PRIVATE STUDENT

LOANS

Clarification from

CFPB Could Help

Ensure More

Consistent

Opportunities and

Treatment for

Borrowers

Report to Congressional Committees

May 2019

GAO-19-430

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-19-430, a report to

congressional c

ommittees

May 2019

PRIVATE STUDENT LOANS

Clarification

from CFPB Could Help Ensure More

Consistent

Opportunities and Treatment for

Borrow

ers

What GAO Found

The five largest banks that provide private student loans—student loans that are

not guaranteed by the federal government—told GAO that they do not offer

private student loan rehabilitation programs because few private student loan

borrowers are in default, and because they already offer existing repayment

programs to assist distressed borrowers. (Loan rehabilitation programs

described in the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection

Act (the Act) enable financial institutions to remove reported defaults from credit

reports after borrowers make a number of consecutive, on-time payments.)

Some nonbank private student loan lenders offer rehabilitation programs, but

others do not, because they believe the Act does not authorize them to do so.

Clarification of this matter by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

(CFPB)—which oversees credit reporting and nonbank lenders—could enable

more borrowers to participate in these programs or ensure that only eligible

entities offer them.

Private student loan rehabilitation programs are expected to pose minimal

additional risks to financial institutions. Private student loans compose a small

portion of most banks’ portfolios and have consistently low default rates. Banks

mitigate credit risks by requiring cosigners for almost all private student loans.

Rehabilitation programs are also unlikely to affect financial institutions’ ability to

make sound lending decisions, in part because the programs leave some

derogatory credit information—such as delinquencies leading to the default—in

the credit reports.

