, newborn,

and child mortality, improve clinical outcomes for chronic diseases, and prevent disease

outbreaks [3].

But there remains an important opportunity to improve the status quo approach to

implementing national-scale CHW programs. While ample, high-quality evidence exists that

small-scale CHW programs can reduce morbidity and mortality [4], three studies of CHW scale-up

conducted in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, and Malawi in 2016 documented limited access, quality, and

mortality impact [5-7]. The impact of these programs, and those of the dozens of other countries

currently revamping their own national CHW programs, could be optimized if the most recent

evidence and global best practices were incorporated into design and implementation [8-11].

To support the operationalization of quality CHW program design and implementation, USAID,

UNICEF, the Community Health Impact Coalition, and Initiatives Inc. have updated and adapted

the Community Health Worker Assessment and Improvement Matrix (CHW AIM) Program

Functionality Matrix [12]. This tool can be used to identify design and implementation gaps in

both small- and national-scale CHW programs, and close gaps in policy and practice.

2

CHW AIM

The USAID Health Care Improvement (HCI) Project developed the

CHW AIM Toolkit in 2011 to help organizations assess community

health program functionality and improve program performance.

Built around a core of 15 components, the original CHW AIM

toolkit was framed around two key resources: a Program

Functionality Matrix to assess the effectiveness of a CHW

program’s design and a Service Intervention Matrix to determine

how CHW service delivery aligns with program and national

guidelines [13]. A Facilitator’s Guide was also included to support

utilization of the toolkit by practitioners.

Since 2011, investment in CHW-led health delivery has continued

to grow and the body of evidence related to CHW effectiveness

has also expanded considerably. Therefore, this update of the

CHW AIM Functionality Matrix was undertaken to incorporate

current evidence on CHW program efficacy and effectiveness

[14-19], the latest syntheses of practitioner expertise [20-22], and

to improve the usability of the tool. This updated version of the

CHW AIM Functionality Matrix is intended to complement the 2018

WHO guideline on health policy and system support to optimize

community-based health worker programmes and integrate with

existing domain-specific tools for optimizing CHW programs (e.g.

UNICEF/MSH’s Community Health Planning and Costing Tool).

[23, 24, 25] As with the original AIM tool, this updated version is

intended to capacitate the processes of programmatic design,

planning, assessment, and improvement, for stakeholders ranging

from local NGOs, to national policymakers and planners, to global

stakeholders (Figure 1).

Users

National

Ministries of

Health

International

Organizations

Local NGOs

staff

Figure 1: adapted from CHW AIM, 2013 edition [13]

3

Uses

Survey

Compare CHW

services provided

by the national

goverment and

NGOs to identify

gaps and needs.

Survey multiple

programs across

countries

Planning

and review

Inform and review

CHW program

design

Assessment

Assess a CHW

program in its

entirety, within a

district or region

and/or over time

Improvement

Guide action

planning and

improvement

Capacity

Building

Orient program

to the issues

and elements they

need to consider

in planning,

managing and

assesing a CHW

program

Methods

In 2018, USAID, UNICEF, the Community Health Impact Coalition, and Initiatives Inc. undertook a review and

updating process of the CHW AIM Tool. This process entailed updating the CHW AIM Program Functionality Matrix,

however, did not include revisions to the original CHW AIM Intervention Matrices or Facilitator’s Guide which can

be found at http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/toolkit/54/en/.

Prior to updating the Program Functionality Matrix, a systematic search for other tools intended to aid

policymakers and/or practitioners in community health worker program and policy design and implementation

was carried out; see Appendix I for search strategy and databases searched. Over 200 documents were close-read

for inclusion. Relevant tools identified were linked in the appropriate sections of the revised Functionality Matrix.

To enhance the usability of the tool, efforts to streamline the program components reduced the previous fi"een

components to ten (see next page). To update the criteria for each of the components, the latest reviews on CHW

program efficacy and effectiveness [14-17] and syntheses of practitioner expertise [20] were consulted, and

revisions were vetted across multiple stakeholders for accuracy and usability (including funders, program

implementers who applied previous versions of the toolkit, and policymakers).

