INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL OF NURSES

GUIDELINES

ON ADVANCED

PRACTICE NURSING

2020

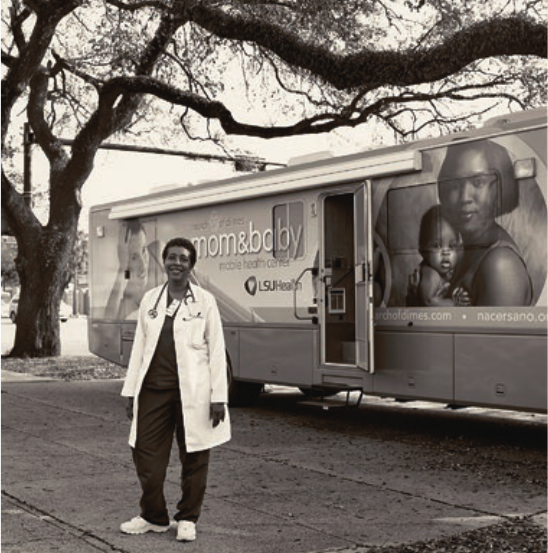

Cover photo: The Twin Bridges Nurse Practitioner

All rights, including translation into other languages, reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in print,

by photostatic means or in any other manner, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or sold

without the express written permission of the International Council of Nurses. Short excerpts (under 300 words)

may be reproduced without authorisation, on condition that the source is indicated.

Copyright © 2020 by ICN - International Council of Nurses,

3, place Jean-Marteau, 1201 Geneva, Switzerland

ISBN: 978-92-95099-71-5

INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL OF NURSES

GUIDELINES

ON ADVANCED

PRACTICE NURSING

2020

2

Mary Wambui Mwaniki

2

3

AUTHORS

Lead Author

Madrean Schober, PhD, MSN, ANP, FAANP

President, Schober Global Healthcare Consulting

International Healthcare Consultants

New York, NY, USA

Contributing Authors

Daniela Lehwaldt, PhD, MSc, PGDipED, BNS

Deputy Chair, ICN NP/APN Network

Assistant Professor and International Liaison

School of Nursing and Human Sciences

Dublin City University, Republic of Ireland

Melanie Rogers, PhD

Chair, ICN NP/APN Network

Advanced Nurse Practitioner

University Teaching Fellow

University of Hudderseld, U.K.

Mary Steinke, DNP, APRN-BC, FNP-C

ICN NP/APN Core Steering Group

Liaison, Practice Subgroup

Director Family Nurse Practitioner Program

Indiana University-Kokomo, Indiana, USA

Sue Turale, RN, DEd, FACN, FACMHN

Editor/Consultant

International Council of Nurses

Geneva, Switzerland

Visiting Professor, Chiang Mai University,

Chiang Mai, Thailand

Joyce Pulcini, PhD, PNP-BC, FAAN, FAANP

Professor, George Washington University

School of Nursing

Washington, DC, USA

Josette Roussel, MSc, MEd, RN

Program Lead, Nursing Practice and Policy

Programs and Policy

Canadian Nurses Association

Ottawa, Canada

David Stewart, RN, BN, MHM

Associate Director, Nursing and Health Policy

International Council of Nurses

Geneva, Switzerland

4 5

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

ICN would like to thank the following people who provided a preliminary review of the guidelines:

•

Fadwa Affara, Consultant, Edinburgh, Scotland

•

Fariba Al Darazi, Prior Regional Director of Nursing, WHO, Regional Ofce of the Eastern Mediterranean

Region, Bahrain

•

Majid Al-Maqbali, Directorate of Nursing, Ministry of Health, Oman

•

Michal Boyd, Nurse Practitioner/Professor, University of Auckland, New Zealand

•

Lenora Brace, President, Nurse Practitioner Association of Canada

•

Karen Brennan, Past President, Irish Association of Nurse Practitioners

•

Denise Bryant-Lukosius, Professor, McMaster University, Canadian Centre for APN Research

•

Jenny Carryer, Professor, Massey University, New Zealand

•

Sylvia Cassiani, Regional Advisor for Nursing, Pan American Health Organization

•

Irma H. de Hoop, Dutch Association of Nurse Practitioners, Netherlands

•

Christine Dufeld, Professor, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia

•

Pilar Espinoza, Director, Postgraduate, research and international affairs at the health care sciences faculty

of the San Sebastián University, Chile

•

Lisbeth Fagerstrom, Professor, University College of Southeast Norway

•

Glenn Gardner, Emeritus Professor, Queensland University of Technology, Australia

•

Nelouise Geyer, CEO, Nursing Education Association, Pretoria, South Africa

•

Susan Hassmiller, Senior Advisor for Nursing, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, USA

•

Heather Henry-McGrath, President, Jamaica Association of Nurse Practitioners, International

Ambassador-American Association of Nurse Practitioners

•

Simone Inkrot, Sabrina Pelz, Anne Schmitt, Christoph von Dach, APN/ANP Deutches Netzwerk G.E.V.,

Germany and Switzerland

•

Anna Jones, Senior Lecturer, School of Healthcare Sciences, College of Biomedical and Life Sciences,

Cardiff University, Wales

•

Elke Keinhath, Advanced Practice Nurse, APN/ANP Deutches Netzwerk G.E.V., Germany

•

Mabedi Kgositau, International Ambassador-American Association of Nurse Practitioners,

University of Botswana

•

Sue Kim, Professor, College of Nursing Yonsei University, South Korea

•

Karen Koh, Advanced Practice Nurse, National University Hospital, Singapore Nursing Board

•

Katrina Maclaine, Associate Professor, London South Bank University

•

Vanessa Maderal, Adjunct Professor, University of the Philippines

•

Donna McConnell, Lecturer in Nursing, Ulster University, Northern Ireland

•

Evelyn McElhinney, Senior lecturer, Programme Lead MSc Nursing: Advancing Professional Practice,

Glasgow Caledonian University, Scotland

•

Arwa Oweis, Regional Advisor for Nursing, WHO, Regional Ofce of the Eastern Mediterranean Region,

Cairo, Egypt

•

Jeroen Peters, Program Director, Nimigen University, Netherlands

•

Andrew Scanlon, Associate Professor, Montclair University, Australia

•

Bongi Sibanda, Advanced Nurse Practitioner, Anglophone Africa APN Coalition Project, Zimbabwe

•

Anna Suutaria, Head of International Affairs, Finnish Nurses’ Association

•

Peter Ullmann, Chair, APN/ANP Deutsches Netzwerk G.E.V., Germany

•

Zhou Wentao, Director, MScN Programme, National University of Singapore

•

Kathy Wheeler, Co-chair International Committee, American Association of Nurse Practitioners

•

Frances Wong, Professor, Hong Kong Polytechnic University

GUIDELINES ON ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING 2020

4 5

TABLE OF CONTENTS

List of Tables/Figures .............................................................................................................................................6

Glossary of terms ...................................................................................................................................................6

Foreword .................................................................................................................................................................7

Purpose of the ICN APN Guidelines .....................................................................................................................8

Abstract ...................................................................................................................................................................8

Chapter One: Advanced Practice Nursing ...........................................................................................................9

1.1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................................................9

1.2 Assumptions about Advanced Practice Nursing ..................................................................................9

1.3 Advanced Practice Nursing Characteristics .......................................................................................10

1.4 Country Issues that Shape Development of Advanced Practice Nursing ....................................... 11

Chapter Two: The Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) ............................................................................................12

2.1 ICN Position on the Clinical Nurse Specialist .....................................................................................12

2.2 Background of the Clinical Nurse Specialist ......................................................................................12

2.3 Description of the Clinical Nurse Specialist........................................................................................13

2.4 Clinical Nurse Specialist Scope of Practice ........................................................................................13

2.5 Education for the Clinical Nurse Specialist ........................................................................................14

2.6 Establishing a Professional Standard for the Clinical Nurse Specialist ..........................................14

2.7 Clinical Nurse Specialists’ Contributions to Healthcare Services ....................................................15

2.8 Differentiating a Specialised Nurse and a Clinical Nurse Specialist ................................................15

Chapter Three: The Nurse Practitioner ..............................................................................................................18

3.1 ICN Position on the Nurse Practitioner ................................................................................................18

3.2 Background of the Nurse Practitioner .................................................................................................18

3.3 Description of the Nurse Practitioner .................................................................................................18