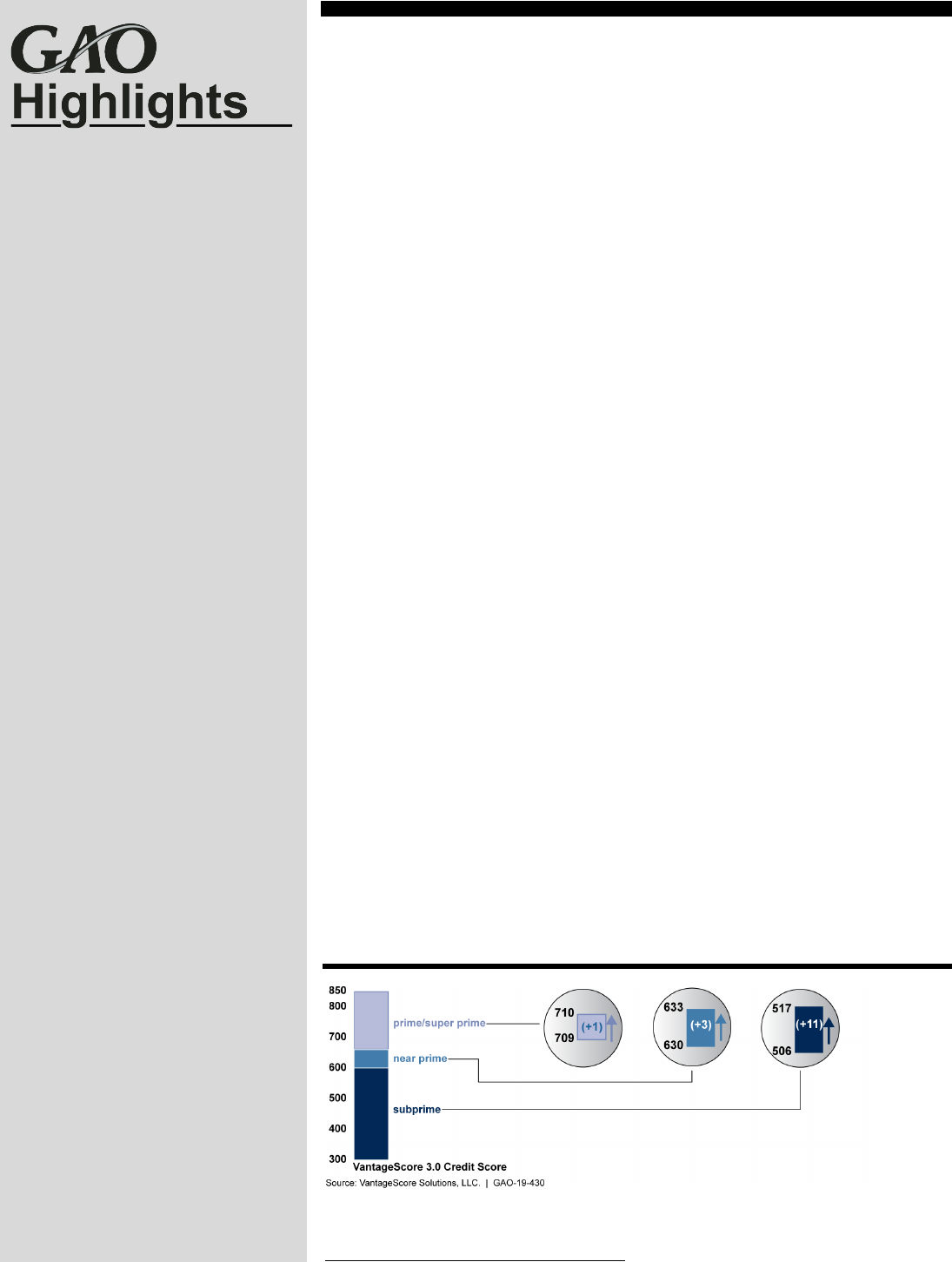

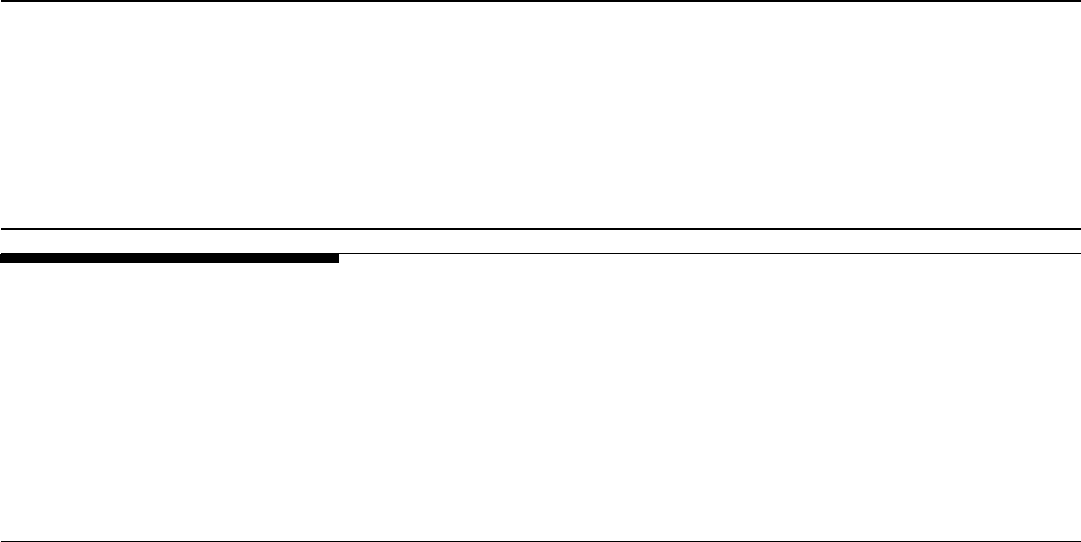

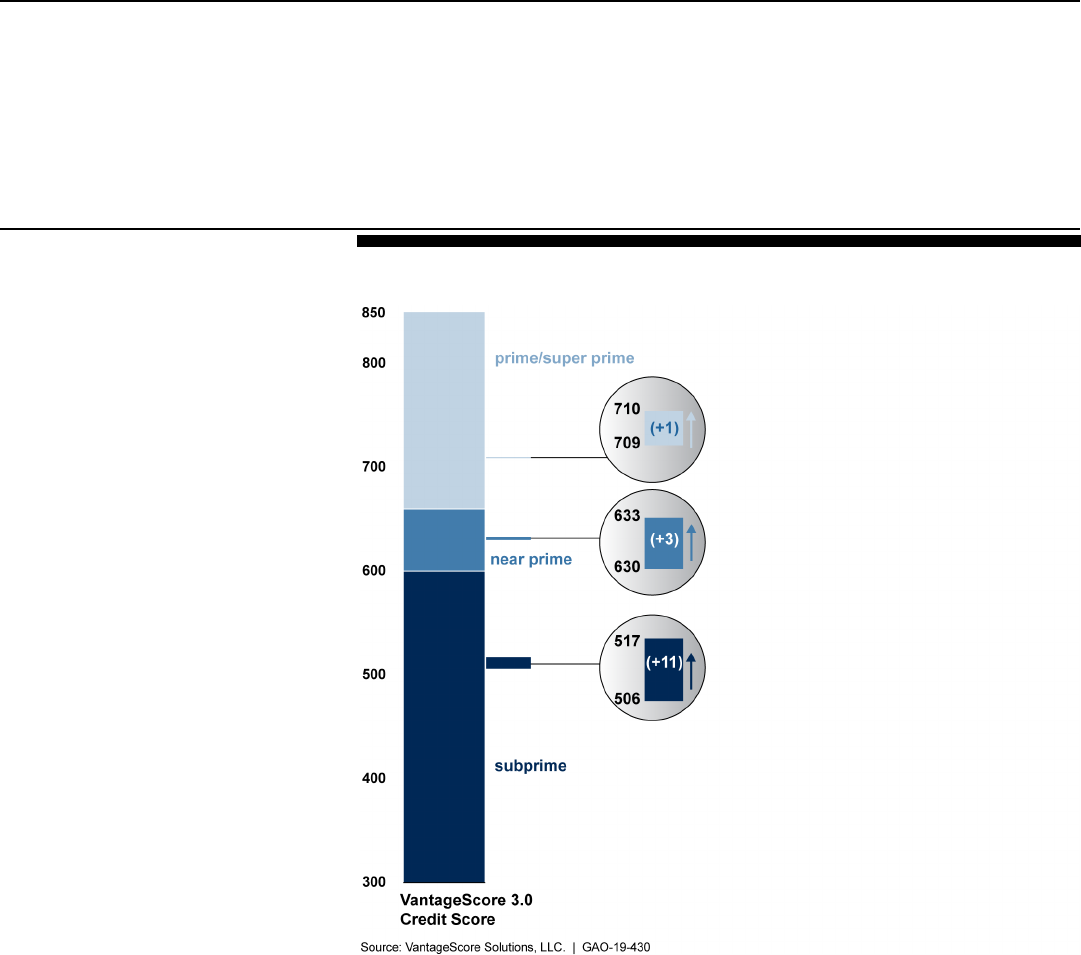

Borrowers completing private student loan rehabilitation programs would likely

experience minimal improvement in their access to credit. Removing a student

loan default from a credit profile would increase the borrower’s credit score by

only about 8 points, on average, according to a simulation that a credit scoring

firm conducted for GAO. The effect of removing the default was greater for

borrowers with lower credit scores and smaller for borrowers with higher credit

scores (see figure). Reasons that removing a student loan default could have

little effect on a credit score include that the delinquencies leading to that

default—which also negatively affect credit scores—remain in the credit report

and borrowers in default may already have poor credit.

Simulated Effects of Removing a Student Loan Default from Borrowers’ Credit Reports

Note: A VantageScore 3.0 credit score models a borrower’s credit risk based on elements such as

payment history and amounts owed on credit accounts. The scores calculated represent a continuum

of credit risk from subprime (highest risk) to super prime (lowest risk).

View GAO-19-430. For more information,

contact

Alicia Puente Cackley at (202) 512-

8678 or

Why GAO Did This Study

The Economic Growth, Regulatory

Relief, and Consumer Protection Act

enabled lenders to offer a rehabilitation

program to private student loan

borrowers who have a reported default

on their credit report. The lender may

remove the reported default from credit

reports if the borrower meets certain

conditions. Congress included a

provision in statute for GAO to review

the implementation and effects of

these programs.

This report examines (1) the factors

affecting financial institutions’

participation in private student loan

rehabilitation programs, (2) the risks

the programs may pose to financial

institutions, and (3) the effects the

programs may have on student loan

borrowers’ access to credit. GAO

reviewed applicable statutes and

agency guidance. GAO also asked a

credit scoring firm to simulate the effect

on borrowers’ credit scores of

removing student loan defaults. GAO

also interviewed representatives of

regulators, some of the largest private

student loan lenders, other credit

providers, credit bureaus, credit

scoring firms, and industry and

consumer advocacy organizations.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making two recommendations,

including that CFPB provide written

clarification to nonbank private student

loan lenders on their authority to offer

private student loan rehabilitation

programs. CFPB does not plan to take

action on this recommendation and

stated that it was premature to take

action on the second recommendation.

