NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES

CROSS-SUBSIDIZATION OF BAD CREDIT IN A LENDING CRISIS

Nikolaos Artavanis

Brian Jonghwan Lee

Stavros Panageas

Margarita Tsoutsoura

Working Paper 29850

http://www.nber.org/papers/w29850

NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH

1050 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

March 2022

We have benefited from comments by Claudia Robles-Garcia, Sascha Steffen (discussant), and

participants at AFA, AEA, Frankfurt School, Columbia Business School, RCEA, and ECB.

Tsoutsoura gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Fama-Miller Center for Research

in Finance at Chicago Booth. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been

peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies

official NBER publications.

© 2022 by Nikolaos Artavanis, Brian Jonghwan Lee, Stavros Panageas, and Margarita

Tsoutsoura. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be

quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the

source.

Cross-subsidization of Bad Credit in a Lending Crisis

Nikolaos Artavanis, Brian Jonghwan Lee, Stavros Panageas, and Margarita Tsoutsoura

NBER Working Paper No. 29850

March 2022

JEL No. E43,E44,G01,G21,G3

ABSTRACT

We study the corporate-loan pricing decisions of a major Greek bank during the Greek financial

crisis. A unique aspect of our dataset is that we observe both the interest rate and the “breakeven

rate” of each loan, as computed by the bank’s own loan-pricing department (in effect, the loan’s

marginal cost). We document that low-breakeven-rate (safer) borrowers are charged significant

markups, whereas high-breakeven-rate (riskier) borrowers are charged small and sometimes even

negative markups. We rationalize this de-facto cross-subsidization of riskier borrowers by safer

borrowers through the lens of a dynamic model featuring depressed collateral values, impaired

capital-market access, and limit pricing.

Nikolaos Artavanis

Virginia Tech

1016 Pamplin Hall

Blacksburg, VA 24061

Brian Jonghwan Lee

Columbia Business School

665 West 130th Street

New York, NY 10027

Stavros Panageas

Anderson School of Management

University of California, Los Angeles

110 Westwood Plaza

Los Angeles, CA 90095-1481

and NBER

Margarita Tsoutsoura

SC Johnson College of Business

Cornell University

Ithaca, NY 14853

and NBER

1 Introduction

A common concern among macroeconomi sts and financial economists is that the cr ed i t

market is distorted duri n g a financial crisis. The concern can be summarized as follows:

banks may be reluctant to terminate loans, because of depressed collateral values. As a

result, worse-performing firms are charged interest rates below a “fair rate” in order to

keep these firms “afloat.” In an effort t o make up the losses, banks overcharge healthy and

growing firms that d on ’ t have many funding alternatives during a crisis. The result is a

de-facto cross-subsidization of weaker firms by stronger firms, wh i ch misallocates credit a n d

prolongs the fina nci a l crisis.

A common challenge in testing this cross-subsid i za ti o n hypothesis is determining whether

a given loa n i s upcharged or is extended at preferential terms. Such a determination requi r es

knowledg e of the “fair” or “breakeven” rate for that loan. By breakeven rate we mean the

interest rate that would make the lender break even, tak i n g into account the lender’s fun d i n g

rate and operating costs, as well as the borrower’s probability of default times the expected

loss upon defau l t (taking into account coll a t era l ) and any regulatory charges associated with

the loan. In effect, the breakeven rate is the marginal cost of the loan from the lender’s

perspective. To address this limitation, the l i ter a t ure typically imputes the breakeven rate

in some indirect manner.

1

As a resu l t , the theory ends up being test ed jointly with the

i

ndirect imputation method, resulting in a “joint hypot h esi s” problem.

In this paper, we provide direct evidence in support of th e cross-subsidizati on hypothesis,

by using a dataset that contains loan-level breakeven rat es. The dataset pertains to the large

corporate portfo l i o of a major Greek bank at the height of the recent Greek financial crisis.

The unique a spect of the dataset is th at besides loan-level info rm a t i on (actual interest rate,

maturity) and firm-level informatio n , we also observe the loan-level breakeven rate that

the bank’s own loan-pricing department supplies to the loan managers ahead of the loan

negotiations. This allows a direct observation of the difference between the actual and

breakeven rate, which we r efer to as the “markup” of each loan.

Our main finding is th a t the bank charges an interest rate well above the breakeven

1

We summari ze some indirect approaches in our discussion of the literature.

1

rate to comparatively safe borrowers (low-breakeven-ra te borrowers). By contrast, the bank

charges a zero, and sometimes even negat i ve, marku p to its riskier loans (high-breakeven-

rate borrowers). Importa ntly, because the loans in our sample are performin g loans, we are

able to show that thepatt er n of cross-sub si d i za ti o n app l i es even within the set of performing

loans, and our conclusions are not confined to a narrow comp ar i so n between performing and

non-performing loan s.

We nex t describe in greater detail the theoretical motivation behind our tests, the context

of our empirical analysis, and our key findings.

To provide a framework for our empirical results, we start by building a dynamic corpo-

rate fi n an ce model. The model is tailored to capture the specific institution al and historical

context o f o u r empirical analysis, but its key features are fairly standard and broadly used in

the literature. In the m odel, a borrower needs funds and a competitive b a n k provides them.

We study this model during a “crisis” and a “post-crisis” regime. In the p ost -cr i si s regime,

the bank has friction-less access to capital markets and the collateral values of capital are

high eno u gh that terminat i n g low profitability borrowers is p r o fi t ab l e. By contrast, when

the economy is in a crisis, we assume (a) the bank loses its frictionless access to capital

markets and has limited or no access to new capital and (b) the collateral values of capital

are temporarily depressed.

We sh ow loan pricing differs for low-profitability and high-profitab i l i ty borrowers. The

interest rate for low-profitability borrowers is disconnected — and may even be lower than

— the loan’s marginal cost, because of the real option to wait unti l either collateral values

rebound or the firm productivity rebounds. For such borrowers, the bank simply extracts

what each low-profitability borrower can afford to pay. At the same time, the reluctance

of competitor banks to terminate their own low-productivity projects and their ina b i l i ty to

raise new capital in i nternational financial markets implies that high-pro fi ta b i l i ty borrowers

cannot be poached easily by competitors. Thus, they can be charged a markup, up to

the point where competitor banks are ind i ffer ent between poach i n g the loan or not (“limit

pricing”).

The theoretical model makes two basic predictions: First, a cross-sectional regression of

actual loan rates on their breakeven rates should have a coefficient less than one, reflecting

2

that financial l y healthier borrowers are upcharged, relative to weaker ones. (We label this

prediction an imperfect “pass through” of the br eakeven rate to the actual rate.

2

) Second,

pass through should be asymmetric: The pass-throu g h coefficient should be higher for high-

profitability firms, whose loans are priced according t o a limit prici n g rule, and weaker for

firms whose loans are priced according to what th e borr ower can afford to pay.

We test these predictions using a dataset that includes the universe of l a rg e-fi r m loans

of a major, systemic bank in Greece. We expl o i t a regulatory reform in the Greek b an k i n g

system that required financial instituti on s to develop new, transparent loan -l evel pricing

guidelines. The requirement was imposed by the the monitoring instituti o n s of the Greek

MoU (Memorandum of Under st a n d i n g) following the recapitalization of Greek banks in 2012.

In response to these mandates, each systemic bank had to develop its own pri ci n g model

independently, adhering to two requirements. Fi r st , the pricing model had to be formulaic

and data d r i ven (i.e., reflect balance-sheet information rat h er than subjective assessments),

follow the Basel gu i d el i n es and be used to com p u t e capital charges at the loan level. Second,

it had to be applied uniformly to all loans of th e same class with common parameters for no n -

firm-specific variables. The ultimate output should be a loan-level breakeven rate, defined

as the interest rate that makes the bank break even on the loan. The new pricing model

went into effect in 2015, approximatel y two quarters before the peak of the Greek financial

crisis. Importantly, after the introduction of the new pricin g guidelines, loans extended with

interest rates below the breakeven rate required internal approval that stated the justification

for the discount.

The introduction of the new pricing guidelines has a profound impact on loan pricing.

Loan managers heed the new guidelines a n d start “p assi n g through” the breakeven ra tes

to the loans that are initia ted or renewed. Indeed , the breakeven rate appears to be the

only variable that matters for loan pricing after the introduction of the new prici n g guide-

lines. This finding is in contrast to the pre-guidel i n e period, where the (ex-post calculated)

breakeven rate plays n o role for loan pricing. At the same t i m e, variables capturing non-

economic factors (polit i ca l connections of board members, du m my variables that in d i cat e a

2

A mathematically equivalent formulation of the imperfect pass-through hypothesis is that the difference

between the actual and breakeven rate (the markup) is decreasing in the breakeven rat e.

3

tightl y held firm, etc.) seem to matter for loan pricing during the pre-gui d el i n e period, but

are driven out post-guid el i n e.

Having established that the new pricing guidelines weren’t simply ignored, but instead

had a profound impact on loan pricing, we test for imperfect pa ss-t h ro u g h of th e brea keven

on the actual rate aft er the introduction of the new pricing guidelin es. Consistent wit h our

model, the coefficient o f a regr essi o n of th e actual rate on the breakeven rate is al ways below

one, implying markups are decreasing in the breakeven rate. This fi n d i n g is pervasive. We

even obser ve several instances in which loans are extended at below-breakeven rates, with

loan managers choosi n g to go through the arduous internal-app r oval process.

We also document a pricing asymmetry. The pass-through coefficient (controlling for

time an d firm fixed effects) is about 0.4 for rel a ti vely safe borrowers (borrowers with below-

median break-even rates on the da t e of the introduction of the new pricing guidelines). The

same coefficient i s essentially 0 for rel at i vely risky borrowers (borrowers with above-median

break-even rates on the date of the introducti o n of the new pricing scheme). This finding

is consistent with the view that the pricing decisions for the riskier borrowers are decoup l ed

from th e riskiness of their loan. Instea d , they are mostly dictated by the borrower’s ability

to pay, consistent with our theoretical mod el .