3.4 Nurse Practitioner Scope of Practice...................................................................................................18

3.5 Nurse Practitioner Education ...............................................................................................................20

3.6 Establishing a Professional Standard for the Nurse Practitioner .....................................................21

3.7 Nurse Practitioner Contributions to Healthcare Services..................................................................21

Chapter Four: Distinguishing the Clinical Nurse Specialist and the Nurse Practitioner ...............................22

4.1 ICN Position on the Clarication of Advanced Nursing Designations ............................................23

References ............................................................................................................................................................27

Appendices ...........................................................................................................................................................33

Appendix 1: Credentialing Terminology ......................................................................................................33

Appendix 2: The International Context and Country Examples of the CNS .............................................33

Appendix 3: The International Context and Country Examples of the NP ................................................35

Appendix 4: Country exemplars of adaptations or variations of CNS and NP .........................................38

GUIDELINES ON ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING 2020

6

LIST OF TABLES/FIGURES

Table 1: Characteristics delineating Clinical Nurse Specialist practice

Table 2: Differentiating a Specialised Nurse and a Clinical Nurse Specialist

Table 3: Characteristics of Clinical Nurse Specialists and Nurse Practitioners

Table 4: Similarities between Clinical Nurse Specialists and Nurse Practitioners

Table 5: Differentiating the Clinical Nurse Specialist and the Nurse Practitioner

Figure 1: Progression from Generalist Nurse to Clinical Nurse Specialist

Figure 2: Distinction between Clinical Nurse Specialist and Nurse Practitioner

GLOSSARY OF TERMS

Advanced Nursing Practice (ANP)

Advanced Nursing Practice is a eld of nursing that

extends and expands the boundaries of nursing’s

scope of practice, contributes to nursing knowledge

and promotes advancement of the profession (RNABC

Policy Statement, 2001). ANP is ‘characterised by the

integration and application of a broad range of theoret-

ical and evidence-based knowledge that occurs as part

of graduate nursing education’ (ANA, 2010 as cited in

Hamric & Tracy, 2019, p. 63).

Advanced Practice Nurse (APN)

An Advanced Practice Nurse (APN) is a generalist or

specialised nurse who has acquired, through additional

graduate education (minimum of a master’s degree),

the expert knowledge base, complex decision-making

skills and clinical competencies for Advanced Nursing

Practice, the characteristics of which are shaped by

the context in which they are credentialed to practice

(adapted from ICN, 2008). The two most commonly

identied APN roles are CNS and NP.

Advanced Practice Nursing (APN)

Advanced Practice Nursing, as referred to in this paper,

is viewed as advanced nursing interventions that inu-

ence clinical healthcare outcomes for individuals,

fam ilies and diverse populations. Advanced Practice

Nursing is based on graduate education and prepar-

ation along with the specication of central criteria and

core competencies for practice (AACN, 2004, 2006,

2015; Hamric & Tracy, 2019).

Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN)

APRN, as used in the USA, is the title given to a nurse

who has met education and certication requirements

and obtained a license to practice as an APRN in one

of four APRN roles: certied registered nurse anesthe-

tist (CRNA), certied nurse-midwife (CNM), Clinical

Nurse Specialist (CNS), and certied Nurse Practitioner

(CNP) (APRN Consensus Model, 2008).

Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS)

A Clinical Nurse Specialist is an Advanced Practice

Nurse who provides expert clinical advice and care

based on established diagnoses in specialised clin-

ic al elds of practice along with a systems approach in

practicing as a member of the healthcare team.

Nurse Practitioner (NP)

A Nurse Practitioner is an Advanced Practice Nurse

who integrates clinical skills associated with nursing

and medicine in order to assess, diagnose and man-

age patients in primary healthcare (PHC) settings and

acute care populations as well as ongoing care for

popu lations with chronic illness.

GUIDELINES ON ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING 2020

6 7

FOREWORD

2020 has been named The International Year of the

Nurse and Midwife by the World Health Organization. It

celebrates both the professionals who provide a broad

range of essential health services to people every-

where as well as the bicentenary of the birth of Florence

Nightingale. However, the International Council of

Nurses (ICN) recognises that this year needs to be

more than just a celebration. It needs to be a time of

action and commitment by governments, health sys-

tems and the public to support the capacity, capability

and empowerment of the nursing profession to meet the

growing demands and health needs of individuals and

communities. Without the nursing profession, millions

of people around the world will not be able to access

quality, safe and affordable healthcare services. As the

largest group of healthcare workers providing the vast

majority of care, particularly in the primary care setting,

it is not surprising that the nursing workforce investment

can yield signicant improvement in patient outcomes.

Throughout history, we can see the continual evolution

of the nursing profession in order to address the health,

societal and person-centred care challenges.

It is for this reason, that as the global voice of nursing,

ICN has been calling for investment in nursing, and in

particular APN, to address global health challenges. As

a Commissioner on the WHO High Level Commission

on Noncommunicable Diseases (NCDs), the ICN

President witnessed the global community wrestle with

solutions to address the need to reduce mortality from

NCDs by 30% by 2030. What became clear was that

the status quo cannot continue and that governments

need to reorient their health systems and support

the health workforce, particularly APNs, to effectively

respond to promotion, prevention and management

of disease. This is echoed in the Astana Declaration

with the visionary pursuit of achieving Health for All

through Primary Health Care. The foundation for this

is nurses working to their full scope of practice. We

boldly declare, that APNs are an effective and efcient

resource to address the challenges of accessible, safe

and affordable health care.

This is clearly evident in Advanced Practice Nursing

(APN). Whilst this appears to be a relatively recent con-

cept, distinct patterns can be seen in the transition of

specialty practice into Advanced Practice Nursing over

the last 100 years. (Hanson & Hamric 2003)

Over this time there has been growing demand for APN

globally; however, many countries are in different stages

of development of these roles as part of the nursing

workforce. In addition, many APN positions have devel-

oped on an ad-hoc basis with varying responsibilities,

roles and nomenclature. The scope of practice is often

diverse and heterogenous across global regions. Often

pathways to entry and practice boundaries can be

blurred, poorly understood and sometimes contested.

This has led to confusion amongst policy makers,

health professionals and the public at large.

To seize the richness and opportunities afforded by

Advanced Practice Nursing, it is important that the pro-

fession provide clear guidance and direction. ICN has

been a leader in the development of the profession-

alisation of nursing since its very beginning in 1899.

It has provided guidance on a range of topics related

to nursing including the most widely used denition of

APN to date.

ICN is seeking to build on this work through the release

of these new guidelines on Advanced Practice Nursing.

Undertaken with the leadership support of the ICN

APN/NP Network, these guidelines have undergone an

extremely rigorous and robust global consultation pro-

cess. They aim to support the current and future devel-

opment of APN across countries in order to improve the

quality of service that our profession offers to individu-

als and communities.

Our hope is that through the development of these

guidelines, some of the barriers and walls that have hin-

dered the nursing profession can be torn down. These

guidelines will hopefully support the profession, enable

a clearer understanding and assist in the continual evo-

lution of APN. People around the world have the right

to quality, safe and affordable healthcare. Advanced

Practice Nurses are one of the solutions to making this

happen.

Annette Kennedy Howard Catton

ICN President ICN Chief Executive Ofcer

8

GUIDELINES ON ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING 2020

8

Mary Wambui Mwaniki

PURPOSE OF THE ICN APN GUIDELINES

The purpose of these guidelines is to facilitate a com-

mon understanding of Advanced Practice Nursing and

the Advanced Practice Nurse (APN) for the public,

governments, healthcare professionals, policy makers,

educators and the nursing profession. It is envisioned

that the work will support these stakeholders to develop

policies, frameworks and strategies supportive of an

Advanced Practice Nursing initiative. Those countries

that have implemented the APN role can review their

current state of Advanced Practice Nursing against

these recommended guidelines. This will support con-

sistency and clarity of Advanced Practice Nursing inter-

nationally and enable further development of APN roles

to meet the healthcare needs of individuals and com-

munities. This work is also important to the progres-

sion of research in this eld of nursing both within and

across countries.

It is recognised that the identication and context of

Advanced Practice Nursing varies in different parts of

the world. It is also acknowledged that the profession

is dynamic with changes to education, regulation and

nursing practice as it seeks to respond to healthcare

needs and changes to provision of healthcare services.

However, these guidelines provide common principles

and practical examples of international best practice.