GAO maintains that both

recommendations are valid, as

discussed in this report.

Page i GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

Letter 1

Background 4

No Banks Are Offering Rehabilitation Programs, and Authority Is

Unclear for Other Lenders 11

Private Student Loan Rehabilitation Programs Would Likely Pose

Minimal Risks to Financial Institutions 17

Private Student Loan Rehabilitation Programs Would Likely Result

In Minimal Improvements in Borrowers’ Access to Credit 20

Conclusions 25

Recommendations for Executive Action 26

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 26

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 30

Appendix II Comments from the Consumer

Financial Protection Bureau 38

Appendix III Comments from the National

Credit Union Administration 41

Appendix IV GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 42

Table

Table 1: Results of VantageScore Solutions, LLC, Simulation of

the Effect on a VantageScore 3.0 Credit Score of Adding

a Student Loan Delinquency to and Removing a Student

Loan Default from Borrowers’ Credit Profiles 34

Figures

Figure 1: Student Loan Market, September 2018 5

Figure 2: Example of Credit Reporting for a Borrower in a Private

Student Loan Rehabilitation Program 8

Contents

Page ii GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

Figure 3: Example of Simulated Effects on a Borrower’s

VantageScore 3.0 Credit Score of Removing a Student

Loan Default 22

Abbreviations

the Act Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and

Consumer Protection Act

CFPB Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

CRA consumer reporting agency

FCRA Fair Credit Reporting Act

FDIC Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

Federal Reserve Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

FFIEC Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council

FICO Fair Isaac Corporation

NCUA National Credit Union Administration

nonbank nonbank financial institution

nonbank state nonprofit state-affiliated lender

lender

OCC Office of the Comptroller of the Currency

VantageScore VantageScore Solutions, LLC

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

May 24, 2019

Congressional Committees

As of September 2018, nearly $120 billion in private student loan

balances (that is, all student loans that are not guaranteed by the federal

government) was outstanding in the United States.

1

Private student loans

can supplement federal student loans and other financial aid and help pay

for tuition, fees, books, and living expenses.

2

However, unlike federal

student loans, private student loan lenders may not offer as many flexible

relief options during periods of financial hardship. Borrowers who default

on any type of student loan can face serious consequences, including

damaged credit ratings and difficulty obtaining affordable credit in the

future.

After the passage of legislation in 1992, the Department of Education

established a loan rehabilitation option for federal student loans in default

(generally those 270 days past due).

3

Under this option, borrowers have

the default removed from their credit reports after making nine on-time

monthly payments within 10 months. To facilitate private student loan

borrowers’ access to comparable programs, in 2018 Congress passed

the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act

(the Act), which amended the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) to allow

1

Throughout this report, we use the term “private student loans” to mean the same as

“private education loans.” A private education loan is defined as, among other

requirements, a loan provided by a private educational lender that “is issued expressly for

postsecondary educational expenses to a borrower….” 15 U.S.C. § 1650(a)(8)(A)(ii). This

estimate is from MeasureOne, a company that compiles data from 17 student loan lenders

and holders that represented about 62 percent of outstanding U.S. private student loan

balances as of September 30, 2018. MeasureOne, The MeasureOne Private Student

Loan Report (San Francisco, Calif.: Dec. 20, 2018).

2

Private student loans can be in-school, refinancing, or consolidation loans. In-school

loans are underwritten to fund a student’s academic year needs. Refinancing loans are

loans in which the lender pays off existing federal or private student loans and replaces

them with a new private student loan with a lower interest rate. Consolidation loans are

like refinancing loans and are used to pay off the balances on other loans. The Consumer

Financial Protection Bureau generally recommends that student loan borrowers exhaust

the availability of federal student loans before taking out private student loans because

federal student loans usually carry more flexible protections in the case of hardship and

offer fixed interest rates.

3

34 C.F.R. § 682.405; 20 U.S.C. § 1085(l); 34 C.F.R. §§ 682.200(b) and 685.102(b).

Letter

Page 2 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

financial institutions to offer rehabilitation programs.

4

The Act does not

require financial institutions to offer a rehabilitation program to their

private student loan borrowers, but financial institutions that are overseen

by one of the federal banking regulators must obtain approval of their

program’s terms and conditions from their regulator before offering a

program.

5

Rehabilitation programs provide student loan borrowers who

have previously defaulted on their loan an opportunity to demonstrate to

their lender a renewed willingness and ability to repay the loan by making

a certain number of consecutive, on-time monthly payments. After

completing these payments, borrowers may request that their financial

institutions remove the previously reported default on their student loans

from their credit reports.

6

Section 602 of the Act includes a provision for us to review the

implementation and effects of private student loan rehabilitation

programs. This report examines (1) the factors affecting financial

institutions’ participation in these programs, (2) the risks that these

programs may pose to financial institutions, and (3) the effects that these

programs may have on student loan borrowers’ access to future credit.

To accomplish these objectives, we reviewed the statements that the

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Federal Reserve),

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and the Office of the

Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) issued to their regulated entities

regarding private student loan rehabilitation programs. We reviewed the

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s (CFPB) and National Credit

4

Pub. L. No. 115-174, § 602, 132 Stat.1366 (2018), amends the Fair Credit Reporting Act,

§ 623(a)(1) (codified as 15 U.S.C. § 1681s-2(a)(1)). “Financial institution” is defined by

FCRA to include a state or national bank, state or federal savings and loan association, a

mutual savings bank, a state or federal credit union, or any other person that, directly or

indirectly, holds a transaction account belonging to a consumer. 15 U.S.C. § 1681a(t). In

this report we refer to private student loan rehabilitation programs, or rehabilitation

programs, to mean those explicitly described in the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief,

and Consumer Protection Act as well as similar programs that other private student loan

lenders may offer allowing borrowers who have defaulted on a student loan to request that

the default be removed from their credit report after making a certain number of

consecutive, on-time payments.

5

The federal banking regulators are the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Office of the Comptroller of

the Currency. 12 U.S.C. § 1813(z).

6

Borrowers may obtain benefits with respect to rehabilitating a loan under the Act only

once per loan.