Next, we examine possible alternative interpretations of our results. We investigate

whether the source of the imperfect pass-through is due to managers’ possessing some su-

perior informat i on on the long-term prospects of the firm, which induces them to moderat e

the impact of th e breakeven rate on their loan-p r i ci n g decisions. Utilizing a test analogous

to Chiappor i & Salanie (2000), we test whether a low (h i g h ) markup correlates with subse-

q

uent improvement (deterioration) in the borrower’s credit rating. We find that the markup

has no abi l i ty to predict future changes in the borrower’s credit rating — after controlling

for the cur r ent credit rating. Therefore, the source of the imperfect pass-through is not

due to managers’ possessing some superior inform a t i on on the lon g -t erm prospects of the

firm, which induces them to moderate the impact of the breakeven rate on th ei r loan-pricing

decisions. Our results are also not driven by lo a n managers choosing to pass through only

the component of the breakeven rate that is narr owly linked with the regulatory charge of

the loan. Isolating the component of the breakeven rate that corresponds to the regulatory

4

charge of each loan, and including it as a separate regressor (alongside the breakeven rate)

does not change our results.

Our results relate to several strands of the l i t era t u r e. The literature on zombie lend-

ing (Peek & Rosengren (2005); Caballero, Hoshi & Kashyap (2008); Giannetti & S i m o n ov

(2013)) has exami n ed the widespread practice by Japanese banks in th e 9

0s to provide credit

to insolvent firm s. Much of the liter at u r e sh i ft ed its focus to Europe dur i n g t h e sovereign

debt crisis (Ach ar ya, Imbierowicz, Steffen & Teichma n n (2020); Acharya, Eisert, Eufinger &

Hi

rsch (2019); Acha r ya, Crosignani, Eisert & Eufinger (2020); Schivardi, Sette & Tabellini

(2021); Blatt n er , Farinha & Rebel o (2019); Banerjee & Hofmann (2018); McGowan, Andrews

&

Millot (2018); Albertazzi & Marchetti (2010)). In a contempora n eou s paper, Faria-e Cas-

t

ro, Paul & Sanch´ez (2021) provide evidence of “evergreening” in the US using supervisor y

data from the Federal Reserve. As mentioned earlier, our dataset allows for a direct test of

the cross-subsidi zat i o n hypothesis, without having to rel y on some indirect inference for the

“fair” (or “breakeven”) rate of each lo a n .

3

In addition, although related to the liter a tur e

o

n zombie lending, our paper is not just about zombie loans. Because we can observe the

markup of each loan, we are able to document a broader pattern of cross-subsidization of

riskier borrowers by safer borrowers across performing loans.

A large literature investigates “cross-subsidization”, especially in asymmetric-information

settings. Puelz & Snow (1994) and Chiappori & Salanie (2000) prov i d e early examples o f

t

esting for cross-subsidization from safe consumers to risky consumers in the auto insuran ce

market. Similar notions of cross-subsidizati o n have been examined in other areas including

the mortgage ma r ket (Hurst, Keys, Seru & Vavra (2016); Gambacorta, Guiso, Mistrulli,

P

ozzi & Tsoy (2019)); student loans ( Ba chas (2019)), and health insurance (Finkelstein

(2004), Finkelstein & McGarry (2006), Aizawa & Kim (2018)). In a recent paper, Nelson

(2020) shows a regulatory ch an g e in the US credit card ma rket restric

ted cross-sectional

passthrough across credit card consumers, thu s providing cheap er credit to risky consumers

while safe consumers received overpr i ced credit. Our notion of “cross-subsidization” differs

from the above literature in that it pertains to knowingly charging different markups to clients

3

Prior research on zombie firms examined interest cover age ratio, credit rating, delinquency, unreported

loss, and accounting variables to ascertain whether a bank subsidized a given firm.

5

who are observably di ssi m i l ar (as reflected in their different breakeven rates), as opposed to

the cro ss-su b si d i zat i on that arises when borrowers who a re observably similar (but dissimilar

on unobservables) are pooled together and charged the same pri ce.

Screening models of cross-subsidization provide an alternative framework to ours to cap-

ture cross-sub si d i zat i o n of observably dissimilar clients, as reveal ed by the client’s choices.

Several reasons seem to suggest su ch a framework may not be well suited for the specific

context we study in this paper. First, such model s do not contain clear implications about

the pattern of cross-subsidizati o n . Oligopolistic screening introdu ces a ma r ku p , but leads to

ambigu o u s prediction s as to whether the markup per dollar loaned should be increasing or

decreasing with borrower riskiness.

4

Second, i n such models, the markup is typically posi-

t

ive across a l l credit qualities,

5

whereas in our data , we observe several instances in which

loan managers extend loans at below-breakeven rates, hinting at the presen ce of a “real op-

tion.” Third, as mentioned earlier, in section 7.1, we perform a test similar in spirit to the

a

symmetric-information test of Chiap pori & Salanie (2000)

6

and find that the actual interest

rate on a loan does not appear to have superior ex -post predictive abi l i ty about a bo rr ower’s

future prospects.

Due to its dy n a m i c nature, our model resembles the large banking literature on relation-

ship lending.

7

Given the focus on the Greek financial crisis, t h e p a per also co

ntribu t es t o the

literature on i m p ai r ed financial intermediation in the context of the European Sovereign Debt

Crisis (Acharya, Drech sl er & Sch n ab l (2014); Ach a r ya, Eisert, Eufinger & Hirsch (2018);

Acharya, Imbierowicz, Steffen & Teichmann (2020)). Several articles examine the relation-

s

hip between bank market power and interest rate pass through (Hannan & Berger (1991);

Berger & Udell (1992); Neumark & Sharpe (1992); Zentefis (2019)). For instance, Sch ar fst ei n

4

For instance, the oligopolistic screening model of the lending market by Villas-Boas & Sch mi dt -M oh r

(1999) has parameter-dependent implications about whether the markup should be higher or lower for riskier

loans. In an industrial organization framework similar to the seminal Mussa & Rosen (1978) non-linear

pricing framework, Rochet & Stole (2002) show that as competition intensifies, their oli gopolistic model

converges to a fixed fee model, independent of revealed borrower characteristics.

5

See, for example,Villas-Boas & Schmidt-Mohr (1999).

6

Chiappori & Salanie (2000) test for a correlation between ex-ante choices of auto-insurance cover

age and

ex-post accidents. In our context, we test whether a seemingly low interest rate tends to predict positive

revisions to a bor r ower’s future rating.

7

See, for example, Diamond (1991); Rajan (1992); Petersen & Rajan (1994); Boot & Thakor (2000);

Hachem (2011).

6

& Sunderam (2016) show how bank market power can limit mon et a ry -policy tr a n smission

to mor t g ag e rates. The noti o n of limited pass-through in th ese papers is different fro m that

in our paper. For us, limited pass-through is primaril y a cross-sectional no t i on : it refers to

a less than one-for-one relation between the actual and brea keven rate across different loans

at the same point in time.

2 Model

In this sect i on , we propose a stylized model to aid the interpr

etation of our empirical

results. The model contains several elements th at are meant to capture th e specific economic

context of Greek banks and borrowers during the time period of our study. Al th o u g h a few

of the modelli n g choices are m o t i vated by the specific historical experien ce of Greece, t h e

assumptions of the model are standard and would apply to any banking system in crisis.

In particular, we con si d er a basic dynamic corporate finance problem whereby a lender

and a borrower split the cash flows of a project during times of “cri si s” and “post crisis.”

Our focus is on the state of crisis. We make three assumptions about the crisis, motivated by

the ci rcu m st a n ces Greek firms and banks faced during ou r sample period: (a) Greek banks

had limited access to international capit al markets, (b) collateral values of all projects were

depressed during this time period, and ( c) shar eh ol d er s had essentially no abili ty to perfor m

equity injections.

To fix ideas, we star t by presenting first the post-crisis version of the model and then

work backwards to present the model solution during the time of the cri si s. Specifical l y, we

assume that the economy is in a state of crisis at time 0. At some random, exponentially

distributed time τ, the eco n omy transits to th e post-crisis state. The arrival of this event

occurs with a hazard rate ρ per unit of time dt. Throughou t , sup er scr i p t “c” denotes a

variable during the state of crisis.

2.1 Post crisis

Throughout, we assume that a ty p i ca l firm produces a stochastic cash-flow process π

t

per unit of capital and per unit of ti m e d

t. For simplicity, we assume (a) each firm only

7

uses one unit of capital, and (b) this cash-flow process takes two values according to an

(idiosyncratic and firm-specific) Markov regime-switching process.

8

The cash -fl ow process

of firm i takes th e value π

H

i

when the firm is in regime H a

nd the value π

L

i

when the firm

is in regime L. The hazard rate of l eaving regi m e H and transitioning to regime L is equal

to p

L

i

, and the hazard rate of the reverse transition is p

H

i

. The transitions between the two

regimes are independent across firms. Moreover, firms can differ in terms of the parameter s

p

H

i

, p

L

i

, π

H

i

,and π

L

i

.

Wh

ile keeping in mind that t h e parameters p

H

i

, p

L

i

, π

H

i

, and π

L

i

can differ across firms,

h

ereafter, we drop the subscript i and u se the simpler notation p

H

, p

L

, π

H

, and π

L

.

In the post-crisis economy, banks are perfectly competitive and can borrow and lend

freely at the rate r

∗

in international capital markets. The (representative) ban

k provides the

unit of the capital stock to the firm an d in exchange obtains a cash-flow stream R

j

i

, which

depends on firm i and the profitability regime j ∈ {H, L} of firm i. We normalize the price

of one unit of the capital st ock to 1. At any point in tim e, th e bank can liqu i d a t e the capital

stock and obtain a value C

∗

i

< 1. I

n oth er words, the difference between the price of capi t a l

and its liquidated value, 1 − C

∗

i

> 0, is the deadweight cost of bankruptcy. To economize

notation, we drop the subscript i and write R

j

and C i

nstead of R

j

i

and C

i

(respectively).

Throughout, we abstract from corporate cash accumulation by assuming shareholders

have a sufficiently high discount rate λ.

9

For simplicity, we also suppress equity issuance by

a

ssuming shar eh ol d er s cannot inject any additional equity to the firm, and hence, R

j

≤ π

j

,

for j ∈ {H, L}. Finall y, all debt is short term (i.e., needs to be constantly rol l ed over) and

the bank can withdraw th e un i t of capital at any time. Similarly, companies can refinance

their loans at no cost by repaying the current bank in the full amount and obtaining a new

loan from another competi t i ve bank.

The value of a deb t contract V

t

from the perspective of a bank obey s a standard asset-

p

ricing rel at i o n sh i p . When t h e profitability of the firm is in regime H, the value of the debt

8

Allowing mu l t i pl e p r ofit ab i li ty r egimes or allowing firms to choose th e scal e of t hei r capital is strai ght-

forward, but is immaterial for the purposes this paper. Abel & Panageas (2020a) present a version of this

model that allows the firm to vary its scale by adjusting the units of the capital stock.