ABSTRACT

In order to meet changing global population needs and

consumer expectations, healthcare systems worldwide

are under transformation and face restructuring. As

systems adapt and shift their emphasis in response to

the disparate requests for healthcare services, oppor-

tunities emerge for nurses, especially the APN, to meet

these demands and unmet needs (Bryant-Lukosius et

al. 2017; Carryer et al. 2018; Cassiani & Zug 2014;

Cooper & Docherty 2018; Hill et al. 2017; Maier et

al. 2017).

In 2002, the International Council of Nurses (ICN) pro-

vided an ofcial position on Advanced Practice Nursing

(ICN 2008a). Since that time, worldwide development

has increased signicantly and simultaneously this

eld of nursing has matured. ICN felt that a review of

its position was needed to assess the relevance of the

denition and characteristics offered in 2002. This guid-

ance paper denes diverse elements such as assump-

tions and core components of the APN. The attributes

and descriptors presented in this paper are intended

to promote a common vision to continue to enable a

greater understanding by the international nursing and

healthcare communities for the development of roles

commonly identied as Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS)

and Nurse Practitioner (NP).

8

CHAPTER ONE: ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING

98

CHAPTER ONE

ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING

1.1 Introduction

1 In this paper, the emphasis is on the characteristics and professional standard of the CNS. The title of CNS is used to represent the role or level of nursing

as it is a widely identied category of Advanced Practice Nursing worldwide.

2 As per ICN’s denition of a nurse, the nurse is a person who has completed a programme of basic, generalised nursing education and is authorised by the

appropriate regulatory authority to practice nursing in his/her own country. https://www.icn.ch/nursing-policy/nursing-denitions

Advanced Practice Nursing, as discussed in this paper,

refers to enhanced and expanded healthcare ser-

vices and interventions provided by nurses who, in an

advanced capacity, inuence clinical healthcare out-

comes and provide direct healthcare services to indi-

viduals, families and communities (CNA 2019; Hamric

& Tracy 2019). An Advanced Practice Nurse (APN) is

one who has acquired, through additional education,

the expert knowledge base, complex decision-making

skills and clinical competencies for expanded nursing

practice, the characteristics of which are shaped by the

context in which they are credentialed to practice (ICN

2008a). The Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS)

1

and Nurse

Practitioner (NP) are two types of APNs most frequently

identied internationally (APRN 2008; Begley 2010;

Carryer et al 2018; CNA 2019; Finnish Nurses

Association 2016; Maier et al. 2017, Miranda Neto

et al. 2018).

This guidance paper begins by providing overarching

assumptions of Advanced Practice Nursing. In addition,

core elements of the CNS and NP are presented in

Chapters Two and Three, together with ICN’s positions

on these nursing roles. In order to facilitate dialogue to

distinguish two types of APNs (CNSs and NPs), prac-

tice characteristics of the CNS and NP are presented

and differentiated in Chapter 4. Country exemplars pro-

vided in the Appendices depict the diversity of CNS and

NP practice.

1.2 Assumptions about Advanced Practice Nursing

The following assumptions represent the nurse who is

prepared at an advanced educational level and then

achieves recognition as an APN (CNS or NP). These

statements provide a foundation for the APN and a

source for international consideration when trying to

understand Advanced Practice Nursing, regardless of

work setting or focus of practice. All APNs:

•

are practitioners of nursing, providing safe

and competent patient care

•

have their foundation in nursing education

•

have roles or levels of practice which require formal

education beyond the preparation of the generalist

2

nurse (minimum required entry level

is a master’s degree)

•

have roles or levels of practice with increased levels

of competency and capability that are measurable,

beyond that of a generalist nurse

•

have acquired the ability to explain and apply

the theoretical, empirical, ethical, legal, care

giving, and professional development required

for Advanced Practice Nursing

•

have dened APN competencies and standards

which are periodically reviewed for maintaining

currency in practice, and

•

are inuenced by the global, social, political,

economic and technological milieu.

(Adapted from ICN 2008a)

The degree and range of judgement, skill, knowledge,

responsibility, autonomy and accountability broadens

and takes on an additionally extensive range between

the preparation of a generalist nurse and that of the

APN. This added breadth and further in-depth prac-

tice is achieved through experience in clinical practice,

additional education, and a master’s degree or beyond.

However, the core of the APN remains based within the

context of nursing and nursing principles (Adapted from

ICN 2008a).

Results from research conducted in Australia found that

nurses in the eld of Advanced Practice Nursing exhibit

patterns of practice that are different from other nurses

(Gardner et al, 2015). Using an Advanced Practice

Role Delineation tool based on the Strong Model of

Advanced Practice, ndings demonstrate the cap-

acity to clearly delineate and dene Advanced Practice

Nursing (Gardner et al, 2017). The signicance of this

research suggests that, from a healthcare workforce

perspective, it is possible to measure the level of nurs-

ing practice identied as Advanced Practice Nursing

and to more clearly identify these roles and positions.

GUIDELINES ON ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING 2020

10

1.3 Advanced Practice Nursing Characteristics

Role characteristics can be viewed as features that

make Advanced Practice Nursing and the APN rec-

ognisable. Descriptions of the domains of education,

practice, research, leadership and professional regula-

tion provide guidance when making a clear distinction

between advanced versus generalist nursing practice.

While the core of APN practice is based on advanced

nursing education and knowledge, an overlap of expert-

ise may occur with other healthcare professionals. The

breadth and depth of autonomy associated with the

APN often arises within a broader and more extensive

range in community-based services such as primary

healthcare, ambulatory services and out-of- hospital set-

tings. The degree of autonomy may evolve or expand

over time as the concept of Advanced Practice Nursing

gains recognition.

The following sections provide guidelines for identifying

Advanced Practice Nursing:

Educational preparation

•

Educational preparation beyond that of a generalist

or specialised nurse education at a minimum

requirement of a full master’s degree programme

(master’s level modules taken as detached courses

do not meet this requirement). It is acknowledged

that, for some countries, the requirement of a

master’s degree may be an aspirational goal

as they strive to achieve this standard. Transitional

programmes and bridging courses can be dened

to progress to this standard.

•

Formal recognition of educational programmes

preparing nurses specically for Advanced

Practice Nursing (CNS or NP) (e.g. accreditation,

approval or authorisation by governmental

or nongovernmental agencies).

•

A formal system of credentialing linked to dened

educational qualications.

•

Even though some countries require clinical

experience for a nurse to enter an APN education

programme, no evidence was found to support

this requirement.

Nature of practice

•

A designated role or level of nursing that

has its focus on the provision of care, illness

prevention and cure based on direct and indirect

healthcare services at an advanced level,

including rehabilitative care and chronic disease

management. This is beyond the scope of practice

of a generalist or specialised nurse (see Section 2.3

for denitions of direct and indirect care).

•

The capability to manage full episodes of care

and complex healthcare problems including hard

to reach, vulnerable and at-risk populations.

•

The ability to integrate research (evidence informed

practice), education, leadership and clinical

management.

•

Extended and broader range of autonomy (varies

by country context and clinical setting).

•

Case-management (manages own case load

at an advanced level).

•

Advanced assessment, judgement, decision-making

and diagnostic reasoning skills.

•

Recognised advanced clinical competencies,

beyond the competencies of a generalist

or specialised nurse.

•

The ability to provide support and/or consultant

services to other healthcare professionals

emphasising professional collaboration.

•

Plans, coordinates, implements and evaluates

actions to enhance healthcare services

at an advanced level.

•

Recognised rst point of contact for clients

and families (commonly, but not exclusively,

in primary healthcare settings).

Regulatory mechanisms – Country specic

professional regulation and policies underpinning

APN practice:

•

Authority to diagnose

•

Authority to prescribe medications

•

Authority to order diagnostic testing and therapeutic

treatments

•

Authority to refer clients/patients to other services

and/or professionals

•

Authority to admit and discharge clients/patients

to hospital and other services

•

Ofcially recognised title(s) for nurses working

as APNs

•

Legislation to confer and protect the title(s)

(e.g. Clinical Nurse Specialist, Nurse Practitioner)

•

Legislation and policies from an authoritative

entity or some form of regulatory mechanism

explicit to APNs (e.g. certication, credentialing

or authorisation specic to country context)

(Adapted from ICN, 2008a)

The assumptions and characteristics for Advanced

Practice Nursing are viewed as inclusive and exible

to take into consideration variations in healthcare sys-

tems, regulatory mechanisms and nursing education in

individual countries. Over the years, Advanced Practice

Nursing and nursing globally have matured with the APN

seen as a clinical expert, with characteristics of the role

crosscutting other themes that include understanding

and inuencing the issues of governance, policy devel-

opment and clinical leadership (AANP 2015; CNA 2019;

Scottish Government 2008; NCNZ 2017a). Promotion

of leadership competencies and integration of research

knowledge and skills have increasingly become core

elements of education and role development along

with advanced clinical expertise. In the United Kingdom

(UK), all four countries use a four-pillars coordinated

approach encompassing clinical practice, leadership,

education and research. Clinical practice is viewed as

the main pillar to develop when faced with funding and

human resource issues (personal communication K.