Page 3 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

Union Administration’s (NCUA) legal authorities concerning rehabilitation

programs. We also asked VantageScore Solutions, LLC

(VantageScore)—a credit scoring firm—to conduct an analysis simulating

the effects of derogatory credit marks on student loan borrowers’

VantageScore 3.0 credit score.

In addition, we interviewed representatives from a nongeneralizable

sample of 15 private student loan lenders: five banks and two credit

unions with among the largest private student loan portfolios and eight

nonbank financial institutions (nonbank). The eight nonbanks included

three for-profit nonbank lenders and five nonprofit state-affiliated lenders

(nonbank state lenders).

7

We identified the for-profit nonbank lenders and

nonbank state lenders through discussions with federal agency officials

and a trade association for nonbank state lenders, as well as

documentary sources with data on nonbank private student loan lenders.

Because this sample is nongeneralizable, our results cannot be

generalized to all private student loan lenders.

We also interviewed representatives from a nongeneralizable sample of

seven credit providers (of mortgages, automobile loans, and credit cards)

about potential risks and effects of private student loan rehabilitation

programs.

8

We selected these credit providers based on their size and, to

the extent applicable, their federal regulator to include a mix of entities

overseen by different regulators. Because this sample is

nongeneralizable, our results cannot be generalized to all credit

providers. We interviewed officials from FDIC, the Federal Reserve,

NCUA, OCC, and CFPB about their implementation of the Act’s

provisions on private student loan rehabilitation programs and the

potential risks and effects for financial institutions and student loan

borrowers.

Finally, we interviewed officials from the Department of Education and the

Federal Trade Commission, which oversee the federal student loan

7

Nonbanks are broadly defined as institutions other than banks that offer financial

services. Loan or finance companies are common examples of nonbanks. Nonbank state

lenders provide private student loans to residents of their states and out-of-state students

attending in-state schools. These lenders are mission-driven entities focused on

increasing college access and affordability in their states, among other things, and are

funded through tax-advantaged bond funding.

8

For purposes of this report, we defined credit providers to include any bank or nonbank

entity that provides installment loans or revolving lines of credit to individual consumers.

Page 4 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

rehabilitation program and credit reporting industry, respectively. We also

interviewed representatives of four consumer reporting agencies (CRA);

the two credit scoring firms that develop credit score models with

nationwide coverage, Fair Isaac Corporation (FICO) and VantageScore;

banking, credit reporting, and student loan lending and servicing industry

groups; and consumer advocacy organizations. We determined that all of

the data and data sources we used in this report and the analyses

conducted by VantageScore were sufficiently reliable for reviewing the

implementation and effects of private student loan rehabilitation

programs. See appendix I for a more detailed discussion of our scope

and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2018 to May 2019 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Private student loans are not guaranteed by the federal government.

Generally, private lenders underwrite the loans based on the borrower’s

credit history and ability to repay, and they often require a cosigner.

Private student loans generally carry a market interest rate, which can be

a variable rate that is higher than that of federal student loans. As of

September 30, 2018, five banks held almost half of all private student

loan balances. Other private student loan lenders include credit unions

and nonbanks:

• Credit unions originate private student loans either directly or

indirectly through a third party.

• Nonbanks include both for-profit nonbank lenders and nonbank state

lenders. For-profit nonbank lenders can originate, service, refinance,

and purchase loans. Nonbank state lenders promote affordable

access to education by generally offering low, fixed-rate interest rates

and low or no origination fees on student loans.