4

CHW AIM 2018: Revised Programmatic Components

1. Role and Recruitment: How the community, CHW, and health system design and

achieve clarity on the CHW role and from where the CHW is identified and selected.

2. Training: How pre-service training is provided to the CHW to prepare for his/her role and

ensure s/he has the necessary skills to provide safe and quality care; and, how ongoing

training is provided to reinforce initial training, teach CHWs new skills, and to help ensure

quality.

3. Accreditation: How health knowledge and competencies are assessed and certified

prior to practicing and recertified at regular intervals while practicing.

4. Equipment and Supplies: How the requisite equipment and supplies are made

available when needed to deliver expected services.

5. Supervision: How supportive supervision is carried out such that regular skill

development, problem solving, performance review, and data auditing are provided.

6. Incentives: How a balanced incentive package reflecting job expectations, including

financial compensation in the form of a salary, and non-financial incentives, is provided.

7. Community Involvement: How a community supports the creation and maintenance of

the CHW program.

8. Opportunity for Advancement: How CHWs are provided career pathways.

9. Data: How community-level data flow to the health system and back to the community

and how they are used for quality improvement.

10. Linkages to the National Health System: The extent to which the Ministry of Health

has policies in place that integrate and include CHWs in health system planning and

budgeting and provides logistical support to sustain district, regional and/or national

CHW programs.

5

Program Functionality Matrix Process

To utilize the CHW AIM tool in assessing CHW programs, a detailed facilitation process has been described

previously [13]. We here provide a summary of the process and recommend implementers and policymakers

utilizing the CHW AIM tool consult the full facilitator’s guide for further detail (http://www.who.int/

workforcealliance/knowledge/toolkit/54/en/).

Facilitation: Although participatory in nature, the process should be led by a trained facilitator.

Participants: The assessment is typically carried out during a workshop with multiple stakeholders

knowledgeable about how the program is managed or supported and the regions within which it functions.

Participants are encouraged to include field managers, district managers, national-level community health

policymakers, CHWs, CHW supervisors, and community members/patients.

Approach: The assessment approach allows host governments to quickly and efficiently map and assess

programs using a rating scale based on best practices. Ideally, the process encourages discussions on actual

versus intended implementation of community-based programs (i.e. fidelity).

Limitations: The methodology relies on secondary evidence and self-reports for assessment and so can only

provide an indication of the program’s potential based on current best evidence and practitioner expertise. It is

not an outcome assessment.

Scoring of Programmatic Components

Each of the 10 components in the CHW Program Functionality Matrix is subdivided into four levels of functionality,

ranging from non-functional (level 1) to highly functional as defined by suggested best practices (level 4).

Stakeholders should identify where their programs fall within that range.

1 Non functional 2 Partially Functional 3 Functional 4 Highly Functional

X

6

1

Role & Recruitment

How the community, CHW, and health system design and achieve clarity on the CHW role and from where the

CHW is identified and selected.

7

• No formal CHW role is defined or

documented (no policies in place).

• Attitudes, expertise, and availability

deemed essential for the job are not

clearly delineated prior to recruitment.

• CHW not from community.

• The community plays no role in

recruitment.

1 Non functional

• CHW and community do not always

agree on role/ expectations.

• Attitudes, expertise, and availability

deemed essential for the job are not

clearly delineated prior to

recruitment.

• CHW is recruited from community.

• The community is involved in

screening of candidates.

2 Partially Functional

• CHW:population ratio reflects CHW role

expectation, population density,

geographic constraints, and travel

requirements.

• CHW role is clearly defined and

documented. General agreement on

role among CHW, community, and

health system.

• Attitudes, expertise, and availability

deemed essential for the job are clearly

delineated prior to recruitment and

linked to specific interview questions.

• CHW is recruited from the community

and the community is consulted on the

final selection, or if due to special

circumstances the CHW must be

recruited from outside the community,

the community is consulted on the final

selection.

3 Functional

• CHW role is clearly defined and

documented. Agreement on role among

CHW, community, and health system.