Maclaine, March 2019).

10

CHAPTER ONE: ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING

11

1.4 Country Issues that Shape Development of Advanced Practice Nursing

The fundamental level of nursing practice and access

to an adequate level of nursing education that exists

in a country shapes the potential for introducing and

developing Advanced Practice Nursing. Launching an

Advanced Practice Nursing initiative is inuenced by the

professional status of nursing in the country and its ability

to introduce a new role or level of nursing. The prom-

inence and maturity of nursing can be assessed by the

presence of other nursing specialties, levels of nursing

education, policies specic to nurses, extent of nursing

research and nursing leadership (Schober 2016).

It is acknowledged that in countries where generalised

nursing education is progressing and the country con-

text is considering development of a master’s degree

education for Advanced Practice Nursing, that transition

programmes or bridging courses can be developed to

prepare generalist or specialised nurses for CNS or NP

roles. Transition curricula have the potential for lling in

educational gaps as nursing education in the country

evolves toward the master’s degree requirement.

In addition, it is recognised that there are countries that

have clear career tracks or career ladders and grading

(e.g. banding) systems in place for nursing role titles,

descriptions, credentials, hiring practices and policies.

These grading systems or level of roles will impact on

implementation of the APN (CNS or NP) as the grading

system stipulates a certain level of education and years

of experience at each level, including roles at advanced

levels. Such a grading system is likely to ensure that

nurses working in a specic grade perform at a more

consistent level since they would be viewed to have

similar education and experience. Protected role titles

with clear credentialing requirements help ensure con-

sistent role implementation at the desired level.

Most importantly, these guidelines emphasise that the

APN is fundamentally a nursing role, built on nursing

principles aiming to provide the optimal capacity to

enhance and maximise comprehensive healthcare

services. The APN is not seen as in competition with

other healthcare professionals, nor is the adoption of

the domains of other healthcare providers viewed as

the core of APN practice.

Chioma

GUIDELINES ON ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING 2020

12

CHAPTER TWO

THE CLINICAL NURSE SPECIALIST (CNS)

3

The Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) is one commonly identied category of Advanced Practice Nursing (APRN &

NCSBN 2008; Barton & Allan 2015; CNA 2019; Maier et al. 2017; Tracy & O’Grady 2019). This section describes

the historical background of the CNS, denes the role and explains how a scope of practice and education pro-

vide the foundation for the CNS. In addition, credentialing and regulatory mechanisms are dened as well as their

importance in establishing the identity and professional standard for CNSs.

2.1 ICN Position on the Clinical Nurse Specialist

3 It is acknowledged there are countries with Clinical Nurse Consultants (CNC) whose practice is viewed to be consistent with CNS practice

(Bryant-Lukosius & Wong, 2019; Carryer et al. 2018; Gardner et al. 2013; Gardner et al. 2016). The use of CNC is country specic and at times

used interchangeably with CNS, however, this guidance paper focuses on identifying the CNS.

The CNS is a nurse who has completed a master’s

degree programme specic to CNS practice. The CNS

provides healthcare services based on advanced spe-

cialised expertise when caring for complex and vulner-

able patients or populations. In addition, nurses in this

capacity provide education and support for interdiscip-

linary staff and facilitate change and innovation in

healthcare systems. The emphasis of practice is on

advanced specialised nursing care and a systems

approach using a combination of the provision of direct

and indirect clinical services (see Section 2.3 for den-

itions of direct and indirect care). This prole of the CNS

is based on current evidence of the successful pres-

ence of the role in some countries; however, often the

CNS role is present but invisible in settings where these

nurses provide a valuable service. Further research is

needed to clearly identify the diversity of the settings

and countries where the CNS practices.

As healthcare reform worldwide continues to gain

momentum, there will be opportunities for nurses in

CNS practice to meet the unmet needs of varied popu-

lations and diverse healthcare settings. Crucial to taking

advantage of these possibilities is the need to improve

understanding of the CNS in the Advanced Practice

Nursing context. In order to grasp an increased appre-

ciation and comprehension of the CNS, the requirement

for title protection, graduate education (minimum mas-

ter’s degree), and an identiable scope of practice as

part of a credentialing process, is seen as optimal.

2.2 Background of the Clinical Nurse Specialist

The expanded role of nursing associated with a CNS

is not a recent phenomenon. The term ‘specialist’

emerged in the United States (USA) in the 19

th

and

early 20

th

Centuries as more postgraduate courses in

specic areas of nursing practice became avail able

(Barton & East 2015; Cockerham & Keeling 2014;

Keeling & Bigbee 2005). The origin of the CNS emerged

from an identied need for specialty practices (Chan &

Cartwright 2014). Psychiatric Clinical Nurse Specialists

along with nurse anesthetists and nurse midwives led

the way. The growth of hospitals in the 1940s as well

as the development of medical specialties and technol-

ogies further stimulated the evolution of the CNS.

These nurses were considered to practice at a higher

degree of specialisation than that already present in

nursing and are viewed as the originators of the current

CNS role. Even though there has been an evolution of

role development internationally over the years, CNS

origins were seen to lie comfortably within the tradition-

ally understood domain of nursing practice and thus the

CNS was able to progress unopposed (Barton & East

2015).

Similarly, in Canada, CNSs rst emerged in the 1970s

as provision of healthcare services grew more com-

plex. The concept of the role was to provide clinical

consult ation, guidance and leadership to nursing staff

managing complex and specialised healthcare in order

to improve the quality of care and to promote evidence-

informed practice. CNSs were focused on complex patient

care and healthcare systems issues which required

improvements. The result of the CNS presence was

measurable positive outcomes for the populations they

cared for (CNA 2019).

The following reasons for the conception of the CNS

role were proposed by Chan and Cartwright (2014: 359):

•

Provide direct care to patients with complex

diseases or conditions

•

Improve patient care by developing the clinical skills

and judgement of staff nurses

•

Retain nurses who are experts in clinical practice

The CNS role has developed over time, becoming

more exible and responsive to population healthcare

needs and healthcare environments. For example, in

Sub-Saharan Africa, the CNS is well developed, par-

ticularly in the progress made in HIV management and

prevention for these vulnerable populations (personal

communication, March 2019, B. Sibanda). The funda-

mental strength of the CNS role is in providing complex

specialty care while improving the quality of healthcare

delivery through a systems approach. The multifa ceted

CNS prole, in addition to direct patient care in a clin-

ical specialty, includes indirect care through educa-

tion, research and support of other nurses as well as

healthcare staff, provides leadership to specialty prac-

tice programme development and facilitates change

and innovation in healthcare systems (Lewandowski &

Adamle 2009).

12

CHAPTER TWO: THE CLINICAL NURSE SPECIALIST (CNS)

13

2.3 Description of the Clinical Nurse Specialist

The CNS is a nurse with advanced nursing knowledge

and skills, educated beyond the level of a generalist

or specialised nurse, in making complex decisions in

a clinical specialty and utilising a systems approach to

inuence optimal care in healthcare organisations.

While CNSs were originally introduced in hospitals

(Delamaire & LaFortune 2010), the role has evolved

to provide specialised care for patients with com-

plex and chronic conditions in outpatient, emergency

department, home, community and long-term care

settings (Bryant-Lukosius & Wong 2019; Kirkpatrick

et al. 2013). Commonly, the provision of healthcare

services by a CNS includes the combination of direct

and indirect healthcare services (refer to Section 2.3)

based on nursing principles and a systems perspective

(CNA 2014; NACNS 2004; NCNM 2007). It is acknow-

ledged that indirect services of the CNS are highly val-

ued along with direct clinical care and should be taken

into consideration when dening scope of practice.