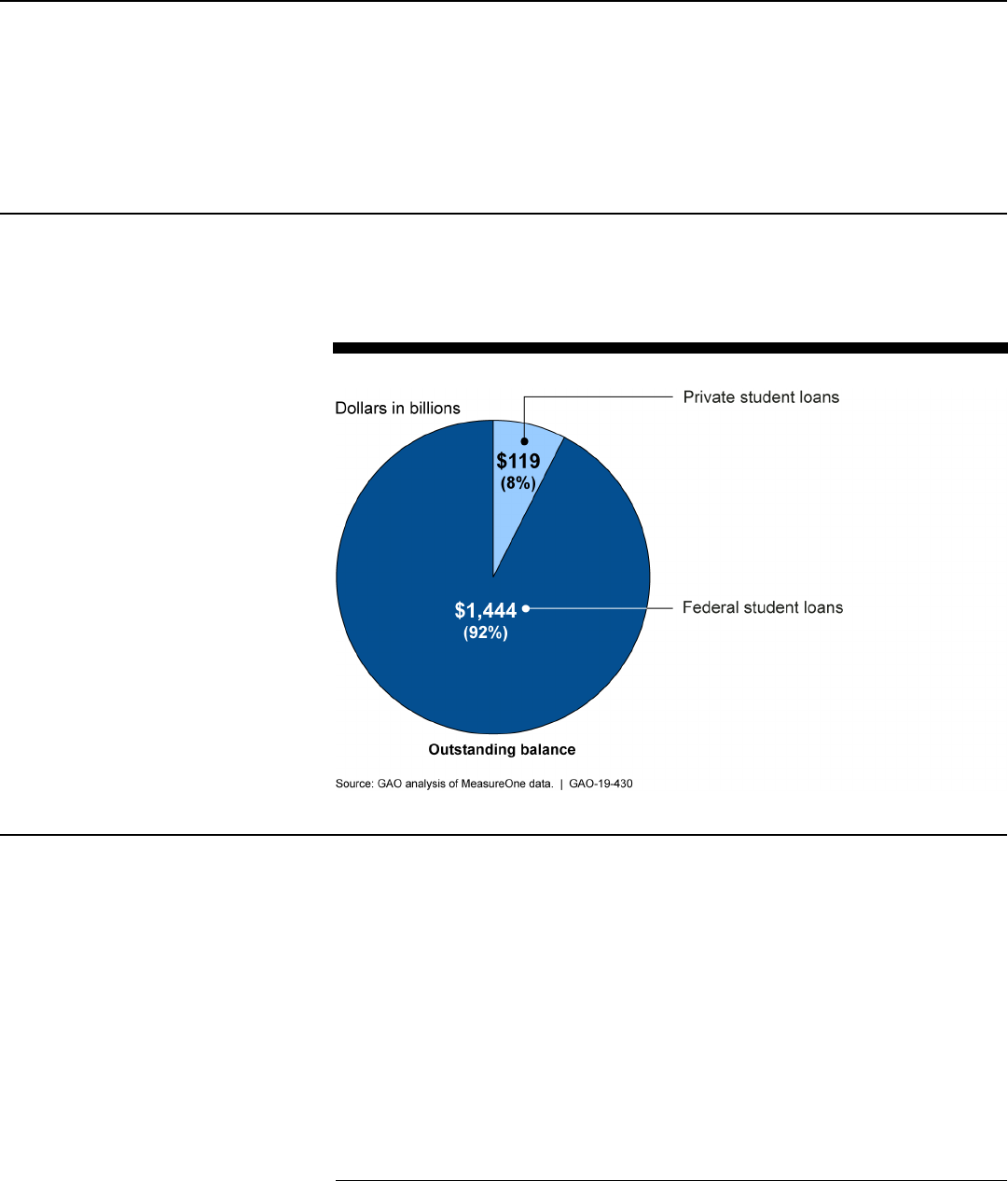

As of September 2018, outstanding private student loan balances made

up about 8 percent of the $1.56 trillion in total outstanding student loans

Background

Private Student Loan

Market

Page 5 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

(see fig. 1). The volume of new private student loans originated has

fluctuated, representing about 25 percent of all student loans originated in

academic year 2007–2008, 7 percent in 2010–2011 (after the financial

crisis), and 11 percent in 2017–2018.

9

Figure 1: Student Loan Market, September 2018

FCRA, the primary federal statute that governs consumer reporting, is

designed to promote the accuracy, fairness, and privacy of information in

the files of CRAs. FCRA, and its implementing regulation, Regulation V,

govern the compilation, maintenance, furnishing, use, and disclosure of

consumer report information for credit, insurance, employment, and other

eligibility decisions made about consumers. The consumer reporting

market includes the following entities:

• CRAs assemble or evaluate consumer credit information or other

consumer information for the purpose of producing consumer reports

(commonly known as credit reports). Equifax, Experian, and

TransUnion are the three nationwide CRAs.

9

Data for academic year 2017–2018 are preliminary. The College Board, Trends in

Student Aid 2018, (New York, N.Y.: October 2018).

Consumer Reporting for

Private Student Loans

Page 6 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

• Data furnishers report information about consumers’ financial

behavior, such as repayment histories, to CRAs. Data furnishers

include credit providers (such as private student loan lenders),

utilities, and debt collection agencies.

• Credit report users include banks, employers, and others that use

credit reports to make decisions on an individual’s eligibility for

products and services such as credit, employment, housing, and

insurance.

FCRA imposes duties on data furnishers with respect to the accuracy of

the data they furnish.

10

Data furnishers are required to, among other

things, refrain from providing CRAs with information they know or have

reasonable cause to believe is inaccurate and develop reasonable written

policies and procedures regarding the accuracy of the information they

furnish. The Act entitles financial institutions that choose to offer a private

student loan rehabilitation program that meets the Act’s requirements a

safe harbor from potential inaccurate information claims under FCRA

related to the removal of the private student loan default from a credit

report. To assist data furnishers in complying with their responsibilities

under FCRA, the credit reporting industry has adopted a standard

electronic data-reporting format called the Metro 2® Format. This format

includes standards on how and what information furnishers should report

to CRAs on private student loans.

11

The information that private student loan lenders furnish to CRAs on their

borrowers includes consumer identification; account number; date of last

payment; account status, such as in deferment, current, or delinquent

(including how many days past due); and, if appropriate, information

indicating defaults.

12

An account becomes delinquent on the day after the

10

Accuracy for the purposes of furnishers’ obligations means that the information a

furnisher provides to a CRA about an account or other relationship with the consumer

correctly: (1) reflects the terms of and liability for the account or other relationship, (2)

reflects the consumer’s performance and other conduct with respect to the account or

other relationship, and (3) identifies the appropriate consumer. 12 C.F.R. § 1022.41(a).

11

As of March 2019, revisions to the credit reporting standards and guidelines for private

student loans were planned, and the Consumer Data Industry Association hopes to

complete the revisions in 2019.

12

FCRA requires a person who furnishes information to a CRA regarding a delinquent

account being placed for collection, charged to profit or loss, or subjected to any similar

action to notify the CRA of the date of delinquency on the account not later than 90 days

after furnishing the information. Some private student loan lenders use third-party

servicers to service their student loan portfolio and provide credit reporting information to

CRAs on their behalf.

Page 7 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

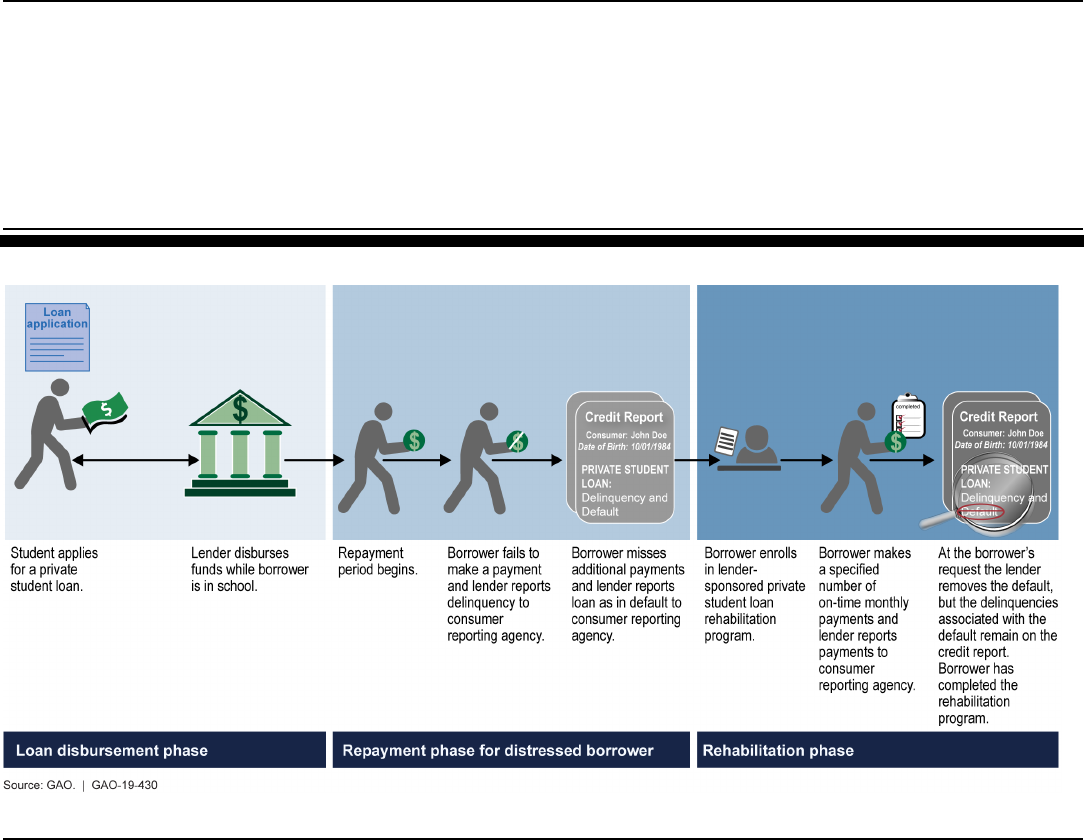

due date of a payment when the borrower fails to make a full payment.