• CHW:population ratio reflects CHW role

expectation, population density,

geographic constraints, and travel

requirements.

• Recruitment methods and selection

criteria designed to maximize women’s

participation in the workforce and

overcome gender inequities.

• CHW is recruited from community with

community participation, or if due to

special circumstance the CHW is

recruited from outside the community,

the community participates in and

agrees with the recruitment process and

is consulted on the final selection.

• Attitudes, expertise, and availability

deemed essential for the job are clearly

delineated prior to recruitment and

linked to specific interview questions/

competency demonstrations (e.g.

literacy test).

• Role of CHWs includes proactively

searching for patients door-to-door, care

for patients in their homes, and provide

training to families on how to identify

danger signs.

• Train-then-select: recruit more CHWs to

the first module of pre-service training

than are ultimately needed and select

the best performer from each

community to continue training and

ultimately serve as that community’s

CHW.

4 Highly Functional

2

Training

How pre-service training is provided to the CHW to prepare for his/her role and ensure s/he has the necessary skills to provide safe and quality care;

and, how ongoing training is provided to reinforce initial training, teach CHWs new skills, and to help ensure quality.

8

• No or minimal initial training is

provided.

• Minimal initial training is provided (e.g.,

one workshop) that is not based on

global guidelines.

• No participation from community or

government health service during initial

training.

• No ongoing training is provided.

• Some coaching is provided in

occasional, ad hoc visits by supervisors.

1 Non functional

• Initial training is provided to all

CHWs within six months of

recruitment, but training does not

meet global guidelines.

• No participation from community or

government health service during

initial training.

• No ongoing training is provided.

• Refresher training is provided but is

irregular or occurs less frequently

than every 12 months.

• Partner organizations/NGOs provide

ad hoc workshops on specific

vertical health topics. These are not

integrated into the national plan.

2 Partially Functional

• Initial training meeting global

guidelines is provided to all CHWs

within six months of recruitment.

• Little participation from community or

government health service during initial

training.

• Refresher training is provided for all

CHWs at least annually.

• Any workshops on vertical health topics

are integrated into the national plan for

ongoing training.

3 Functional

• Initial training meeting global guidelines

is provided to all CHWs within six months

of recruitment.

• CHW training includes practicum time in

government health facilities and in the

community.

• Continuous capacity development (e.g.

fortnightly or quarterly through

mentorship or on-the-job training) is

provided to reinforce initial training,

teach CHWs new skills, and to help

ensure quality.

4 Highly Functional

3

Accreditation

How health knowledge and competencies are assessed and certified prior to practicing and recertified at regular intervals

while practicing.

9

• Health knowledge and competencies

are not tested prior to practicing.

1 Non functional

• CHWs do pre-/post-tests but no

minimum standard of achievement

has been set.

2 Partially Functional

• Health knowledge and competencies

are tested and CHWs must meet a

minimum standard prior to practicing

• Provisions for CHWs to re-test are in

place.

3 Functional

• Health knowledge and competencies are

tested and CHWs must meet a minimum

standard prior to practicing.

• Provisions for CHWs to re-test are in

place in the case of failure.

• CHWs are accredited by a national body

based on clear documented standards.

4 Highly Functional

4

Equipment and Supplies

How the requisite equipment and supplies are made available to CHWs when needed to deliver expected services.

10

• No or incomplete equipment, supplies,

and job aids provided.

• No regular process for ordering

supplies exists; CHWs order when they

run out.

1 Non functional

• Equipment, supplies, and job aids

are provided, though stockouts of

essential supplies occur regularly

and last more than one month.

• Supplies are ordered on a regular

basis, though procurement can be

irregular.

2 Partially Functional

• Equipment, supplies, and job aids are

provided. Stockouts are rare.

• Supplies are ordered and available for

resupply on a regular basis.

• Supplies are checked or updated

regularly to verify expiration dates,

quality, and inventory.

3 Functional

• All necessary supplies, including job aids,

are available with no substantial

stockout periods.

• Supplies are ordered and available for

resupply on a regular basis and buffer

stock is available. At all levels, a standard

tool is used for supply forecasting (e.g.