Although nurses who practice in various specialties

(e.g. intensive care unit, theatre/surgery, palliative care,

wound care, neonatal, gerontology) may consider them-

selves at times to be specialised nurses, the designated

CNS has a broader and extended range of accountabil-

ity and responsibility for improvements in the healthcare

delivery system, including an advanced level clinical

specialty focus. Based on postgraduate education at

a minimum of a master’s or doctoral degree, the CNS

acquires additional in-depth knowledge, critical thinking

and decision-making skills that provide the foundation

for an advanced level of practice and decision making.

2.4 Clinical Nurse Specialist Scope of Practice

The scope of practice for the CNS extends beyond the

generalist and specialised nurse in terms of advanced

expertise, role functions, mastery of a specic specialty

with an increased and expanded level of practice that

includes broader and more in-depth accountability. The

scope of practice reects a sophisticated core body of

practical, theoretical and empiric nursing and health-

care knowledge. CNSs evaluate disease patterns,

technological advances, environmental conditions and

political inuences. In addition, they interpret nursing’s

professional responsibility to serve the public’s need for

nursing services. CNSs function as expert clinicians in

a specialty and are leaders in advancing nursing prac-

tice by teaching, mentoring, consulting and ensuring

nursing practice is evidence-based/evidence-informed.

Table 1: Characteristics delineating Clinical Nurse Specialist Practice

THE FOLLOWING CHARACTERISTICS, IN VARYING COMBINATIONS, DELINEATE CNS PRACTICE

• Clinical Nurse Specialists (CNSs) are professional nurses with a graduate level preparation

(master’s or doctoral degree).

• CNSs are expert clinicians who provide direct clinical care in a specialised area of nursing practice.

Specialty practice may be dened by population (e.g. pediatrics, geriatrics, women’s health); clinical

setting (e.g. critical care, emergency); a disease/medical subspecialty (e.g. oncology, diabetes);

type of care (psychiatric, rehabilitation); or type of problem (e.g. pain, wound, incontinence).

• Clinical practice for a specialty population includes health promotion, risk reduction, and management

of symptoms and functional problems related to disease and illness.

• CNSs provide direct care to patients and families, which may include diagnosis and treatment of disease.

• CNSs practice patient/family centred care that emphasises strengths and wellness over disease or decit.

• CNSs inuence nursing practice outcomes by leading and supporting nurses to provide scientically

grounded, evidence-based care.

• CNSs implement improvements in the healthcare delivery system (indirect care) and translate high-quality

research evidence into clinical practice to improve clinical and scal outcomes.

• CNSs participate in the conduct of research to generate knowledge for practice.

• CNSs design, implement and evaluate programmes of care and programmes of research that address

common problems for specialty populations. (Fulton & Holly April 2018)

GUIDELINES ON ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING 2020

14

In dening the scope of practice for the CNS, identi-

cation of core competencies includes levels of direct

and indirect nursing care. These levels of care include

assisting other nurses and health professionals in

establishing and meeting healthcare goals of individ-

uals and a diverse population of patients (CNA 2014;

NACNS 2004).

•

Direct Care involves direct interaction with patients,

families and groups of patients to promote health

or well-being and improve quality of life. Direct care:

•

integrates advanced knowledge of wellness,

illness, self-care, disease and medical

therapeutics in a holistic assessment of people

while focusing on the nursing diagnosis

of symptoms, functional problems and risk

behaviours that have etiologies requiring nursing

interventions to prevent, maintain or alleviate;

•

utilises assessment data, research and theoretical

knowledge to design, implement and evaluate

nursing interventions that integrate delegated

medical treatments as needed; and

•

prescribes or orders therapeutic interventions.

•

Indirect Care involves indirect provision

of care through activities that inuence the care

of patients, but do not involve direct engagement

with populations. Examples include developing

evidence-based/evidence-informed guidelines

or protocols for care and staff development

activities. A CNS providing indirect care:

•

serves as a consultant to other nurses

and healthcare professionals in managing

highly complex patient care problems

and in achieving quality, cost-effective outcomes

for populations across healthcare settings;

•

provides leadership in appropriate use

of research/evidence in practice innovations

to improve healthcare services;

•

develops, plans and directs programmes of care

for individuals and populations and provides

direction to nursing personnel and others

in these programmes of care;

•

evaluates patient outcomes and

cost-effectiveness of care to identify needs

for practice improvements within the clinical

specialty or programme; and

•

serves as a leader of multidisciplinary groups in

designing and implementing alternative solutions

to patient care issues across the continuum

of care. (CNA 2014; NACNS 2004)

2.5 Education for the Clinical Nurse Specialist

A graduate programme (master’s or doctoral degree)

specifically identified for CNS education from an

accredited school/university or department of nursing

is viewed as important for providing the necessary

preparation for the CNS. The goal of the educational

programme is to prepare the nurse to think critically

and abstractly at an advanced level in order to assess

and treat patients/families/populations as well as to

teach and support other nurses and healthcare profes-

sionals in complex clinical situations. The educational

programme prepares the CNS to use and integrate

research into clinical practice, regardless of setting or

patient population.

Educational preparation is built on the educational foun-

dation for the generalised or specialised nurse in the

country in which the CNS will practice. In support of a

minimum standard for master’s level education, three

Canadian studies have demonstrated that self- identied

CNSs who have completed a master’s degree are more

likely to implement all recognised domains of Advanced

Nursing Practice compared to those who are not pre-

pared at the master’s level (Bryant-Lukosius et al. 2018;

Kilpatrick et al. 2013; Schreiber et al. 2005). Not only

do these studies demonstrate that graduate-prepared

CNSs function differently than the BScN-prepared

nurse, but they also show that the CNSs improve health

outcomes at the population health level, and further

contribute to innovation and improvement of the unit,

organisation and systems levels to improve access to

and quality of nursing and healthcare services.

2.6 Establishing a Professional Standard for the Clinical Nurse Specialist

In addition to following the professional standard for the

generalist nurse, the CNS is responsible for meeting

the standard or dened competencies for advanced

practice such as:

•

Providing nursing services beyond the level

of a generalist or specialised nurse that are

within the scope of the designated specialty

eld of advanced practice for which

he or she is educationally prepared

•

Recognising limits of knowledge and competence

by consulting with or referral of patients/populations

to other healthcare professionals when appropriate

•

Adhering to the ethical standards articulated

by the profession for APNs

A professional standard denes the boundaries and

essential elements of practice and connects the CNS

to the expected quality and competence for the role

or level of practice through the description of required

components of care. The identied criteria for the pro-

fessional standard serve to establish rules, conditions

and performance requirements that focus on the pro-

cesses of care delivery.

14

CHAPTER TWO: THE CLINICAL NURSE SPECIALIST (CNS)

15

Credentialing and Regulation

for the Clinical Nurse Specialist

Recognition to practice as a CNS requires submis-

sion of evidence to an authoritative credentialing entity

(governmental or nongovernmental agency) of suc-

cessful completion of a master’s or doctoral degree

programme in a designated clinical specialty from an

accredited school or department of nursing. The focus

of the educational programme must be specically

identied as preparation of nurses to practice as CNSs.

Continuing recognition to practice is concurrent with

renewal of the generalist nursing licence and all appro-

priate professional regulation for CNS practice in the

state, province or country in which the CNS practices.

In some countries, prescriptive authority is integral to

the CNS role and is governed by country, state or prov-

ince regulations based on the clinical area in which he

or she practices. In addition to completion of a CNS

educational programme, there may be a stipulation that

the CNS must complete an additional certication or

4 In its Regulation Series, ICN provides a Nursing Care Continuum Framework & Competencies (ICN 2008b) and denes the specialised nurse as a nurse

prepared beyond the level of a generalist nurse, authorised to practice as a specialist in a branch of the nursing eld.

credentialing process in order to demonstrate excel-

lence in practice and competence in the designated

eld or specialty in which he or she will practice. This

requirement is sensitive to the environment in which the

CNS initiative emerges and is developed.

Policies that provide title protection and clear creden-

tialing are important for role recognition and clarity.

Regulated title protection for the CNS is considered opti-

mal (CNA 2019). Studies on Advanced Practice Nursing

have found that countries in which titles and scope of

practice are regulated generally achieve greater role

clarity, recognition and acceptance by the consumer

and other healthcare professionals (Maier et al. 2017;

Donald et al. 2010). It is acknowledged that this is

especially important for CNSs as these nurses seek to

achieve increased visibility in demonstrating the import-

ance of their roles in healthcare systems worldwide.