Private student loan lenders’ policies and terms of loan contracts

generally determine when a private student loan is in default. While

private student loan lenders may differ in their definitions of what

constitutes a default, federal banking regulator policy states that closed-

end retail loans (which include private student loans) that become past

due 120 cumulative days from the contractual due date should be

classified as a loss and “charged off.”

13

Private student loan lenders can

indicate that a loan is in default and they do not anticipate being able to

recover losses on it by reporting to CRAs one of a number of Metro 2®

Format status codes. Participation in a private student loan rehabilitation

program entitles borrowers who successfully complete the program to

request that the indicator of a student loan default be removed from their

credit report, but the delinquencies leading up to the default would remain

on the credit report.

14

Figure 2 shows an example of credit reporting for a

borrower who defaults on a private student loan and completes a

rehabilitation program.

13

See Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, Uniform Retail Credit

Classification and Account Management Policy, 64 Fed. Reg. 6655 (Feb. 10, 1999).

Although NCUA did not adopt the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council’s

(FFIEC) policy and issued its own loan charge-off guidance, it does refer federally insured

credit unions to the FFIEC policy for best practices in developing their charge-off policies.

Although the FFIEC policy does not define “default,” throughout this report, we use the

term to describe private student loans that have been charged off by banks and credit

unions.

14

When we refer to the successful completion of a private student loan rehabilitation

program in this report, we are referring to borrowers who make the lender-specified

number of consecutive, on-time monthly payments, request that the lender remove a

reported default and have the private student loan default indicator removed from their

credit report.

Page 8 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

Figure 2: Example of Credit Reporting for a Borrower in a Private Student Loan Rehabilitation Program

A credit score is a measure that credit providers use to predict financial

behaviors and is typically computed using information from consumer

credit reports. Credit scores can help predict the likelihood that a

borrower may default on a loan, file an insurance claim, overdraw a bank

account, or not pay a utility bill. FICO and VantageScore are the two firms

that develop credit score models with nationwide coverage. FICO

develops credit score models for distribution by each of the three

nationwide CRAs, whereas VantageScore’s models are developed across

the three CRAs resulting in a single consistent algorithm to assess risk.

FICO and VantageScore each have their own proprietary statistical credit

score models that choose which consumer information to include in

calculations and how to weigh that information. The three nationwide

CRAs also develop credit score models derived from their own data.

There are different types of credit scores, including generic, industry-

specific, and custom. Generic scores are based on a representative

sample of all individuals in a CRA’s records, and the information used to

predict repayment is limited to the information in consumer credit records.

Generic scores are designed to predict the likelihood of a borrower not

Credit Scoring

Page 9 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

paying as agreed in the future on any type of credit obligation. Both FICO

and VantageScore develop generic credit scores. FICO and

VantageScore generic scores generally use a range from 300 to 850, with

higher numbers representing lower credit risk. For example,

VantageScore classifies borrowers in the following categories: subprime

(those with a VantageScore of 300–600), near prime (601–660), prime

(661–780), and super prime (781–850). A prime borrower is someone

who is considered a low-risk borrower and likely to make loan payments

on time and repay the loan in full, whereas a subprime borrower has a

tarnished or limited credit history. FICO and VantageScore generic scores

generally use similar elements in determining a borrower’s credit score,

including a borrower’s payment history, the amounts owed on credit

accounts, the length of credit history and types of credit, and the number

of recently opened credit accounts and credit inquiries.

FICO has developed industry-specific scores for the mortgage,

automobile finance, and credit card industries. These scores are

designed to predict the likelihood of not paying as agreed in the future on

these specific types of credit. In addition, credit providers sometimes use

custom credit scores instead of, or in addition to, generic credit scores.

Credit providers derive custom scores from credit reports and other

information, such as account history, from the lender’s own portfolio. The

scores can be developed internally by credit providers or with the

assistance of external parties such as FICO or the three nationwide

CRAs.

CFPB has supervisory authority over certain private student loan lenders,

including banks and credit unions with over $10 billion in assets and all

nonbanks, for compliance with Federal consumer financial laws.

15

CFPB

also has supervisory authority over the largest CRAs and many of the

entities that furnish information about consumers’ financial behavior to

CRAs.

16

To assess compliance with Federal consumer financial laws,

15

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act defines Federal

consumer financial laws to include the Consumer Financial Protection Act of 2010 (Title X

of the Dodd-Frank Act) itself and a number of other consumer laws and the implementing

regulations. 12 U.S.C. § 5481(14). For example, Federal consumer financial laws include

the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, the Truth in Lending Act, the Fair Debt Collection

Practices Act, and FCRA.

16

CFPB also has supervisory authority over many of the entities that use the information

for credit decisions.

Federal Oversight of

Private Student Loans

Page 10 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

CFPB conducts compliance examinations. According to CFPB, because

of its mission and statutory requirement regarding nonbank supervision, it

prioritizes its examinations by focusing on risks to consumers rather than

risks to institutions. Given the large number, size, and complexity of the

entities under its authority, CFPB prioritizes its examinations by focusing

on individual product lines rather than all of an institution’s products and

services. CFPB also has enforcement authority under FCRA regarding

certain banks, credit unions, and nonbanks and broad authority to

promulgate rules to carry out the purposes of FCRA.

17

The prudential regulators—FDIC, Federal Reserve, NCUA, and OCC—

oversee all banks and most credit unions that offer private student loans.

Their oversight includes routine safety and soundness examinations for

all regulated entities. These examinations may include a review of

operations, including policies, procedures, and practices, to ensure that

private student loans are not posing a risk to the entities’ safety and

soundness. Prudential regulators also have supervisory authority for

FCRA compliance for banks and certain credit unions with $10 billion or

less in assets.