UNICEF/MSH’s Community Health

Planning and Costing Tool) [23].

• Supplies are checked and updated

regularly to verify expiration dates,

quality, and inventory.

• CHW inventory is monitored, whether

through manual or digital systems.

4 Highly Functional

out such that regular skill development, problem solving, performance review, and data

5

Supervision

How supportive supervision is carried

auditing are provided.

11

• No supervision or regular evaluation

occurs outside of occasional visits to

CHWs by nurses or supervisors when

possible (once a year or less

frequently).

1 Non functional

• Supervision visits or group meetings

at the health facility occur between

2 and 3 times per year for data

collection.

• Supervisors are not assigned to

CHWs or communities or are

unknown to CHWs and

communities.

• Supervisors are not trained.

• No individual performance support

is offered (e.g. problem-solving,

coaching).

2 Partially Functional

• A dedicated supervisor conducts

supervision visits at least every 3

months that include reviewing reports

and providing problem- solving support

to the CHW.

• Supervisors are trained and have basic

supervision tools (checklists) to aid

them.

• The supervisor provides summary

statistics of CHW performance to CHW

to identify areas for improved service

delivery.

• The supervisor does not consistently

meet with the community and does not

make home visits with the CHW or

provide on-the-job skill building.

3 Functional

• A dedicated supervisor conducts

monthly supervision visits that include

reviewing reports and providing

problem- solving support to the CHW.

• Supervisors are trained, have the

technical skills to do service delivery

observations, and have basic supervision

tools checklists to aid them.

• The supervisor provides summary

statistics of CHW performance (e.g.

number of home visits, number of

protocol errors) to CHW to identify areas

for improved service delivery.

• The supervisor directly observes CHW

practice with patients and provides

targeted feedback a"er patient

encounter on areas for continued

improvement.

• The supervisor audits data/assesses

patient experience (without the CHW

present).

• Program directors have considered how

else supervisors can serve CHWs and the

community (e.g., restocking supplies,

referral support, higher level care, etc.)

and have implemented services as

applicable.

4 Highly Functional

6

Incentives

How a balanced incentive package reflecting job expectations, including financial compensation in the form of a salary and

non-financial incentives, is provided.

12

• No financial or non- financial incentives

are provided.

• Recognition from community is

considered a reward and the CHW is

sometimes given small tokens.

1 Non functional

• Some limited financial incentives

are provided—such as transport to

training, stipends below minimum

wage—but there is no salary or

bonus. Or the majority of salary

payments are not paid on time.

• Some non-financial incentives are

offered.

2 Partially Functional

• Full-time CHWs are compensated

financially at a competitive rate relative

to the respective market (at least

minimum wage, if not more

competitive). Salaries are paid on time

the vast majority of the time.

• Incentives are balanced, with both

financial and non-financial incentives

provided, commensurate with

expectations of CHW role (e.g., number

and duration of visits to patients,

workload, and services provided).

• The possibility for negative unintended

consequences has been examined prior

to integrating performance incentives

for specific tasks. They have been put in

place only if the possibility that CHWs

devote less attention to non-

incentivized tasks can be prevented.

•

3 Functional

• Full-time CHWs are compensated

financially at a competitive rate relative

to the respective market (at least

minimum wage, if not more

competitive), and salaries are

consistently paid on-time.

• Incentives are balanced, with both

financial and non-financial incentives

provided, and are commensurate with

expectations of CHW role, role (e.g.,

number and duration of visits to

patients, workload, and services

provided).

• The possibility for negative unintended

consequences has been examined prior

to integrating performance incentives for

specific tasks. They have been put in

place only if the possibility that CHWs

devote less attention to non-incentivized

tasks can be prevented.

• Health workers receive employee

benefits (e.g. housing, vacation etc.).

4 Highly Functional

7

Community Involvement

How a community supports the creation and maintenance of the CHW program.

13

• Community plays no role in ongoing

support to CHWs.

1 Non functional

• Community is sometimes involved

(campaigns, education) with the

CHW and some people in the

community recognize the CHW as a

resource.