9

Abel & Panageas (2020b) study a version of this model th at allows for cash accumulation and show a

h

igh-enough shareholder discount rate leads to no cash accumulation.

8

contract is

R

H

|{z}

Interest paid to the bank

+ p

L

!

max{V

L

, C

∗

} − V

H

|

{z }

expected capital loss upon regime change

= r

∗

V

H

|{z}

required rate of return

(1)

S

imilarly, the pricing equation when the firm i s in regime L is

R

L

|{z}

Interest paid to the bank

+ p

H

!

V

H

− V

L

|

{z }

expected capital gain upon regime change

= r

∗

V

L

|{z}

required rate of return

. (2)

Because banks are competitive, it must be the case that both V

H

≤ 1

and V

L

≤ 1.

Otherwise, a competi t or bank can offer to refin an ce the loan, whose face value is 1. At the

same t i m e, a bank will not initiate a loan unless it makes non-negative profits, which leads

to V

H

= 1, a

nd hence, by equation (1), we have

R

H

= r

∗

+ p

L

!

1 − max{V

L

, C

∗

}

. (3)

We assume

π

H

> r

∗

+ p

L

(1 − C

∗

) , (

4)

which implies R

H

< π

H

, an d hence, the bank can feasib l y charge t h e interest rate R

H

that

allows it to break even.

Using V

H

= 1 inside ( 2 ) gives

R

L

+ p

H

!

1 − V

L

= r

∗

V

L

(5)

T

he bank will fin d it optimal t o liquidate the firm whenever V

L

< C

∗

. T

he maximum

possible value of V

L

is obtained by setting R

L

= π

L

, in which case equation (5) becomes

V

L

=

π

L

+ p

H

r

∗

+ p

H

. (6)

Further, we assume

π

L

<

!

r

∗

+ p

H

C

∗

− p

H

, (

7)

9

and therefore, (6) implies V

L

< C

∗

, which in turn implies liquidating the firm in regime

L is optimal. We summarize the above discussion in the following proposition

Proposition 1. Assume conditions (4) and (7) hold. Then,

R

H

= r

∗

+ p

L

(1 − C

∗

) , (

8)

and the firm gets liquidated once it enters the low-profitability regime L.

The post-crisis interest rate (8) is intuitive and familiar. The bank charges its own

f

unding rate r

∗

along with an additional compon ent reflecting the probability of default p

L

times the loss upon default (1 − C

∗

). No

te that because we have allowed p

L

to differ across

firms, so will the interest rate R

H

that the bank charges t o different firms, dependin g on

each firm’s default risk.

2.2 Crisis

The focus of our analysi s is on the state of crisis. The crisis-version of the model is

identi cal to the post-crisis versio n , except that: (a) collateral values are lower during the

crisis period, so that liquid at i o n of a firm al l ows the bank to recover onl y C < C

∗

per unit of

c

apital, and (b ) banks have limited access to international capital markets; therefore, they

have to fin an ce new projects using their internal funds. This second assumption is mostly for

expositional ease and can be relaxed to al l ow banks to have costly access to capital markets,

as we discuss at the end of this section. Although not essential for our results, we also allow

the required rate of return of bank sh a reh o l d er s (r) to differ from its post-crisis level (r

∗

) .

L

etting V

H,c

(V

L,c

) denote th e value of debt when a gi ven firm i i

s in the H (resp. L)

regime and the economy is in the crisis state “c,” we obtain the pricing equation:

R

H,c

+ p

L

!

V

L,c

− V

H,c

+ ρ

!

1 − V

H,c

= r

V

H,c

. (9)

The first two terms on the l eft -h a n d side of (9) are the same as dur i n g the pre-crisis

p

eriod, namely, the sum of the interest charged by the ba n k, R

H,c

, p

lus the expected capital

loss upon transition to the low-profitability regime, p

L

!

V

L,c

− V

H,c

. The third term, reflects

10

the expected change in the value of the debt upon transition to the post-crisis state, which

is the prod u ct of the transition hazard ρ times the change i n the value of debt, 1 − V

H,c

.

Similarly, for a firm that finds itself in regime L, the debt-pricing equation is

R

L,c

+ p

H

!

V

H,c

− V

L,c

+ ρ

!

C

∗

− V

L,c

= r

V

L,c

. (10)

Clearly, a bank will not find it profitable to liquidate a loan as long as V

L,c

≥ C

.

The assumption that banks have to finance projects from i nternal funds limits compe-

tition between banks for fir m s in the H regime. To poach a borrower in the H r eg i m e, a

rival bank has t o liquid a t e

1

C

of its existing loans, so that it can raise the face value of the

l

oan it is poaching,

1

C

C = 1. Clearly, the rival bank finds it profitable to engage in such

poaching only if V

H,c

≥

D

C

, where D is the minimal value V

L,c

across all debt contracts that

the rival bank is financing. (The heterogeneity of the parameters p

H

, p

L

, π

H

, π

L

, e

tc. across

firms implies V

H,c

and V

L,c

differ a cr os s firms). Because V

L,c

≥ C for any debt contract of

any bank, it must be the case that

D

C

≥ 1.

In summary, unlike in the post-cri si s regime, where the no-poaching condition amou nts

to V

H

= 1, d

uring a crisis, the no -poaching condition leads to V

H,c

=

D

C

, where

D

C

≥ 1. We

obtain the following proposition.

Proposition 2. Assume conditions (4) and (7) hold, and in addition, assume

r

∗

− p

H

(1 − C

∗

) <

r

D

C

+ ρ

D

C

− C

∗

, (

11)

and

π

L

+ p

H

D

C

+ ρC

∗

r + ρ + p

H

> C. (12)

Then, R

L,c

= π

L

and

R

H,c

= r +

(r + ρ)

D

C

− 1

+ p

L

D

C

− V

L,c

, (13)

where

V

L,c

=

π

L

+ p

H

D

C

+ ρC

∗

r + ρ + p

H

<

D

C

. (14)

11

Remark 1. Note that (sufficiently small) values of C and (sufficiently large) values of C

∗

always exist, such that conditions (7) and (12) both hold.

Proposition 2 states th a t during a crisis, liquidating the firm in regime L i

s n ot optimal.

The intuition is that the low collateral values during the crisis act as a disincentive for

liquidations. Hen ce, firms that would get liquid at ed in the post-crisis state survive during a

crisis.

Another interesting implication of propositi o n 2 is that while the economy is in a crisis,

t

he bank makes economic “rents” from projects in regi me H. To see this in the simplest

possible way, assume r = r

∗

. T

hen, the fact that V

H

=

D

C

> 1 implies that th e expected

present value of the interest paid by fi r m s that find themselves in regime H during a crisis

exceeds the value of the capital provided by the bank (whose value we have normalized to

1). The reaso n is that the difficulty of rival banks to raise n ew capital becomes a de-facto

impediment to competiti on between banks.

The shareholder s of firms i n the L regime benefit during a crisi s. In post-crisis times, the

firm gets liquidated an d these shareholders receive nothing. By contrast, during the crisis,

the firm stays alive in the L regime. Although the bank appropriates all ca sh flows wh i l e

the firm is in the L regime

!

R

L,c

= π

L

,

the firm may still transi t back into the H regime

before the economy transitions to the post-crisis reg i m e. Given that R

H,c

< π

H

, and that

the probability of transi t i o n i n g to th e H regime is positive, the shareholders of the firm in

regime L own a claim with a positive expected present value.

This phenomenon whereby banks in a time of crisis essenti al l y subsidize their rel at i vely

less profitable borrowers (firms in the L regime) at the expense of the more profitable bor-

rowers (firms in the H regime) is a key prediction of our model.

We conclud e this section with a parent h et i ca l remark: While in our baseline mod el we

have treated the population of firms as fixed, an extension of the model to allow for firm

entry wo u l d readily im p l y that new firm creation is impeded when the economy is in a crisis.

Since banks earn rents on their loans to h i g h -p r ofi t a b i l i ty firms, this means that a smaller

surplus would be left for aspiri n g entrepreneurs, who could create firms that start out i n the

H regime and have to rely on ban k financin g . Accordingly, firm-creat i on incentives would

be weaker, along with aggregate investment and growth.

12

2.3 Empirical implications

The next proposition contai n s a testable prediction of the model:

Proposition 3. During the crisis state,

R

L,c

− R

H,c

ρ (1 − C

∗

)

< 1. (15)

The interpretation of Proposition 3 is that comparing a firm in regime L and a firm in

regime H , the difference in interest rates, R

L,c

− R

H,c

, is smaller than the difference in the

i

nstanta n eou s expected loss upon default, ρ (1 − C

∗

) — a manifestation of the rents that we

discussed above.

If firms are heterogeneous and each firm is charged a different value of R

H,c

i

and R

L,c

i

,

r

elation (15) imp l i es

E

i

R

L,c

i

− R

H,c

i

ρ (1 − C

∗

)

=

E

i

R

L,c

i

− E

i

R

H,c

i

ρ (1 − C

∗

)

< 1, (16)

where E

i

is a cross-sectional expectation . Equation (16) can be written as

E

i

R

L,c

i

= E

i

R

H,c

i

+ β

ρ (1 − C

∗

) , where β < 1. (17)

In other words, we should expect a beta coefficient less than 1 in a cross-sectional regression

of R

i

on the (in sta ntaneous) expected ca p i t al loss in t h e case of de

fault, which would be the

marginal cost of the loan in a frictionless market.

10,11

We refer to this model prediction as

t

he “limited pass-t hr o u gh ” hypothesis and test it in section 5.

An additional theoretical implication of th e model is that pass-through is not only limited,

but is also “asymmetric” in a sense that we explain next. In our model, the pricing of the

loan in the H regime is determined by V

H,c

=

D

C

, which ensures a borrower is not poached

by a rival bank. By contrast, in the L regime, th e pri ci n g of a loan is determined exclu si vely

10

In our stylized model, during the crisis regime, this expected loss is zero if t h e fi r m is in the high-

profitability regime H and ρ(1 − C

∗

) if the firm is in the low-profitability regime L.

11

We also note that in the data, the relevant default probability is not ju st the instantaneous default

probability, but rat h er the default probability over the duration of the loan. Therefore, the theoretical

conclusions of our model should be understood as approximations for loans that are sufficiently short term.