Refer to Appendix 1 for Credentialing Terminology.

2.7 Clinical Nurse Specialists’ Contributions to Healthcare Services

Evidence from systematic literature reviews giving

examples of benecial outcomes of care provided by

a CNS include:

•

Improved access to supportive care through

collaborative case management to assess and

manage risks and complications, plan and

coordinate care, and monitoring and evaluation

to advocate for health and social services

that best meet patient/client needs

•

Enhanced quality of life, increased survival

rates, lower complication rates and improved

physical, functional and psychological well-being

of populations with complex acute or chronic

conditions

•

Improved quality of care

•

Improvement in health promotion

•

Contribution to the recruitment and retention

of nurses in the healthcare workforce

•

Decreased lengths of stay in hospital and reduced

hospital re-admissions and emergency department

visits

•

Reduction in medication errors in hospital wards

and operating rooms

(Brown-Brumeld & DeLeon 2010; Bryant-Lukosius

et al. 2015a; Bryant-Lukosius et al. 2015b;

Bryant-Lukosius & Martin-Misener. 2016;

Cook et al. 2015; Flanders & Clark 2010;

Kilpatrick et al. 2014)

The multifaceted nature of CNS practice and the vari-

ability by which these nurses adapt to diverse requests

has created confusion about what CNSs do. As a

result, this confusion challenges understanding of the

impact of the CNS role on clinical outcomes (Chan &

Cartwright 2014). Further collaborative research is

needed to improve this gap in knowledge. In addition,

CNSs and nurse leaders need to be more proactive in

articulating to healthcare funders and decision-makers

the value-added contributions of CNSs; this includes

their alignment with policy priorities for health system

improvement and contribution to healthcare policy

and decision-makers in achieving positive outcomes

(Bryant-Lukosius & Martin-Misener 2016).

2.8 Differentiating a Specialised Nurse

4

and a Clinical Nurse Specialist

It is acknowledged that in some countries there are

nurses with extensive experience and expertise in a

specialty who are not educated through a university

or post-graduate degree. For example, in Chile, the

specialised nurse is a highly recognised and valued

professional of the healthcare team and the healthcare

organisation, identied as such based on completion

of short courses or incidental training in addition to

extensive experience. It is envisioned that in the future,

a specialised nurse in Chile could proceed to enter a

CNS master’s degree educational programme in order

to promote change, implement system improvements

and enhance quality of care in clinical settings (per-

sonal communication, Pilar Espinoza, March 2019).

In its regional guide for the development of special-

ised nursing practice, the World Health Organization

Eastern Mediterranean Regional Ofce (WHO-EMRO)

provides the following denition:

A specialist nurse holds a current license as a general-

ist nurse, and has successfully completed an education

programme that meets the prescribed standard for spe-

cialist nursing practice. The specialist nurse is author-

ised to function within a dened scope of practice in a

specied eld of nursing.

(WHO-EMRO 2018: 7)

GUIDELINES ON ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING 2020

16

One criterion for designating a specialty for nursing

practice stipulates that the specialty is ofcially rec-

ognised and supported by the health system in the

country. In addition, levels of specialist nursing practice

progress to an advanced level of specialisation such

as the CNS based on completion of a clinical master’s

degree in the area of specialisation, and using the title

Registered Advanced Practice Nurse with area of spe-

cialty indicated. For example, Registered Advanced

Practice Cardiac Nurse (WHO-EMRO 2018).

Similarly, the European Specialist Nurses Organization

(ESNO 2015) recommends development of compe-

tencies for the CNS to clarify the position and prac-

tice of this nurse in Europe. This recommendation

includes building a framework corresponding to the

features of the specialty in which the CNS will practice.

Identication of consistent qualications would enable

the CNS the possibility to move more easily within the

member states of Europe. Consistent with the guide-

lines in this paper, ESNO identies the CNS as an

APN, educated within a clinical specialty at a master’s,

post-master’s or doctoral level.

From the perspective of workforce development and

healthcare reform, it is understood that delivery of

healthcare services requires a range of personnel

and that there would be larger numbers of special-

ised nurses in staff positions versus CNSs. CNSs with

advanced clinical expertise and a graduate degree

(minimum of master’s degree) in a clinical specialty

function collaboratively within healthcare teams. They

use a systems approach to coordinate directives of

specialty care in addition to providing direct healthcare

services. Table 2 below is a useful tool to distinguish the

characteristics of the specialised nurse and the CNS.