17

CFPB does not have rulemaking authority for FCRA Section 615(e), regarding red flag

guidance and regulations, and Section 628, regarding disposal of records (codified as 15

U.S.C. § 1681m(e) and 15 U.S.C. § 1681w, respectively).

Page 11 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

As of January 2019, none of the five banks with the largest private

student loan portfolios that we contacted offered rehabilitation programs

for defaulted private student loans. In addition, officials from the federal

banking regulators told us that as of March 2019, no banks had submitted

applications to have rehabilitation programs approved. Representatives

from three of the five banks we contacted told us they had decided not to

offer a rehabilitation program, and the other two had not yet made a final

determination.

Representatives from these five banks provided several reasons they

were not offering rehabilitation programs for private student loans.

• Low delinquency and default rates. All five banks’ representatives

stated that they had low default rates for private student loans, so the

demand for these programs would be low for each bank.

• Availability of predefault payment programs. Representatives of all

five banks said they already offer alternative payment programs, such

as forbearance, to help prevent defaults, and two of them explicitly

noted this as a reason that a rehabilitation program was unnecessary.

• Operational uncertainties. Most of the banks’ representatives were

not sure how they would operationalize rehabilitation programs. One

bank’s representatives said that they sell defaulted loans to debt

purchasers and that it would be difficult to offer rehabilitation

programs for loans that had been sold. Representatives of two other

banks said that the banks’ systems are not able to change the status

of a loan once it has defaulted, so they were not certain how their

systems would track rehabilitated loans. Another bank’s

representatives said that they did not know how rehabilitated loans

would be included for accounting purposes in developing their

financial statements.

No Banks Are

Offering

Rehabilitation

Programs, and

Authority Is Unclear

for Other Lenders

Banks and Credit Unions

Are Not Offering

Rehabilitation Programs,

but Federal Banking

Regulators Have

Established Approval

Processes

Page 12 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

• Reduced borrower incentives to avoid default. Representatives

from two banks said they believed the option to rehabilitate a

defaulted loan might reduce borrowers’ incentives to avoid default or

to enter a repayment program before default.

• Risk of compliance violations. One bank representative said a

rehabilitation program could put the bank at risk for violations of unfair

and deceptive acts and practices if borrowers misunderstood or

misinterpreted how much the program would improve their credit

scores. Representatives from this bank and another explained that

they did not know how much the program would improve credit

scores, limiting their ability to describe the program’s benefit to

borrowers.

Representatives from three of these banks and other organizations,

however, noted that there could be advantages for banks to offer private

student loan rehabilitation programs. Representatives from the banks said

these programs could help banks recover some nonperforming debt, and

one of these representatives stated the program could be marketed to

borrowers as a benefit offered by the bank. A representative of a

consumer advocacy group said a rehabilitation program could improve a

bank’s reputation by distinguishing the bank from peer institutions that do

not offer rehabilitation for private student loans.

Because NCUA is not one of the federal banking regulators by statutory

definition, officials said the Act does not require credit unions to seek

approval from the agency before offering a rehabilitation program. NCUA

officials told us examiners would likely review private student loan

rehabilitation programs for the credit unions that choose to offer them as

part of normal safety and soundness examinations. The two credit unions

we spoke with—which are among the largest credit union providers of

private student loans—told us they do not plan to offer rehabilitation

programs. One of these credit unions cited reasons similar to those

offered by banks, including a low private student loan default rate that

suggested there would be a lack of demand for a rehabilitation program.

The other credit union explained that it was worried about the effect of

removing defaults from credit reports on its ability to make sound lending

decisions. NCUA officials also noted that as of January 2019, they had

not received any inquiries from credit unions about these programs.

OCC, FDIC, and the Federal Reserve have issued information regarding

the availability of private student loan rehabilitation programs to their

regulated entities, including how they would review applications. In doing

so, the agencies informally coordinated to ensure that the statements

Page 13 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

issued would contain similar information on rehabilitation programs. The

three agencies’ statements explained that their regulated entities must

receive written approval to begin a program and that the relevant agency

would provide feedback or notify them of its decision within 120 days of

receiving a written application.

18

The agencies will review the proposed

program to ensure that it requires borrowers to make a minimum number

of consecutive, on-time, monthly payments that demonstrate renewed

ability and willingness to repay the loan.

19

Uncertainty exists regarding two issues with private student loan

rehabilitation programs. First, some nonbank private student loan lenders

are not certain that they have the authority to implement these programs.

Second, the Act does not explain what constitutes a “default” for the

purposes of removing information from credit reports.

With regard to nonbank state lenders, uncertainty exists about their

authority under FCRA to offer private student loan rehabilitation programs

that include removing information from credit reports. As discussed

previously, for financial institutions such as banks and credit unions, the

Act provides an explicit safe harbor to request removal of a private

student loan default from a borrower’s credit report and remain in

compliance with FCRA. However, the Act does not specify that for-profit

nonbank lenders and nonbank state lenders have this same authority.

Representatives of the five nonbank state lenders we spoke with had

different interpretations of their authority to offer rehabilitation programs.

At least two nonbank state lenders currently offer rehabilitation programs,

and their representatives told us they believed they have the authority to

do so. Another nonbank state lender told us its state has legislation

18

See Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Statement on Programs for Rehabilitation

of Private Education Loans (Section 602 Rehabilitation Programs), OCC Bulletin 2018-48

(Washington, D.C.: Dec. 27, 2018); Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Voluntary

Private Education Loan Rehabilitation Programs, FDIC Financial Institution Letter FIL-5-

2019 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 4, 2019); and Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

System, Voluntary Private Education Loan Rehabilitation Programs, Federal Reserve

Supervision and Regulation Letter SR19-2 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 4, 2019).

19

OCC issued its statement separately from FDIC and the Federal Reserve since it was

concurrently updating examiner guidance and training materials. See Office of the

Comptroller of the Currency, Comptroller’s Handbook: Student Lending, Version 1.3

(Washington, D.C.: Dec. 27, 2018).