13

by a borrower’s ab i l i ty to pay, R

L,c

i

= π

L

.

To show the empirical implications of this asymmetry, one can extend th e model to

introduce borrower-specific regime switches in the parameters governing the cash-flow dy-

namics o f each borrower (e.g., Markov regime shifts in p

L

or p

H

) that are independent of

t

he cash -fl ow regime switches we have d i scu ssed so far. The goal of this extension is to

allow wit h i n -borrower and within-profitab i li ty-regime variation in the interest rate o f each

borrower.

Now consider a borrower in the H regime and suppose the borrower becomes riskier (e.g. ,

p

L

jumps up for that borrower). According to (13), this change will increase R

H,c

.

12

It will

a

lso increase the probability of default of a loan that is extended over a discrete interval of

time.

13

Therefore, fixing a firm tha t is in regime H,

we should observe a posit i ve within-firm,

within-regime co-variation in the inter est ra t e and the d i scret e-i nterval probability of default.

By contrast, if a firm is in the L regime, changes in p

L

or p

H

will change the discrete-interval

p

robability of default but will leave interest r a tes unaffected (because the interest rate is

determined only by what the borr ower can afford to pay, R

L,c

i

= π

L

). This implies a zero

c

ovariance between interest rates and the discrete-interval probability of defa u l t for firms in

the L-regime. This “asymmetric” pass-th r ou g h implication is an additional feat u r e of the

model and we test it in sectio n 6.

3 Regulatory Framework and Data

3.1 The Greek financial crisis

T

he global financial crisis of 200 8 and the subsequent European sovereign crisis had

a severe impact on the Greek economy. In just a few years, Greece lost over 25% of its

GDP, and its unemp l oyment rate reached 27%. Greek bond spreads climbed higher than

1,000 basis points (bp s) , thus (de facto) exclud i n g the cou ntry from international ma r kets.

12

Note the value function V

H,c

=

D

C

is irrespective of any parameters, and so the regi me switches i n the

parameter p

L

will only impact R

H,c

, not the value functions V

H,c

, V

L,c

.

13

Note t hat whereas the inst antaneous probabi l i ty of default is zero for a firm in the profitability regime

H (as long as the economy remains in the cr isi s state), the probability of default over a discrete interval of

time (e.g., t to t + 1) is always positive and increasing in p

L

. The reason is that the probability that the

firm could go into regime L and then into default over the time-interval t to t + 1 is positive.

14

The recovery process was particularly prolonged and required three eco m o m i c adjustment

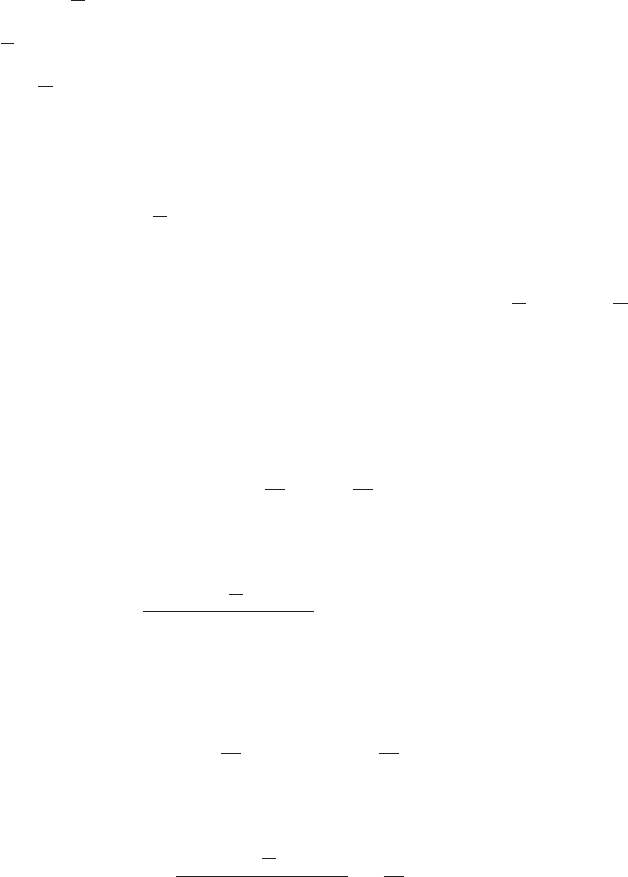

programs (Memorandum of Understan d i n g ( Mo U)) —i n 2010, 2012 and 2015. Fig u re 1 plo ts

Greece’s (real) gdp growth r ate and compares it with Cypr us, Italy, Portugal, a n d Spain

(CIPS) over the period covered by our d at a set. The main poli ti cal event, the election of

the anti-austerity party of Syriza, is depicted with a dotted line. Figure 1 shows that Greece

e

xperiences negative, or very weak, positive growth rates for essentially our entire sa m p l e

period. Unlike the other CIPS countries, Greece did not experience a recovery from 2014

onwards.

The crisis had an acute im p a ct on t h e banking sector, which has al ways played a central

role in the Gr eek financial system.

14

The crisis exposed long-term weaknesses of the banking

s

ector, including t h e over-exposure to Greek government bonds. The “p r i vate sector i nvolv-

ment” (PSI) restructuring program and the significant “haircut” on Greek bonds in 2012 led

to the first recapitalization of the four major (“systemic”) Greek banks mainly with pub l i c

funds. Two additional rounds of recapitalization were necessary in 2014 and—after capital

control s were imposed—i n 2015.

This setting motivates the two key assumptions of our model during the “crisis” period

(which corresponds to the entirety of our sam p l e) , nam el y, (i) collapsing co l l a ter a l values and

(ii) limited access to international cap i ta l markets. Fo r instan ce, the Bank of Greece reports

a 30% decrease in commercial real -est a te values from 2010 to 2014, a conservative proxy

that banks use to track collateral values o f corporate loa n s.

15

Furthermore, Greece remained

p

ractically excluded from international financial markets until 2017, and the Gr eek banking

system became increasingl y reli a nt on ECB and emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) funds.

3.2 Regulatory framework: The new loan pricing guidelines

Before the crisis, corporate loan managers u sed to base their pri ci n g decisions on bank

funding and operating costs, as well as an i nternal credit-risk assessment of the borrower.

These managers, who typically maintain a po rt fo l i o of a l i m i t ed number of firms, were

14

For an excellent review of the Greek financial system during the period of the Greek crisis, see Haliassos,

Hardouvelis, Tsoutsoura & Vayanos (2017).

15

ht t ps: //www. ban kofgreece.gr/en/statistics/real-estate-market/resid

ent i al-an d -commerci al -pr operty-

price-indices-and-other-short-term-indices

15

responsible for negotiating with the borrowers and final i zi n g the term s o f new loans, subject

to approval by the upper-level management of the bank. Although ba n k funding costs, and

interna l credit assessments were taken into consideration i n setting the interest rate on a

loan, no systematic, data-driven, and model-based determi n at i o n of the margin a l cost of a

loan (th e breakeven rate) was in place that bank ma n ag er s had to charge, leaving significant

room for di scr et i on .

Followi n g the PSI, which led to a significant “haircut” on Greek bonds and the inevitable

recapitalization of Greek b a n k s in 201 2, the monitoring trustees

16

required the development

a

nd use of uniform, data-driven, pricing mod el s for credit products. Th i s request reflected

growing concerns over subjective pricing and zombie-lending practices, not only in Greece

but in a number of countries on the periphery of Eurozone (e.g., Acharya, Imbierowicz,

S

teffen & Teichmann (2020); Acharya et al. (2019)).

In response to these mandates, each major syst em i c ba n k had to gradually develop its own

pricing model , independently. However, all frameworks had to adhere to two requirements.

First, they should be based on exogenous credit -ri sk assessments to ensure banks could

not affect the underlying credit risk models. Second, the pricing models should be applied

uniformly to all firms of the same class (in our case, the large corpo r at e portfolio) with

common p ar a met ers for non-firm-specific variables. Importantly, regulatory charges would

no longer be computed directly at the level of the b a n k ’ s entire portfolio, but rather at the

individual loan l evel and then aggregated. The goal was to create transparency about the

marginal contribution of each loan to the b a nk ’ s regulatory capital charges.

The p r i ci n g model of the bank that we consider has a “fixed” and a “variable” (i.e.,

loan-specific) component. The fixed component includes the bank’s fund i n g and operati n g

costs, which are common for all firms in our sample. Th e bank uses long-term p r ed i ct ion s for

these costs; therefore, these components do not vary either in the cross-section or the t i m es-

series dimension in our sample. The variable component is loan-specific and depends on loa n

and bo r rower chara cter i st i cs. Because the majority of loans in our sample are floating-rate

products, i nterest-rate risk adjustments a r e negligible in the cross-section, and the main

16

Monitoring tr u stees refer to auditing companies, which work under the direction of th e European Com-

mission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund, and audit all activities of Greek

banks following the P SI.

16

source of cross-sectional vari at i o n is due to credit r i sk .

Followi n g contempo r ar y bankin g practice, the credit-risk cost consists of the cost for “ex-

pected losses” and the cost for regulatory capital. The cost for expected losses is estimated

based on the di fferen ce between the loan bal a n ce and the adjusted value of the collateral

multi p l i ed by a formulaically-derived default probability for the firm. This default prob-

ability is based on a credit model developed by an entity outside the b a n k. The cost of

regulatory capital, which is related to “unexpected losses,” is estimated using a credit-risk

model in accor d a n ce with the Basel framework a s defined in regulation EU 575/2013 (Cap-

ital Requ i r em ents Regulation - CRR), adjusted by a hurdle rate. Note that all the inputs

into the credit-risk cost a r e based on models, which in turn use company balance-sheet data

as inputs.

The fixed and the variable components, descr i bed above, ad d u p t o t h e br eakeven interest

rate, which is the fin a l output of the pricing model. The guidelines to the loan managers

describe the breakeven interest rate as t h e lowest i nterest rate that does not rend er the loan

loss-making – in effect, the marginal cost of the loan. Loan managers are free to offer rates

higher than the breakeven rate to their borrowers. But if the actual rate is lower than the

breakeven rate, the monitoring trustee requ i r es internal approval at the highest level, which

states the reason for t h e discount.