• Community is only represented by

“elites” and leaves out key

demographic groups (i.e. women,

minorities, youth, people with

disabilities, etc.).

2 Partially Functional

• Community plays significant role in

supporting the CHW (i.e. discusses role

or objectives, provides regular

feedback).

• CHW is widely recognized and

appreciated by the community for

providing service to the community.

• CHW engages existing community

structures (e.g. health committees,

community meetings).

• Community has little or no interaction

with CHW supervisor.

• Community is not engaged in planning

CHW programs or evaluating the health

system.

3 Functional

• Community plays significant role in

supporting the CHW (i.e. discusses role

or objectives, provides regular feedback)

and helps to establish the CHW as a

leader in community.

• CHW is widely recognized and

appreciated for providing service to

community.

• Community leaders have ongoing

dialogue with CHW regarding health

issues using data gathered by the CHW.

• CHW engages existing multisectoral

community structures (e.g. health

committees, community meetings).

• Community interacts with supervisor

during visits to provide feedback and

solve problems.

• A broad cross-section of the community

plays a role in planning the CHW

program and providing feedback to the

health system.

4 Highly Functional

8

Opportunity for Advancement

How CHWs are provided career pathways.

14

• No opportunities for advancement

offered.

1 Non functional

• Advancement opportunities are

sometimes offered to CHWs who

have been in the program for a

specific length of time.

• Advancement is not related to

performance or achievement.

2 Partially Functional

• Advancement is sometimes offered to

CHWs who have been in the program for

a specific length of time.

• Limited training opportunities are

offered to CHWs to learn new skills to

advance roles.

• Advancement is intended to reward

good performance or achievement,

although evaluation is not always

consistent, clear or transparent.

3 Functional

• Advancement is offered to CHWs who

perform well and who express an interest

in advancement if the opportunity exists.

• Training opportunities are offered to

CHWs to learn new skills to advance their

roles and CHWs are aware of them.

• Advancement is intended to reward good

performance or achievement and is

based on a fair evaluation; conversely,

mechanisms are in place for the release

of a poorly performing CHW from their

duties.

4 Highly Functional

9

Data

How community-level data flow to the health system and back to the community and how they are

used for quality improvement

15

• No defined process for documentation

or information management is in place.

• Information is sometimes collected

from CHWs (e.g. annually).

1 Non functional

• Some CHWs document their visits in

notebooks which they take with

them to the facility for review, but a

standardized record format does not

exist.

• CHWs do not have discussions with

supervisors regarding data

collected.

• CHWs/communities do not receive

analyzed data and no effort to use

data in problem solving in the

community is made.

2 Partially Functional

• CHWs document their visits and provide

data in a standardized format.

• Supervisors monitor quality of data,

discuss them with CHWs, and provide.

• Data is reported to public-sector

monitoring and evaluation systems.

• CHWs/communities work with

supervisor to use data in problem

solving at the community level.

3 Functional

• CHWs document their visits consistently

in a standardized format.

• Supervisors monitor quality of data,

discuss data with CHWs, and provide

help when needed.

• Data is reported to public-sector

monitoring and evaluation systems.

• CHWs/communities work with supervisor

to use data in problem solving at the

community level.

• Supervisors use data to provide feedback

on CHW performance and inform

programmatic improvement.

• Digital technologies are employed to

make data systems more efficient,

useable, or scalable and/or leverage data

to improve the quality, speed, or equity

of services.

4 Highly Functional

10

Linkages to Health System

The extent to which the Ministry of Health has policies in place that integrate and include CHWs in health system planning

and budgeting and provides logistical support to sustain CHW programs at district, regional and national levels.

16

• Links to health system are weak or non-

existent; CHW program works in

isolation from health system.

• No referral system in place.

• User fees.

1 Non functional

• CHWs are recognized as helpful in

communities but their role is not

formalized within the health sector.

• CHWs that exist are fully supported

by external funding.

• CHW and community know where

referral facility is but have no formal

referral process, logistics, or forms.

• Minimal user fees for commodities

only.