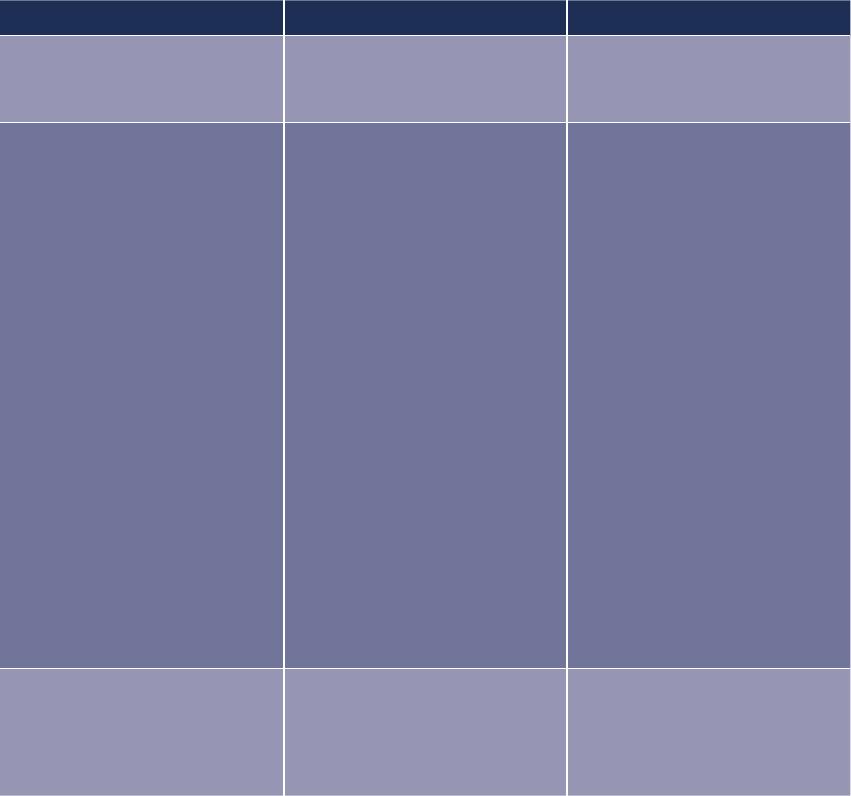

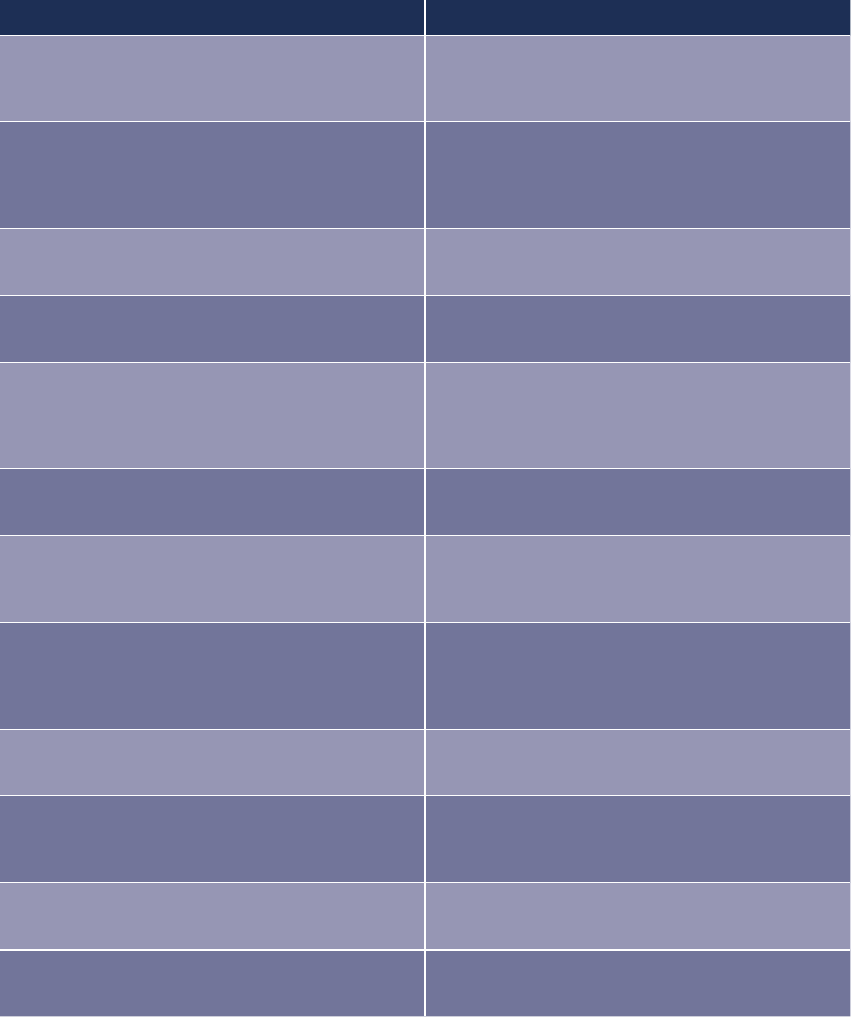

Table 2: Differentiating a Specialised Nurse and a Clinical Nurse Specialist

AREA SPECIALISED NURSE CNS

Education Preparation beyond the level

of a generalist nurse

in a specialty.

Master’s degree or beyond

with a specialty focus.

Scope of Practice

Job Description

Performs identied activities

in a specialty in line with

personal level of prociency

and scope of practice.

Formulates a care plan

in a specialty with identied care

outcomes based on nursing

diagnoses, and ndings

from a nursing and health

assessment, inputs from other

health team members

and nursing practice standards.

In addition to advanced

specialised direct clinical care,

formulates and mobilises

resources for coordinated

comprehensive care with

identied care outcomes.

This is based on CNS practice

standards, and informed

decisions about preventive,

diagnostic and therapeutic

interventions.

Delegates activities to other

healthcare personnel, according

to ability, level of preparation,

prociency and scope

of practice.

Advocates for and implements

policies and strategies from

a systems perspective to

establish positive practice

environments, including the use

of best practices in recruiting,

retaining and developing human

resources.

Professional Standard

& Regulation

Country standard for a licensed

generalist nurse in addition

to identied preparation

(experience and education)

as a specialised nurse.

Designated/protected CNS title

from a legislative or regulatory

agency. Preferred model is

transitioning to title protection if it

does not currently exist.

16

CHAPTER TWO: THE CLINICAL NURSE SPECIALIST (CNS)

17

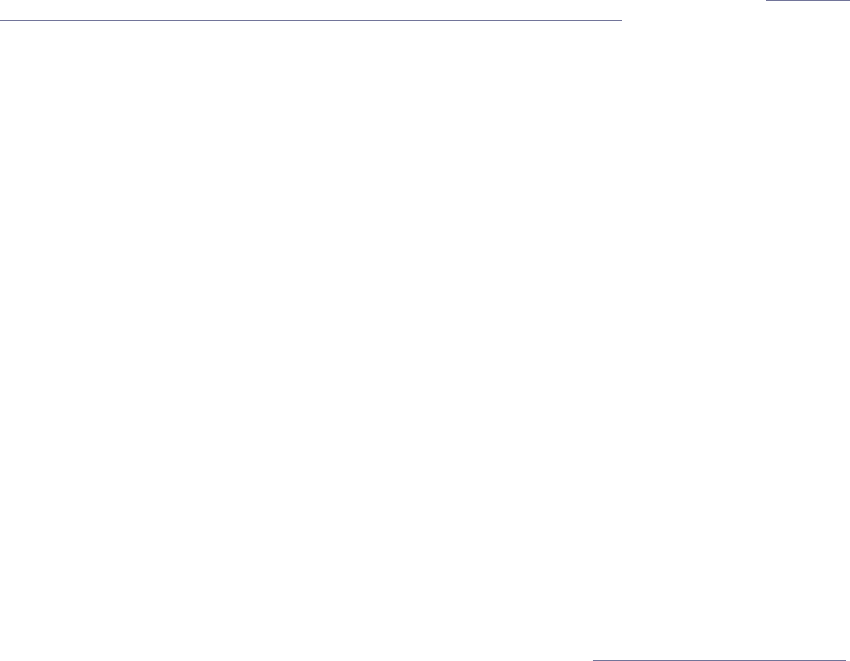

Figure 1: Progression from Generalist Nurse to Clinical Nurse Specialist

Generalist nurse

9 Diploma/Bachelors

Degree

Specialized nurse

9 Extensive experience

9 Specialized clinical courses

or modules and/or

on the job training

Clinical Nurse Specialist

9 Master’s Degree

or higher with a specialty

focus

Figure 1 depicts the progression from that of a gen-

eralist nurse to a CNS and then educated in a CNS

specic master’s degree programme. This progression

provides recognition of the foundation of specialised

clinical expertise based on the foundation of a general-

ist nursing education. A generalist nurse may proceed

to enter a CNS programme directly if the candidate

meets national and academic criteria for CNS prep-

aration. Completion of a minimum of a master’s degree

provides enhanced professional as well as clinical cred-

ibility for the nurse, who progresses and distinguishes

themselves as a CNS. The additional education and

clinical expertise gained with an academic degree has

the potential to further assure quality of care for diverse

populations. Based on standardised and accredited

academic programmes, this level of professional devel-

opment is viewed as essential when seeking to deliver

optimal safe and high-quality healthcare by enhancing

academic rigor, scientic reasoning and critical thinking.

Refer to Appendix 2, p. 33 for country exemplars of the

Clinical Nurse Specialist.

Carolyn Jones

GUIDELINES ON ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING 2020

18

CHAPTER THREE

THE NURSE PRACTITIONER

The Nurse Practitioner (NP) is one commonly identied category of APN (APRN 2008; Barton & Allan 2015;

Maier et al. 2017; Tracy & O’Grady 2019). This chapter presents the ICN position on NP, portrays the historical

background, describes the NP concept and explains how a scope of practice and appropriate education provide

the foundation for clinical practice. In addition, this chapter denes credentialing and regulatory mechanisms and

discusses their importance in establishing NPs in a variety of settings.

3.1 ICN Position on the Nurse Practitioner

Narrative descriptions and research demonstrate the

effectiveness of NPs within a variety of healthcare

settings. The international momentum for NP ser-

vices is increasing, however several themes need to

be confronted and managed to successfully launch

and sustain an effective NP initiative. Title protection

and a well-developed scope of practice sensitive to a

country’s healthcare system(s) and culture are critical.

The scope of practice and identied competencies for

the NP require a sound educational foundation along

with supportive credentialing and regulatory processes.

Continued research to provide evidence of the value

of NPs in provision of healthcare services will continue

to be needed to support the legitimacy of NP practice.

3.2 Background of the Nurse Practitioner

The concept of the NP was initiated in 1965 in the USA

based on a public health model to provide primary health-

care (PHC) to children lacking access to healthcare ser-

vices. The role was based on a person-centred, holistic

approach to care with the addition of diagnostic, treat-

ment and management responsibilities previously limited

to physicians. However, it was distinct from the medical

model in that it focused also on prevention, health and

wellness, and patient education (Dunphy et al. 2019). In

the mid-1970s, Canada and Jamaica followed the USA’s

development, aiming to improve access to PHC for vul-

nerable populations in rural, remote and underserved

communities. In the 1980s in Botswana, as the country

responded to healthcare reform and population needs

of the country spiraled, a Family Nurse Practitioner role

was launched. This was followed by introduction of the

NP in the four countries of the UK in the late 1980s. In the

1990s and early 2000s, additional countries introduced

NPs with ICN and the international healthcare commu-

nity noting signicant increased interest and development

worldwide (Maier et al. 2017; Schober 2016).

Since its beginnings, the focus of the NP has evolved to

include general patient populations across the lifespan

in PHC as well as to meet the complex needs of acute

and critically ill patients. Enthusiasm for the NP concept

and trends toward increasing access to PHC services

indicate that growing numbers of NPs are working to

expand care in diverse settings; this includes ageing

populations and those with chronic conditions in ambu-

latory settings and home care (Bryant-Lukosius &

Wong, 2019; Kaasalainen et al. 2010; Maier et al. 2017;

Schober 2016).