3.3 Data

Our a n al y si s combines several proprietary datasets from a large Greek bank, whi ch we

combine using coded identifiers at the borrower and a ccou nt (i.e. , loan) level . Our main

sample comprises all loans extended to firms that belong to the “large corporate portfolio”

of the bank (hereafter, large firms). The large corporat e portfolio of t h e b an k consists of

firms above a certain si ze threshold. Our main sample consists of 1625 accounts and 15 0

borrowers, and includes some of the la rg est (top 5% in terms of assets and sales) and most

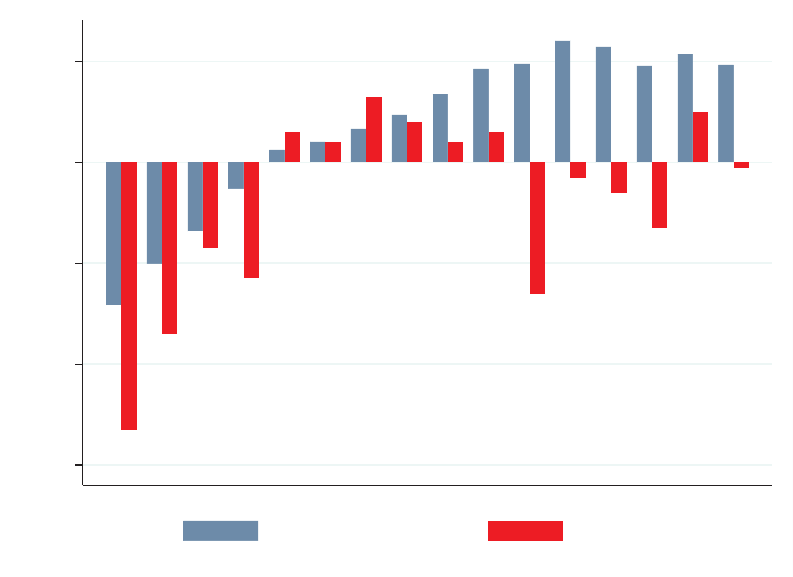

established firms in Greece. Figure 2 repo rt s the distributio n of log(assets) for the 150 firms

t

hat constitute our sample as well as the universe of Greek firms covered by Am ad eu s van

17

Dijk database in 2014.

17

As is evident from th e graph, our sample covers the largest fir m s

in Greece.

We focus on term loans and credit lines, and our sample period extends from January

2015 to June 2017. In section 4, we also extend our dataset back to January 2013 to study

t

he pricing p r act i ces of the bank prior to the introduction of the new loan-pricin g guidelines.

Our main dataset provi d es information on new loan cont ra ct s during our sa m p l e period.

Every time a new loan i s extended to a firm, we o b ser ve both the actual and the breakeven

interest rate. We also observe the values of the components of the breakeven rate as well as

the variables used for the estimation of each component (i.e., cred i t score, collateral). Over

the course of our sample, sh or t -t erm loans commonly come up for renewal; thus, we typically

observe several loan contracts per borrower.

As noted i n section 3.2, loans that are priced below the breakeven rate requ ir e specia

l

approval and a justification for the discount. In a separate file, we observe all the internal-

approval decisions for loans priced below the breakeven rate, along with the provided ex-

planations for the discount. These justifications are qualitative, but a discrete number of

categories exist that each justification can fall into.

Moreover, we ob ser ve t h e performance of past and new loans of ever y fi r m a t a mo nthly

frequency. The data contain information on monthly payments, amounts outstanding, credit-

line utilization , credit scores, past-due days, and the borrower’s status. Finally, we comple-

ment the d a t a with firm-level accounting info r mat i o n from firms’ balance sheets and annual

income statements.

3.4 Summary Statistics

Table 1 reports summary statisti cs for our sample. Panel A focuses on

loan-level variables

and shows that theaverage actual interest rate and breakeven i nterest rate in our sample are

5.4% and 4.8%, respectively, implying an average markup (which we define as the difference

between actual and breakeven interest rate) of 62 bps. Remarkable differences exist in

the markups charg ed to different loans. At the 5th percentile, the markup is significantly

17

Amadeus Bureau van Dijk database is a comprehensive, pan-European database containing financial

information on over 14 million public and private companies.

18

negative (-3.57%), whereas it is very large at the top 95 t h percentile (4.46%).

The average loan b a l an ce is 3. 6 million euros, but with a substantial standard deviation

(14.35). The average maturity is short (0.62 years) and its standa rd deviation is compar -

atively large (standard devia t i on of 1 . 51 ) . The short average maturity is to be expected,

because short-term loans tend to be rolled over more frequently than long-term loans, thus

making up a bigger fraction of the observations. In ad d i ti o n , because our dataset corresponds

to a crisis period, the b a n k prefers the flexibili ty of short-term loans that get rolled over fre-

quently. (This featu re of the data is what motivated us to abstract from long-term debt

contracts in our model and instead focus on continuously rolled-over loans). The majority

of the loans are collateralized (85% of the loans have collateral.) In the Appendix (Tables

A3 and A4), we p r ovide the summary stat i st i cs for term loans and credit

line products

separately.

We present the summary statistics for borrower-level variables in Panel B of Table 1. The

a

verage borrower in our samp l e has operating returns on asset s (OROA) of 4.6%, deposits

of 19 million euros, total assets of 238 million euros, and l i a b i l i t i es equalling 51% of their

assets.

4 Introduction of the New Pricing Guidelines

In this section, we ask two questions. First, did the adoption o

f the new pricing guidelines

have a material impact on the interest rates faced by borrowers? And secon d , d i d the

variables that matter for the loan-pricing decisions change after the new pricing framework

was enacted?

We start by showing that the adoption of the new pricing guidelines had a material

impact on loan-pr i ci n g decisions.

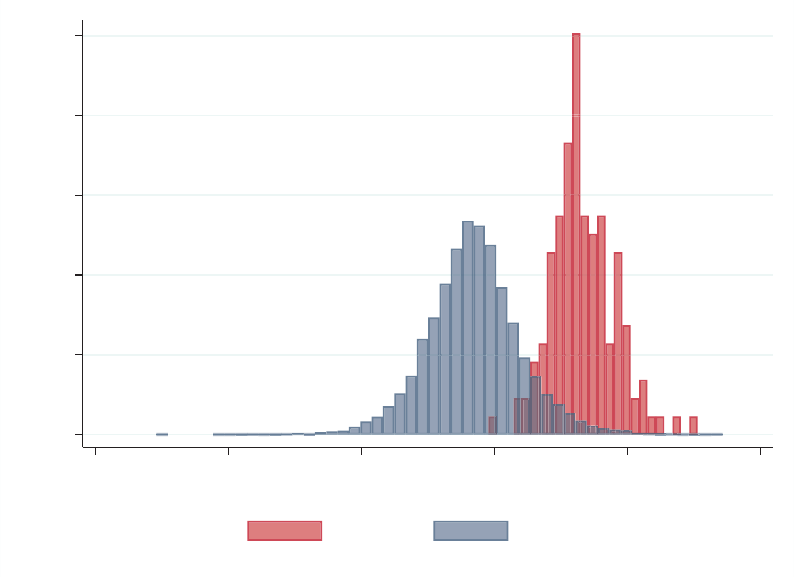

To illustrate the effects of the enactment of the new pricing guidelines, we sort borrow-

ers into three terciles (low, medium, high) according to the initial breakeven interest rate

provid ed by the new pricing model, that is, their first-ever assigned breakeven interest rate.

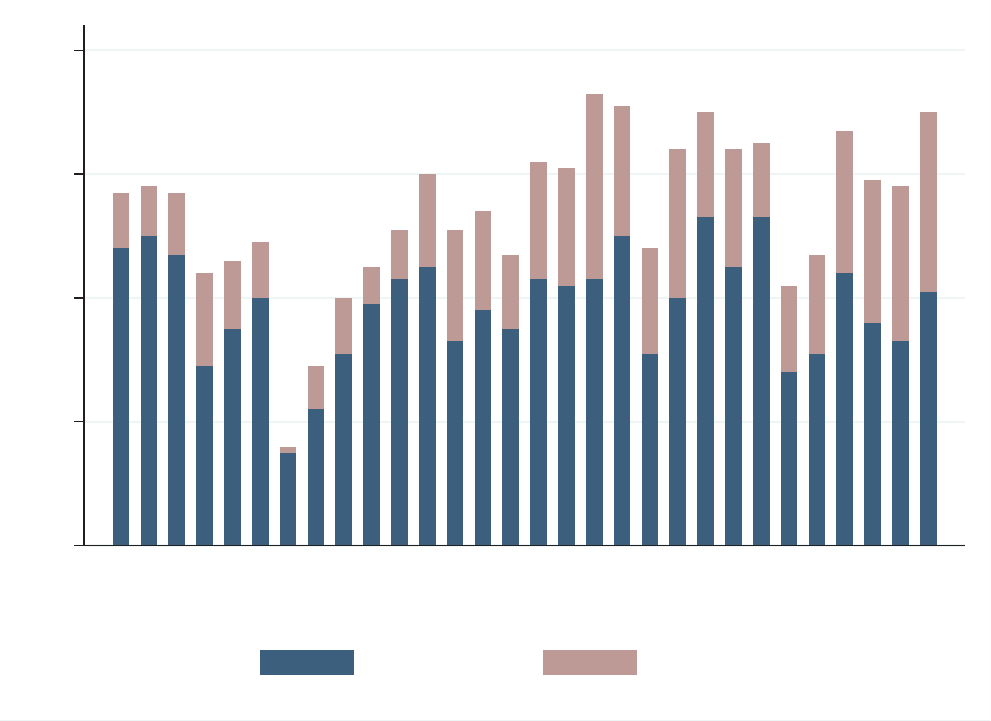

Figure 3 presents the average interest rate charged on new loans for ea

ch of the three

groups by month over our entire sample. The graph illustrates a discrete change in the

19

actual interest rates char ged to the three grou p s upon the introduction of the new pricing

guidelines. First, we observe that prior to the enactment of the new pricing guideli n es,

no major differences exist in the interest rates char ged to th e three gr ou p s. Thereafter, a

visible divergence occurs a cr oss the three groups, with high-breakeven-rate borrowers facing

substant i a l l y higher interest rates, borrowers in the middle group showing no appreciabl e

change, and borrowers in the low-break-even-rate group obtaining somewhat lower interest

rates than before. Interestingly, durin g the two turbulent months surrounding the imposition

of capital controls (mid-2015), we find that interest rates across all three groups temporarily

converge back together. This ob ser vation suggests that at the tim e when the Greek financial

crisis reaches its cli m a x ,

18

evidence shows that t h e pricing model is de-facto temporaril

y

suspended. However, this pheno m en on only lasts until Greece sig n s a new MoU wi t h its

creditors. Thereafter, the differences between the three groups r evert to the levels seen

around the intro d u ct i on of the new pricing guidelines.