2 Partially Functional

• CHWs are recognized as part of the

formal health system (policies are in

place that define their roles, tasks,

relationship to health system).

• The national health budget has

appropriate provisions for CHWs (e.g.

salary, equipment, supervision, etc).

• CHW and community know where

referral facility is and typically have the

means to transport patients.

• Patient is referred with a form and

informally tracked by CHW (checking in

with family, follow-up visit), but

information does not flow back to CHW

from referral site.

• User fees for service provision are not

charged.

3 Functional

• CHWs are recognized as part of the

formal health system (policies are in

place that define their roles, tasks,

relationship to health system).

• The national health budget has

appropriate provisions for CHWs (e.g.

salary, equipment, supervision, etc).

• Health system accompanies CHW

deployment with investments to

increase the capacity, accessibility, and

quality of the primary care facilities and

providers to which CHWs link.

• CHWs always have means for transport

and have a functional logistics plan for

emergencies (transport, funds).

• Patient is referred with a standardized

form and information flows back to CHW

with a returned referral form.

• Point-of-care user fees are not charged

for services or for care commodities.

• There is multisectoral engagement (e.g.

Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Public

Service, Ministry of Education, civil

society) in the design, implementation

and management of the CHW program.

4 Highly Functional

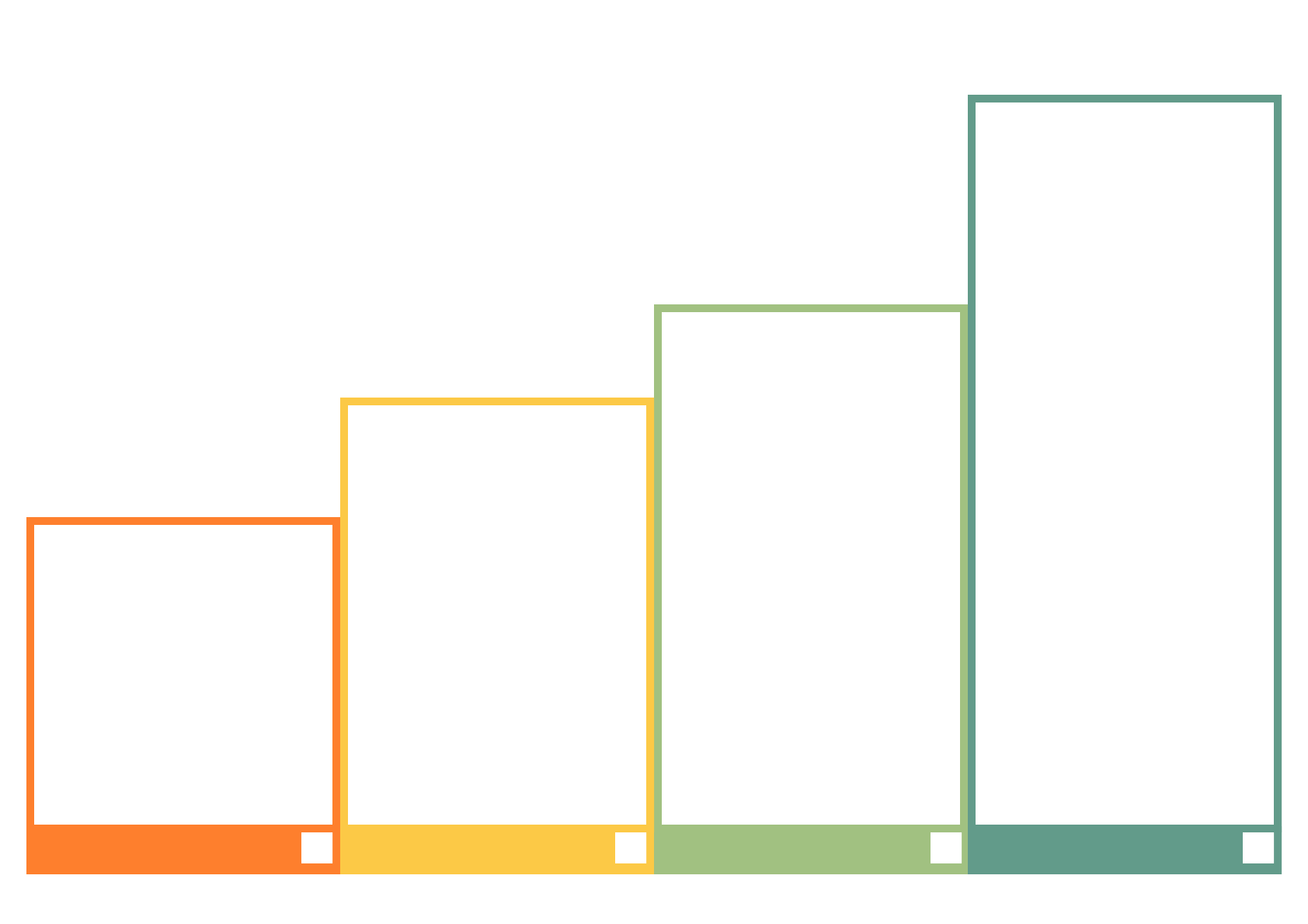

Score overview

1. Non

Functional

2. Partially

Functional

3. Functional

4. Highly

Functional

1. Role & Recruitment

2. Training

3. Accreditation

4. Equipment & Supplies

5. Supervision

6. Incentives

7. Community Involvement

8. Opportunity for

Advancement

9. Data

10. Linkages to the

National Health System

17

APPENDIX

Search strategy

Pubmed:

((("Community health agent” or "Community Health Aides” or

"Community health promoter" or "Community mobilizer” or "Community

drug distributor” or “community health worker” or "Village health

worker”[Title/Abstract])) OR ("Rural Health Worker” or "Lay Health

Worker” or "Lady health worker” or “nutrition worker” or “frontline health