The NP concept often develops out of healthcare needs

as well as perceived criteria by individual, practicing

nurses who envision the enhancement of healthcare

services that can be provided to diverse populations

by NPs (Steinke et al. 2017). As the NP concept has

evolved, comprehensive PHC remains a common

focus with a foundation for practice that continues to be

based on nursing principles.

3.3 Description of the Nurse Practitioner

NPs are generalist nurses who, after additional edu-

cation (minimum master’s degree for entry level), are

autonomous clinicians. They are educated to diag-

nose and treat conditions based on evidence-informed

guidelines that include nursing principles that focus on

treating the whole person rather than only the condi-

tion or disease. The level of practice autonomy and

accountability is determined by, and sensitive to, the

context of the country or setting and the regulatory

policies in which the NP practices. The NP brings a

comprehensive perspective to healthcare services by

blending clinical expertise in diagnosing and treating

health conditions, including prescribing medications,

and with an added emphasis on disease prevention

and health management. NP practice is commonly

identied by the patient population, such as family,

paediatric, adult- gerontological or women’s health,

and may be practiced in PHC or acute care settings

(AANP 2018; CNA 2018; NMBI 2017; RCN 2018;

Scottish Government 2008).

3.4 Nurse Practitioner Scope of Practice

A scope of practice for the NP refers to the range of

activities (procedures, actions, processes) that a NP is

legally permitted to perform. This scope of practice sets

parameters within which the NP may practice by den-

ing what the NP can do, which population can be seen

or treated, and under what circumstances the NP can

provide care. Furthermore, once dened, the scope of

practice and associated competencies are linked to the

designated title and form the foundation for develop-

ing appropriate education and a professional standard

(ANA 2015; AANP 2015; Schober 2016).

The scope of practice for the NP differs from that of

the generalist nurse in the level of accountability and

responsibility required to practice. Where the NP con-

cept is recognised, establishment of a scope of practice

18

CHAPTER THREE: THE NURSE PRACTITIONER

19

is one way of informing the public, administrators and

other healthcare professionals about the role in order to

differentiate the qualied NP from other clinicians who

are not adequately prepared for NP practice or have not

been authorised to practice in this capacity.

ICN position on the Nurse Practitioner scope

of practice

A scope of practice for the NP describes the range

of activities associated with recognised professional

responsibilities consistent with regulation and policy in

the setting(s) in which the NP practices. Understanding

the country/state/provincial context in which the NP will

practice is fundamental when dening a scope of practice

for NP provision of healthcare services. In addition, it is

essential that development of a scope of practice focuses

on the activities of an NP that underpins the more complex

knowledge and skill sets of NP practice. ICN takes the fol-

lowing position for a Nurse Practitioner Scope of Practice:

The Nurse Practitioner possesses advanced health

assessment, diagnostic and clinical management

skills that include pharmacology management

based on additional graduate education (minimum

standard master’s degree) and clinical education

that includes specied clinical practicum in order to

provide a range of healthcare services. The focus of

NP practice is expert direct clinical care, managing

healthcare needs of populations, individuals

and families, in PHC or acute care settings with

additional expertise in health promotion and disease

prevention. As a licensed and credentialed clinician,

the NP practices with a broader level of autonomy

beyond that of a generalist nurse, advanced in-depth

critical decision-making and works in collaboration

with other healthcare professionals. NP practice

may include but is not limited to the direct referral

of patients to other services and professionals. NP

practice includes integration of education, research

and leadership in conjunction with the emphasis on

direct advanced clinical care.

Examples of Nurse Practitioner scope of practice

from three countries

Each country where the NP is well developed needs a

robust scope of practice. Three examples of NP scopes

of practice are presented here to provide guidance and

dialogue on this topic. Firstly, the American Association

of Nurse Practitioners’ (AANP) Scope of Practice for

Nurse Practitioners states that:

Nurse Practitioners assess, diagnose, treat and manage

acute episodic and chronic illnesses. They order, con-

duct, supervise and interpret diagnostic and laboratory

tests, prescribe pharmacological agents and non-

pharmacologic therapies as well as teach and counsel

patients. NPs are experts in health promotion and dis-

ease prevention. As licensed clinicians, NPs practice

autonomously and in coordination with other health care

professionals. They may serve as healthcare research-

ers, interdisciplinary consultants and patient advocates,

in addition to providing a wide range of health care ser-

vices to individuals, families, groups and communities.

(AANP, 2015)

The AANP scope of practice position paper also stipu-

lates the educational level for the NP and notes a level

of accountability and responsibility associated with pro-

viding advanced high-quality, ethical care to the public.

The Nursing Council of New Zealand (NCNZ 2017a:1)

describes the following NP scope of practice and links

the scope to six competencies that dene the know-

ledge, skills and attitudes required of them:

Nurse practitioners have advanced education, clinical

training and the demonstrated competence and legal

authority to practice beyond the level of a registered

nurse. Nurse practitioners work autonomously and in

collaborative teams with other health professionals to

promote health, prevent disease, and improve access

and population health outcomes for a specic patient

group or community. Nurse practitioners manage epi-

sodes of care as the lead healthcare provider in part-

nership with health consumers and their families/

whanau. Nurse practitioners combine advanced nurs-

ing knowledge and skills with diagnostic reasoning and

therapeutic knowledge to provide patient-centred

healthcare services including the diagnosis and man-

agement of health consumers with common and com-

plex health conditions. They provide a wide range of

assessment and treatment interventions, ordering and

interpreting diagnostic and laboratory tests, prescribing

medicines within their area of competence, and

admitting and discharging from hospital and other

healthcare service/settings. As clinical leaders, they

work across healthcare settings and inuence health

service delivery and the wider profession. Nurse

Practitioner Competencies are presented next:

1. Demonstrates safe and accountable Nurse

Practitioner practice incorporating strategies

to maintain currency and competence.

2. Conducts comprehensive assessments

and applies diagnostics reasoning to identify

health needs/problems and diagnoses.

3. Develops, plans, implements and evaluates

therapeutic interventions when managing

episodes of care.

4. Consistently involves the health consumer

to enable their full partnership in decision making

and active participation in care.

5. Works collaboratively to optimise health outcomes

for health consumers/population groups.

6. Initiates and participates in activities that support

safe care, community partnership and population

improvements.

GUIDELINES ON ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING 2020

20

In the Republic of Ireland, Registered Advanced Nurse

Practitioners (RANP) also work within an agreed scope

of practice and meet established criteria set by the

Nursing and Midwifery Board of Ireland (NMBI 2017).

Autonomy for the NP has been highlighted within the

scope of practice by designating that the Advanced

Nurse Practitioner (ANP):

…is accountable and responsible for advanced levels of

decision-making which occur through management of

specic patient/client caseload. ANPs may conduct com-

prehensive health assessment and demonstrate expert

skill in the clinical diagnosis and treatment of acute and/

or chronic illness from within a collaboratively agreed

scope of practice framework alongside other healthcare

professionals. The crucial factor in determining Advanced

Nursing Practice, however, is the level of decision-

making and responsibility rather than the nature or dif-

culty of the task undertaken by the practitioner. Nursing

or midwifery knowledge and experience should continu-

ously inform the ANPs/AMPs decision-making, even

though some parts of the role may overlap the medical or

other healthcare professional role.

(NCMN, 2008b, p.7)

In the Republic of Ireland, this description of autonomy

is designated for both the ANP and Advanced Midwife

Practitioner (AMP).

This section emphasises the signicance of establish-

ing a scope of practice for NPs and provides examples

to consider when developing an NP scope of practice.

Identifying a scope of practice is sensitive to country

context and the healthcare settings in which the NPs

will practice. In addition, the educational programme

and curriculum design should be in alignment with the

scope of practice and competencies expected of the

NP. This is discussed next in Section 3.5.

3.5 Nurse Practitioner Education

Nurse Practitioner education varies internationally and

is inconsistent; however, a master’s degree at a post-

graduate level is considered the minimum standard for

entry level NP practice with a designation that the pro-

gramme is specically identied for the preparation of

NPs (CNA 2008; CNA 2019; Fagerstrӧm 2009; Finnish

Nurses Association 2014; NCNZ 2017b; NMBI 2017).

In the USA, there is a trend for a doctor of nursing prac-

tice (DNP) degree as entry level for NP preparation.

The credibility and sustainability of the NP concept is