To further study the effect of the introduction of the new pr i ci n g guidelin es in 2015,

we restrict our sample to borrowers who sign a new loan contract wi t h the bank both in

the year prior to the introduction of the new pricing guidelines and in the year of the

introduction, to account for any changes in sample composition between those two years.

19

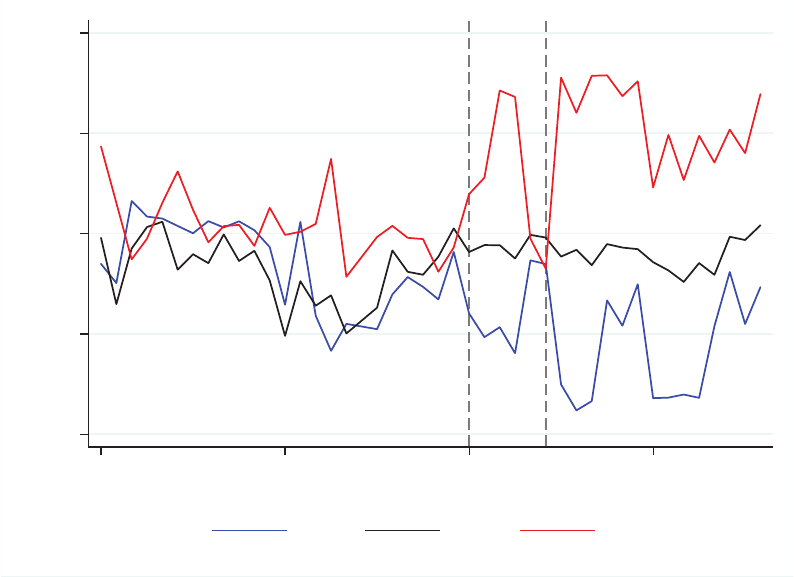

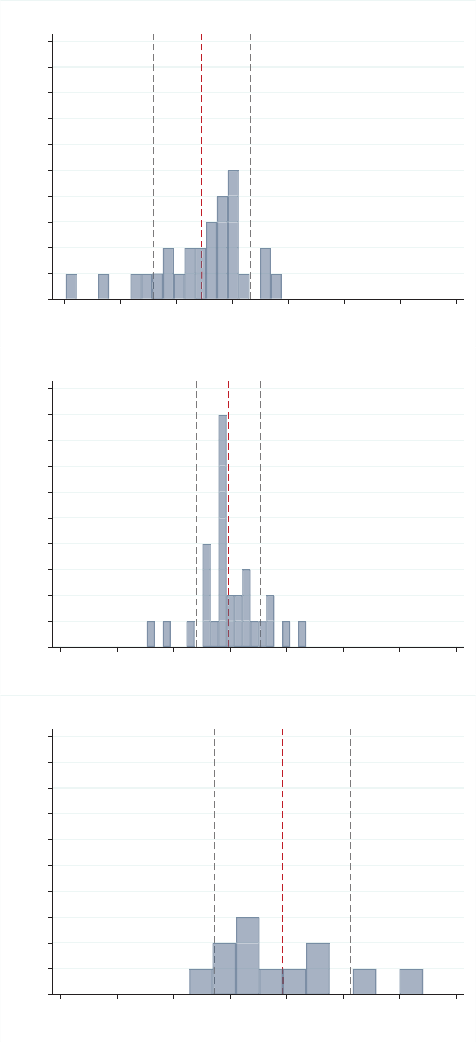

In Figure 4, we report the distributi o n of the change i

n each borrower’s inter est rate between

the year before and after the introduction of the new pricing guidel i n es. We then plot the

distribution of these differences by initi al -b r ea keven-rate group. We find these distribution s

indeed appear different for the three groups. The borrowers in the low-initial-breakeven-

rate bin receive a favorable adjustm ent t o their interest rate (1 . 0 8% decrease on average),

whereas the high initial-breakeven-rate borrowers receive an unfavorable adjustment (1.86%

increase on average). On average, the medium -in i t i a l -b rea keven-rate borrowers experience no

interest r a te adjustment. We further fin d that the three groups’ distrib u t i on s are statistically

significantly different according to (pairwise) Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests.

18

During those two months, the financial situ at i on of the country can be fairly described as bordering on

chaot i c, with banks imposing strict withdrawal limits on individuals and inter nat i onal capital fl ows permitted

only for absolutely necessary, trade-related reasons. Esp eci all y durin g the few weeks between the referendum

of June 2015 and th e signing of the new MoU with the monitoring institutions, wh et her Greece was going

to remain in the Eurozone was unclear.

19

We treat renewals of old loans as new loan contracts, because the bank does not distinguish between

them and assigns a new loan identification number, reflecting that a loan renewal is a new legal contr act .

20

Additionally, we perform a reg ressi o n analysis to test the relationshi p between a bor-

rower’s initial breakeven rate and th e change in their actual interest rate on new loans.

Similar to Figure 4, the sample co n si st s of borrowers who sign a new loan contract with the

bank both in the years pre- and post-gu i d el i n e introduction. Specifically, we estimate th e

followin g specificat i o n :

∆Actual Rate

i,2

015

= α

s

+ β(Br e akeven

i,2015

− Actual Rate

i,2014

) + δ∆X

i,2015

+ ε

i

, (18)

where Actual Rate

i,t

is the average interest rate for new loans in year t f

or borrower i (and

∆Actual Rate

i,2015

is the difference between the average interest rate in years 2015 and

2014 for that borr ower), Breakeven

i,2

015

is the average breakeven r a t e for borrower i in t h e

year 201 5, α

s

are industry fixed effects, and ∆X

i,2015

are first differences in some borrower

control s. Intu i ti vely, we regress the change in the borrower’s interest rat e from 2014 to 2015

on the difference between the borrower’s 2014 interest rate and their initial breakeven rate

prescribed in 2015. The coefficient of i nterest β captures how many basis points the actual

rate of the borrower moves, for a 1 bps difference between the initi a l breakeven rate and the

actual rate in 2014.

We also report results for a similar specification, using an adjustment model wit h “iner-

tia”:

Actual Rate

i,2

015

= α

s

+ βBre akeven

i,2015

+ ρActual Rate

i,2014

+ X

i,2015

δ + ε

i

. (19)

We note specifi ca t i on (19) nests (18) as a special case, when ρ =

1 − β.

20

Table 2 pr esents the results of equations (18) (Panel A) and (19) (Panel B). It shows

that the introduction of the n ew pri cin g model h a s a significant effect on the bank’s prici n g

policies. The estimated β in colum n (1) of Pan el A is 0.4 implying that for every 1%

discrepancy between the initial breakeven rate and the prior year’s actual rate, the interest

rate cha r ged to the borrower rises by 40 bps. This result is both economically and statistically

significant. Columns (2) and (3) further show that the result is similar in magni t u d e when

we add borrower-level ch ar a ct eri st i cs, or industry fixed-effects. In Panel B, the β estimates of

20

This follows from ∆Actual Ra te

i,2015

= Actual Rate

i,2015

− Actual Rate

i,2014

.

21

equation (19 ) remain essentially uncha n ged when we include a control for the actual inter est

rate in the year 2014 (i.e. , before the enactment of t h e new pricing guidelines).

As an additional illustrat i on of how the intr oduction of the new pricing guidelin es changed

the bank’s pricing behavior, we perform the following exercise: using the borrower credit

rating and the formulas used to compu te the breakeven rate according to the ban k ’ s model,

we can comp u t e what the breakeven rate would have been for each borrower for th e years

prior to the introduction of the new pricing g u i d el i n es. Of cou r se, this inform at i o n was not

available to loan managers at the ti m e.

Table 3 a n d Figure A2 (in the appendix) show that the (ex-post calculated) breakev

en

rate plays essentially no r ol e in loan-pricing decisions pr i or to the enact m ent of the new

pricing guidelines, but plays a dominant rol e thereafter.

Figure A2 provid es a visua l il l u str a t i on , by showing a scatter plot of a

ctual and breakeven

rates for the four quarters prior to the int r oduction of the new pricing guidelines and the

four quarters after. The figure shows essentially no r el a t i on between the breakeven rate and

the actual rate prior to the introduction of the new pricing guidelines and a clear positive

relation after. In the next section, we ex am i n e this positive relation in greater detail.

Table 3 formalizes this visual impression in a regression framework.

The table shows that

by creating a transpa rent, loan-level measure of marginal cost, the new pricing guidelines

mitigated non-economic influences on loan prici n g . To illustrate, we use various data on

board characterist i cs of the fir m s in our sam p l e, which are descri bed in the Appendix (Table

A1). These board characteristics are intended to capture polit

ical and media affiliations of

board members, and tightly-held family firms (which would indicate a higher likelihood of

personal con n ect i o n s), and so on. We then run reg ressi o n s of actual loan rates on the re-

spective breakeven rates (whi ch we calculate ex-post for 2013 and 2014) a l on g with variables

reflecting board characteristics. We contr ast the data p r i o r t o t h e en act m ent of the new

pricing guidelines and ther eaft er . Becau se we have several variables on board char act er i s-

tics, we r u n a lasso regression to determine which variables have explanatory power before

and after the enactment.

Table 3 reports the results of OLS and lasso regressions. Column (1) of

Table 3 shows

that the (ex-post calculated) breakeven rate cannot exp l a i n the actual interest rate during

22

the pre-gu i d el i n e period. Meanwhile, many board-characteristic variables (e. g . , having the

firm founder on the board, or having a board memb er with political affili a t i on s) are sta-

tistically significant for ex p l a i n i n g the actual interest rate during the pre-guidelin e perio d .

Furthermore, column (2) shows that most of th e board-characteristic variables are included

in the restrictive set of covariates selected by the lasso regression. For example, variables

such as “politician on board” or “media executive on board” appear important during the

pre-guideline period. Columns (3) and (4) show a d r a sti c change after the enactment of the

new pricing guidelines. Specifically, column (3) shows that thebreakeven rate is one of only

two variables with statistical sign i fi ca n ce in the full-covariate OLS specification. Interest-

ingly, we find that the breakeven rate is the only variable selected by the Lasso regression

in column (4), suggesting that aft er the ad o p ti o n o f the new pr i ci n g gui d el i n es, the board-

character i sti c variables lose their ability to predict the actual interest rate charged on loans.