worker” or "Barangay health worker” or “basic health worker” or "Auxiliary

health worker” or “health extension worker” or “community health

volunteer” or “village health volunteer"[Title/Abstract])) OR

(accompanier* OR accompagnateur* OR activista* OR animatrice* OR

brigadista* OR kader* OR promotora* OR monitora* OR sevika* OR fhw*

OR chw* OR lhw* OR vhw* OR chv* OR "shastho shebika" OR "shasto

karmis" OR anganwadi* OR "barefoot doctor" OR "agente comunitario de

salud" OR "agente communitario de saude"[Title/Abstract]))

Keywords for other databases:

(community health worker) OR (CHW) AND (tool) OR (toolkit) OR (manual) OR

(technical) OR (guide) OR (strategy) OR (handbook)

Databases/Grey Literature Repositories

1. CHW Central

2. CoreGroup

3. PubMed

4. USAID

5. World Health Organization

6. Rural Health Information Hub

7. Frontline Health Workers Coalition

8. One Million Community Health Workers Campaign

9. mPowering Frontline Health Workers

10. Community Case Management Central

11. Global Health Workforce Alliance (WHO)

12. Clinton Foundation

References

1. Daelmans, B., et al., Integrated Community Case Management of

Childhood Illness: What have We Learned? The American journal of

tropical medicine and hygiene, 2016. 94(3): p. 571-573.

2. UNICEF. A Decade of Tracking Progress for Maternal, Newborn and Child

Survival, The 2015 Report. 2015 October 10, 2018]; Available from: http://

countdown2030.org/2015/2015-final-report.

3. Scott, K., et al., What do we know about community-based health worker

programs? A systematic review of existing reviews on community health

workers. Hum Resour Health, 2018. 16(1): p. 39.

4. Lewin, S., et al., Lay health workers in primary and community health care

for maternal and child health and the management of infectious

diseases. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2010(3).

5. Amouzou, A., et al., Effects of the integrated Community Case

Management of Childhood Illness Strategy on Child Mortality in Ethiopia:

A Cluster Randomized Trial. American Journal of Tropical Medicine &

Hygiene, 2016. 94(3): p. 596-604.

6. Amouzou, A., et al., Independent Evaluation of the integrated Community

Case Management of Childhood Illness Strategy in Malawi Using a

National Evaluation Platform Design. American Journal of Tropical

Medicine & Hygiene, 2016. 94(3): p. 574-83.