This stark contrast illustra t es that the new p ri ci n g guidelines reduced the discretion that

was afforded to loan managers by the lack of a tran sp a rent, loan-level breakeven rate.

In su m m a r y, this section showed that the intr oduction of the new pricing guidelines had

a material impact on loan p r i ci n g. By creating a tr a n sp ar ent, loan-level measure of marginal

cost, the new gui d eli n es appea r to have mitigat ed non-economic influences on loan-pricing

decisions. Ta b l e 3 sugg ests that the board variables that seemed to play a rol e du

ring the

pre-guideline period for the determinat i o n of loan rates appea r to play n o role thereafter.

The next section focuses on the p o st -gu i d el i n e period and shows that although the new

pricing guidelines had a material impact on loan negotiations, the regression coefficient (“pass

through”) from br ea keven rates to actual rates is far below one.

5 Limited “Pass Through”

In th i s section, we test the cross-sectional implication s of Pr

oposition 3. We focus on the

dates a ft er the implementation of the new pri ci n g guidelines and investigate one of the key

predictions of our model, namely, that less than a one-for-one “pass t h r o u gh ” exists from

the breakeven rate to the actual rat e. Phrased in a mathematically equivalent way, we test

whether the “markup” (the difference between the actual and breakeven interest rate) is a

23

decreasing function o f the breakeven rate.

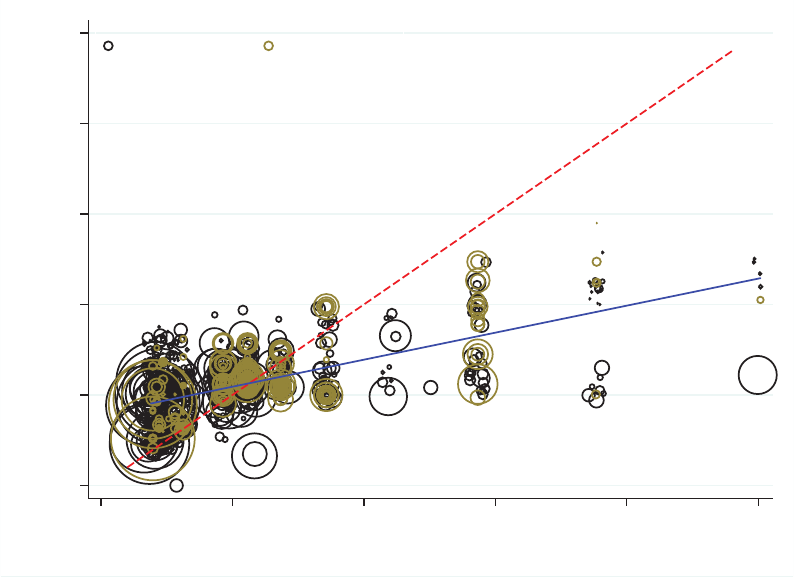

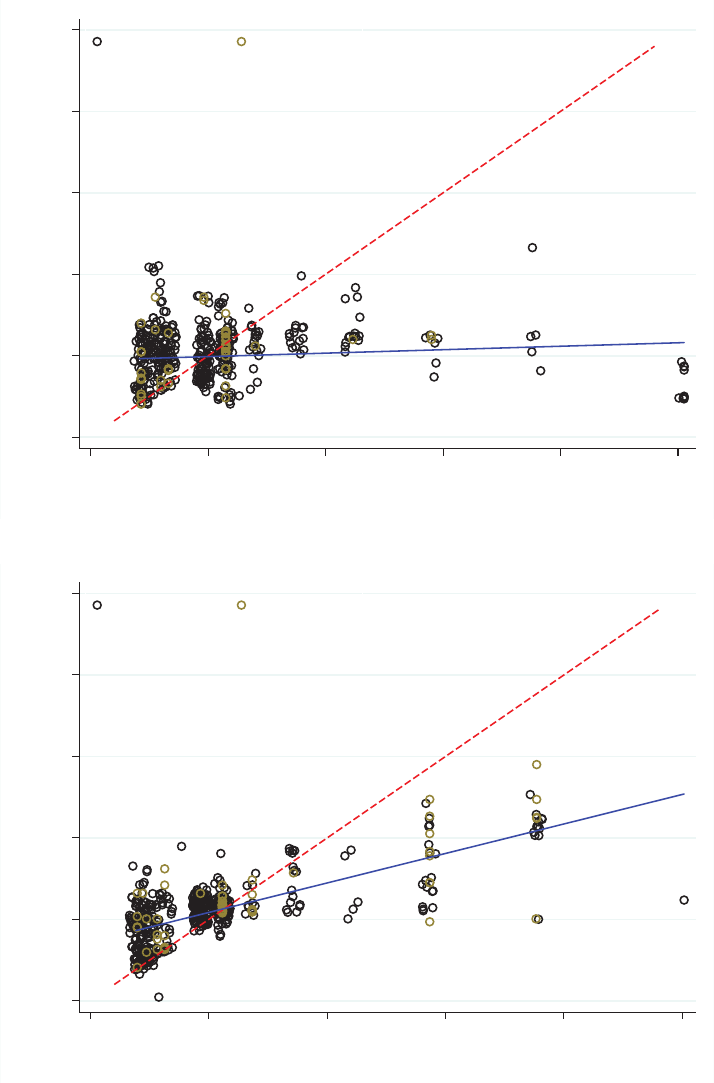

Figure 5 provides a first illustration of the relat i on between the brea keven and act u a l

rate for all loans initiated during the post -g u i d el i n e period. An observation above the 45

◦

line indicates a loan priced a bove its breakeven rate, wherea

s an observation b el ow the 45

◦

line indicates a loan priced below its breakeven rate. Some observations have the same x-

value, because the borrower’s credit rat i n g , which is an input into the prici n g equation, takes

discrete values.

A few observations about Figu r e 5 are n o teworthy. First, the large majority of the

o

bservations are above the 45

◦

degree line, consistent with the pricing guidelines provid ed

to the loan managers. Additionally a small, but non-trivial number of l o a n s receive act u a l

rates bel ow the b r eakeven rate, even t hou g h such loans are scrutinized and r eq u i r e internal

approval, as we di scu ss in greater detail in section 7.3. The slope of the regression line

r

elating actual and breakeven rates is substantially less than on e, implying t h a t the markup

(the difference between the actual and breakeven rate) is a declining function of the breakeven

rate.

To gauge the statistical significance of the pattern illustrated in Figure 5 and to control

f

or covariates, we estimate the following OLS specification:

Actual Rate

imt

= α

t

+ α

s

+ β

Breakeven Rate

imt

+ X

it

δ + X

m

η + ε

imt

, (20)

where Actual Rate

imt

corresponds to the int er est rate issued to l oan m o

f borrower i, and

month t, α

t

are time fixed effects, α

s

are indu st r y fixed effects, X

it

are time-varying borrower

c

ontrol s, an d X

m

are loan controls. The coefficient β of Breakeven Rate, which represents

the cross-sectional pass-through of the breakeven interest rate, is our mai n est i m at e of in -

terest. Specifically, values below one signify that each percentage increase in the breakeven

rate results in a l ess than one-for-one pass-through to th e actual interest rate.

We report our baseli n e estimates of equation (20) in Table 4. The estimated β c

oefficient

of the breakeven rate in column ( 1 ) is roughly 0.3, meaning a 1% increase in the breakeven

rate results in a 30 bps increase in the actual interest rate. In colu m n (2), we show that this

relationship is unchanged after including time (quarter) fixed effects. Columns (3) to (5)

24

show that the estimate of cross-sectional pass-throu g h is unaffected when including observ-

able firm-level characteristics, loan-level characteristics, or industry fixed effects. Including

these covar i at es leaves the estimat e and the standard errors of the breakeven rate essentially

unchan ged . In part i cu l ar , controlling for the breakeven rate, firm-performan ce indicators

such as OROA, or the ratio of Assets-to-Liabiliti es do not play a sign i fi ca nt role.

Column (6) augments equation (20) with firm fi x ed effects and shows that the pass-

t

hrough from breakeven to actual interest rate is significantly reduced once we account for

firm-fixed effects. We postpon e a detailed discussion of this finding until section 6.

T

able 5 revisits the regressi o n s of Table 4 but i n clu d i n g a control fo r a borrower’s la gg ed

interest rate. This lag term is calculated as the average interest rate of the borrower’s loans in

the most recent p r evi ou s m o nth, and thus plausibly reflects up-to-date infor m at i o n th a t m ay

not be captured by the borrower-level controls. The table shows that even after controlling

for the lagged borrower-specific interest rate, our conclusions rema i n unchanged. In our

baseline specifications of columns (1) to (5), the coefficient for the breakeven interest rate

is statistically significant and ranges between 0.18 and 0.20. The observable firm-level and

loan-level characteristics do not exhibit significant expl a n at o r y power for the act u al interest

rate. However, the coefficient for the lag term of the borrower interest rate is statistically

significant and ranges between 0.54 and 0.58 in our baseline specifi cati o n s, which may be

either due to inertia in the interest-rate setting or to the fact that the lagged int erest rate

reflects more up-to-dat e information than borrower-level controls.

Finally, we find similar results for all the above tests when we separate the sample into

term loans and credit lines, which we r eport in the Appendix Tables A5 and A6.

6 Asymmetric Pass-Through at the Borrower Level

In thi s section, we test t h e model’s mechanism in greater detai

l. As we noted at the end

of section 2.3, on e important aspect of our model is that once a firm i s in the low-p r ofi ta b i l i ty

regime, the bank extracts al l free cash flow. I n this regime, the only determinant of the firm’s

interest rate is the firm’s ability to pay; the firm’s probab i l i ty of default becom es irrel evant.

By contrast, if the same firm finds itself in the high-profitabi l i ty regime, its interest rate is

25

determined by a limit-pricin g condition, and thus, the firm’s interest rate is positively related

to the firm’s default probability.

This fea t u re of the model can help explain why the regression coefficient in equation

(20) decreases significantly when we include firm fixed effects in th

e regression. To explain

why, we re-estimate equation (20) in cl u d i n g both time and firm fixed effects, but we split

the sample into two subsamples: th e first (second) subsample includes firms whose initial

breakeven rate at the introduction of n ew pricing guidelines is below (above) the median.

Phrased differently, the first (second) subsample contains borrowers who are likely to be in

the high- (low-) profitability regime in th e language of our model.