7. Munos, M., et al., Independent Evaluation of the Rapid Scale-Up Program

to Reduce Under-Five Mortality in Burkina Faso. American Journal of

Tropical Medicine & Hygiene, 2016. 94(3): p. 584-95.

8. Ballard, M. and R. Schwarz, Employing practitioner expertise in optimizing

community healthcare systems. Healthc (Amst), 2018.

9. Bonds, M.H. and M.L. Rich, Integrated health system strengthening can

generate rapid population impacts that can be replicated: lessons from

Rwanda to Madagascar. BMJ Global Health, 2018. 3(5).

10. Luckow, P.W., et al., Implementation research on community health

workers' provision of maternal and child health services in rural Liberia.

Bull World Health Organ, 2017. 95(2): p. 113-120.community health

worker programmes: an abridged WHO guideline. The Lancet Global

Health, 2018. 6(12): p. e1397-e1404.

18

APPENDIX

11. Johnson, A.D., et al., Proactive community case management and child

survival in periurban Mali. BMJ Global Health, 2018. 3(2).

12. Crigler, L., et al. Community Health Worker Assessment and Improvement

Matrix (CHW AIM): A Toolkit for Improving CHW Programs and Services.

USAID Healthcare Improvement Project 2011 October 10, 2018]; Available

from: http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/toolkit/50.pdf.

13. Crigler, L., et al. Community Health Worker Assessment and Improvement

Matrix (CHW AIM): A Toolkit for Improving CHW Programs and Services -

Revised Version. USAID Healthcare Improvement Project 2013 October

10, 2018]; Available from: http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/

knowledge/toolkit/CHWAIMToolkit_Revision_Sept13.pdf.

14. Ballard, M. and P. Montgomery, Systematic review of interventions for

improving the performance of community health workers in low-income

and middle-income countries. BMJ Open, 2017. 7(e014216).

15. Kok, M.C., et al., Which intervention design factors influence performance

of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries? A

systematic review. Health Policy and Planning, 2015. 30(9): p. 1207-27.

16. Kangovi, S. and D.A. Asch. The Community Health Worker Boom. 2018

October 10, 2018]; NEJM Catalyst:[Available from: https://

catalyst.nejm.org/community-health-workers-boom/.

17. Black, R.E., et al., Comprehensive review of the evidence regarding the

effectiveness of community-based primary health care in improving

maternal, neonatal and child health: 8. summary and recommendations

of the Expert Panel. J Glob Health, 2017. 7(1): p. 010908.

18. Dahn, B., et al., Strengthening primary health care through community

health workers: Investment case and financing recommendations. 2015,

[Unpublished] 2015 Jul. p. [66] p.

19. Naimoli, J.F., et al., A Community Health Worker "logic model": towards a

theory of enhanced performance in low- and middle-income countries.

Human resources for health, 2014. 12: p. 56.

20. Ballard, M., et al. Practitioner Expertise to Optimize Community Health

Systems: Harnessing Operational Insight. 2017 October 10, 2018];

Available from: https://www.chwimpact.org/. doi:10.13140/RG.

2.2.35507.94247.

21. Palazuelos, D., et al., 5-SPICE: the application of an original framework for

community health worker program design, quality improvement and

research agenda setting. Global Health Action, 2013. 6: p. 19658.

22. Crigler, L., et al., Developing and strengthening community health worker

programs at scale. A reference guide for program managers and policy

makers. Dra", USAID Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program

(MCHIP), Editor. 2013.

23. MSH/UNICEF. Community Health Planning and Costing Tool. 2016

October 18, 2018]; Available from: https://www.msh.org/resources/

community-health-planning-and-costing-tool.

24. “Cometto, G., et al., Health policy and system support to optimise

community health worker programmes: an abridged WHO guideline. The

Lancet Global Health, 2018. 6(12): p. e1397-e1404.

25. WHO (2018) WHO guideline on health policy and system support to

optimize community-based health worker programmes. http://

www.who.int/hrh/community/en/

19