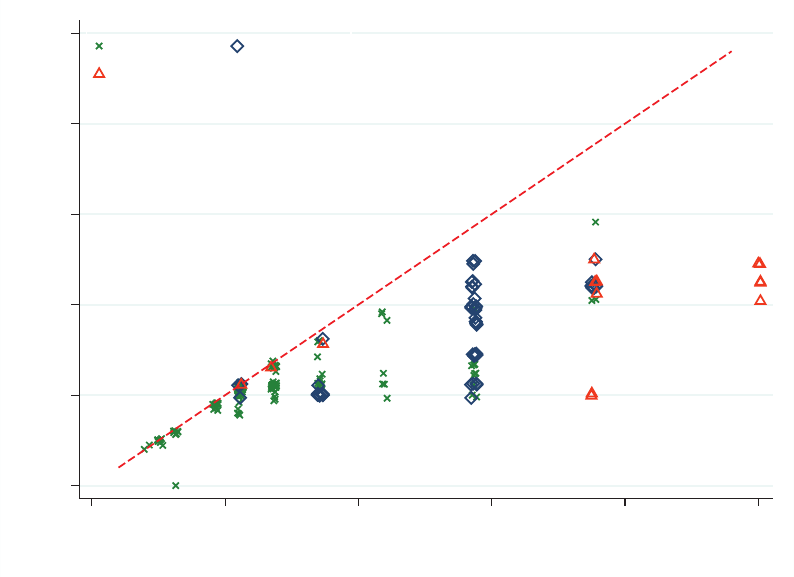

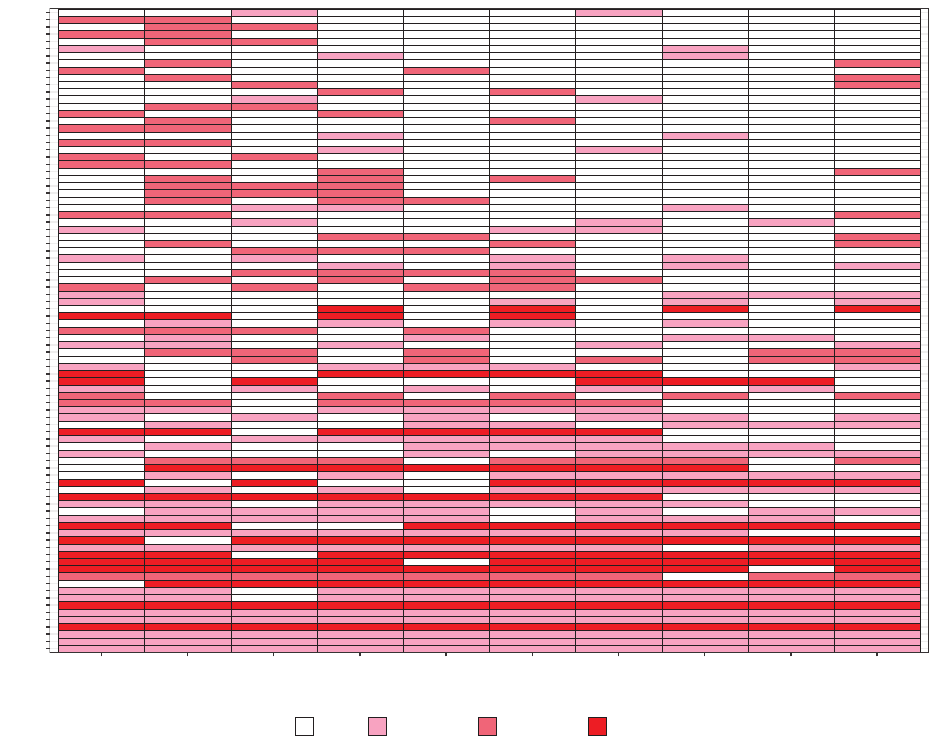

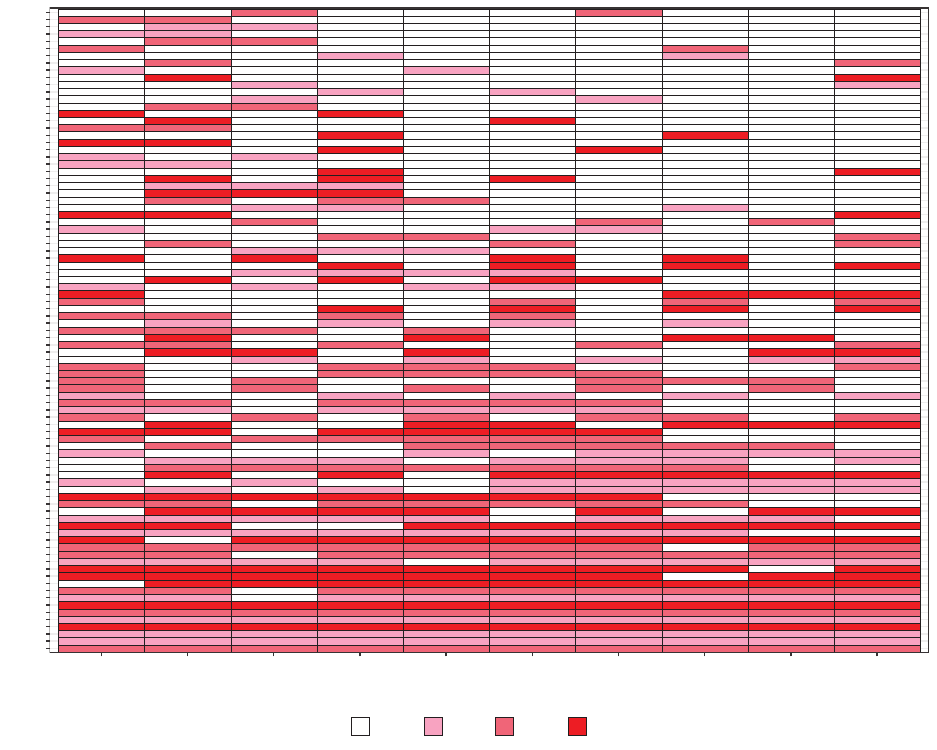

Table 6 reports an interesting asymmetry. Columns 3 and 4 show that th

e fi rm s with hig h

initial breakeven rates (risky creditors) exhibit essentially no pass-through after co ntrolling

for time and firm fixed effects.

By contrast, the firms with a below-median breakeven rate (safer creditors) experience

pass-through values around 0 . 43 , which are both economically and statistica l l y significant.

This finding is consistent with the view that after a certain value of the breakeven rate,

interest rates are dictated by factors such as the borrower’s ability to pay, rather than the

breakeven cost of the lo an – consistent with the predictions of the th eo ret i ca l model.

Because the pass-th ro u g h coefficient is essent i a l l y zero for below-break-even-rate borrow-

ers, the pass-th r o u gh coefficient for the entire sample becomes very small o n ce we control

for both t i m e and firm fixed effects.

The results of the previous and the current section can be summarized as follows. Upon

introduction of the new pricing guidelines, we observe a noticeable adjustment of loan rates

in response to the newly introduced breakeven rates. Thereafter, borrower-level changes to

the breakeven rate do not seem to pass through to th e borrower’s actual rate. However,

this muted pass-through (after including firm fixed effects) is driven by firms with high

initial breakeven rates. This finding is consistent with the view that (a) the ability of the

bank to charge high interest rates is constrained by the borrower’s ability to pay, and (b)

this constraint is more likely to be bi n d i n g for borrowers who st a r t out with hi gh initial

breakeven rates. Given that these borrowers are more likely to be in a regime where this

constraint is bin d i n g , incremental variations to their breakeven ra te are irr el evant for the

26

determination of t h ei r actual interest rate.

7 Discussion and Robustness

7.1 Superior inf or ma ti on and future ratings changes

O

ne possible interpretation of our results is that managers have superior information

about a borrower and view the breakeven rate as a noisy measure of the firm’s futu r e

prospects, thus choosing to not fully pass thro u gh the breakeven ra te to their borrowers.

For example, loan managers may choose to ignor e an increase in the breakeven rate if they

feel it presents a temporary worsening of the firm’s pro spects, which will revert in the fu-

ture. A testable implication of this view, simila r in spiri t to Chia p pori & Sala n i e (2000)

21

is

t

hat when the l oan managers charge an i nterest rate below the breakeven rate, this decision

should predict an improvement in the firm’s future creditworthiness.

In this section, we investigate whether the difference between actual and breakeven rate

has pred i ct i ve power for th e future prospect s of a firm. To test this alternative hypothesis, we

use the borrower “rating” as a dependent variable. The borrower “rating” has a on e-to-o n e

correspondence with the borrower’s probability of default, which in turn is the key input for

the determination of the breakeven rat e. The advantage of using the borrower rating is that

this quantity is always ava i l a b l e an d updated for each borrower, i r respective of whether the

borrower initiates a new loan contract in a g i ven month.

We run the following regression:

Rating

i,t+h

= α

t

+ α

s

+ φ

Diff

i,t

+ θ Rating

i,t

+ ε

i,t

, (21)

where Rating

i,t+h

corresponds to the rating of borrower i i

n month t + h, and Dif f

i,t

is

borrower’s i difference between the actual interest ra te minus the breakeven interest rate in

month t.

22

We include time fixed effects, α

t

, industry fixed effects, α

s

, and include a control

21

Chiappori & Salanie (2000) argue that a simple way to detect information asy mmetr i es is by testi

ng for

correlation between ex-ante choices and ex-post outcomes.

22

For borrowers wi t h multiple newly initiated loans in the same month, we compute the average difference

across these loans.

27

for the credit rating, Rating

i,t

, of borrower i in month t.

Column (1) of Table 7 presents the estimates of equat i on (21) using a ho r i zon of 12

months (h = 12). It sh ows that – controlling for a borrower’s current rating – Dif f has

no pr ed i cti ve ability for the borrower’s future credit rating. The coefficient φ for Diff

i,t

in (21) is both economically and st at i st i ca l l y insignificant. This fi

nding is consistent with

the si m p l e view that we took in our symmetric-information theoretical model, whereby the

regime transitions that determine the fir m’ s profitability and its probability of default are

simple Markov processes. Therefore, the differential between the actual and b r eakeven rate

has no further predictive ability, after controlling for the cu rr ent borrower rating. In columns

(2) and (3), we present the results for sampl es that include only the borrowers with a neg a ti ve