Uncertainty Exists about

Nonbank Lenders’

Authority and What

Information Should Be

Removed from a Credit

Report

Uncertainty about Nonbank

State Lenders’ Authorities

Page 14 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

pending to implement such a program. In contrast, representatives of two

other nonbank state lenders told us they were interested in offering a

rehabilitation program but did not think that they had the authority to do

so. In addition, representatives from a trade association that represents

nonbank state lenders noted that confusion exists among some of their

members and they are seeking a way to obtain explicit authority for

nonbank lenders to offer rehabilitation programs for their private student

loans. Two trade associations that represent nonbank state lenders also

told us that some of their members would be interested in offering these

programs if it was made explicit that they were allowed to do so.

CFPB officials told us the agency has not made any determination on

whether it plans to clarify for nonbanks—including for-profit nonbank

lenders and nonbank state lenders—if they have the authority under

FCRA to have private student loan defaults removed from credit reports

for borrowers who have completed a rehabilitation program. CFPB

officials said that the agency does not approve or prevent its regulated

entities from offering any type of program or product. Unlike for the

federal banking regulators, the Act did not require CFPB to approve

rehabilitation programs offered by the entities it regulates. However,

CFPB does have general FCRA rulemaking authority. It generally also

has FCRA enforcement and supervisory responsibilities over its regulated

entities, which includes certain entities that originate private student

loans. This authority allows the agency to provide written clarification of

provisions or define terms as needed. As a result, CFPB could play a role

in clarifying for nonbanks whether they are authorized under FCRA to

offer private student loan rehabilitation programs.

Federal internal control standards state that management should

externally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the

entity’s objectives.

20

Without clarification from CFPB on nonbanks’

authority to offer private student loan rehabilitation programs that allow

them to delete information from the borrower’s credit report, there will

continue to be a lack of clarity on this issue among these entities.

Providing such clarity could—depending on CFPB’s interpretation—result

in additional lenders offering rehabilitation programs that would allow

more borrowers the opportunity to participate, or it could help ensure that

20

GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO-14-704G

(Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014).

Page 15 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

only those entities CFPB has interpreted as being eligible to offer

programs are doing so.

Statutory changes made to FCRA by the Act do not explain what

information on a consumer’s credit report constitutes a private student

loan “default” that may be removed when a borrower successfully

completes a rehabilitation program. According to the three nationwide

CRAs and a credit reporting trade association, the term “default” is not

used in credit reporting for private student loans. As discussed previously,

private student loan lenders use one of a number of Metro 2® Format

status codes to indicate that a loan is in default (i.e., they do not

anticipate being able to recover losses on the loan). Representatives of

the CRAs and a credit reporting trade association said that private

student loan lenders will need to make their own interpretation of what

information constitutes a default for the purposes of removing information

from a credit report following successful completion of a private student

loan rehabilitation program.

The statements issued by FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and OCC on

rehabilitation programs do not explain what information constitutes a

private student loan “default” that may be removed from borrowers’ credit

reports upon successful completion of a rehabilitation program. Officials

from FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and OCC explained that they do not

have the authority to interpret what constitutes a private student loan

default on credit reports because the responsibilities for interpreting

FCRA fall under CFPB. CFPB officials told us they are monitoring the

issue but have not yet determined if there is a need to address it.

21

21

In 2010, we reported similar concerns when the Department of the Treasury

implemented its mortgage loan modification program in 2009. In particular, we noted

inconsistencies in servicers’ criteria for determining imminent default. We recommended

that the Department of the Treasury establish clear and specific criteria for determining

whether a borrower is in imminent default to ensure greater consistency across servicers.

At the time the report issued, the agency indicated that it did not plan to establish specific

criteria for servicers to follow in determining whether a borrower was in imminent danger

of default because it felt that servicers and investors were in the best position to make this

determination. The Department of the Treasury stopped taking new requests for

assistance or applications for any of its mortgage loan modification programs as of

December 30, 2016. We have closed this recommendation as not implemented. GAO,

Troubled Asset Relief Program: Further Actions Needed to Fully and Equitably Implement

Foreclosure Mitigation Programs, GAO-10-634 (Washington, D.C.: June 24, 2010).

No Standard for What

Constitutes a “Default”

Page 16 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

Given CFPB’s rulemaking authority for FCRA, it could clarify the term

“default” for private student loan lenders. In doing so, CFPB could obtain

insight from the prudential regulators and relevant industry groups on how

private student loan lenders currently report private student loan defaults

on credit reports and on how to develop a consistent standard for what

information may be removed. According to federal internal control

standards, management should externally communicate the necessary

quality information to achieve objectives.

22

This can include obtaining

quality information from external parties, such as other regulators and

relevant industry groups. Without clarification from CFPB, there may be

differences among private student loan lenders in what information they

determine constitutes a “default” and may be removed from a credit

report. Variations in lenders’ interpretations could have different effects on

borrowers’ credit scores and credit records, resulting in different treatment

of borrowers by credit providers. This could affect borrowers’ access to

credit or the terms of credit offered, such as interest rates or the size of

down payments required on a variety of consumer loans. In addition, as

mentioned previously, the credit reporting industry follows a standard

reporting format to help ensure the most accurate credit reporting

information possible. Without clarification on what information may be

removed from credit reports following successful completion of

rehabilitation programs, differences in lenders’ interpretation could

introduce inconsistencies in credit reporting data that may affect their

accuracy.

22

GAO-14-704G.

Page 17 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

Rehabilitation programs for private student loans are expected to pose

minimal additional risk to banks’ and credit unions’ safety and soundness.

Prudential regulators require that banks and credit unions underwrite

student loans to mitigate risks and ensure sound lending practices, and

OCC guidance specifies that underwriting practices should minimize the

occurrence of defaults and the need for repayment assistance. Lenders

generally use underwriting criteria based on borrowers’ credit information

to recognize and account for risks associated with private student loans.

According to officials from OCC, FDIC, and the Federal Reserve and

representatives from the major bank and credit union private student loan

lenders we spoke with, lenders participating in private student loan

rehabilitation programs would face minimal additional risks for several

reasons:

• Loans are already classified as a loss. Loans entering a

rehabilitation program are likely to be 120 days past due and to have

been charged off, and thus they would have already been classified

as a loss by banks and credit unions. OCC officials told us a program

to rehabilitate these loans would, therefore, pose no additional risks to

the safety and soundness of institutions that offer them.

• Default rates are low, and loans typically use cosigners.

Representatives from the five major banks and two credit unions told

us that private student loans generally perform well and have low

rates of delinquencies and defaults. Aggregate data on the majority of

outstanding loan balances show that the default rate for private

student loans was below 3 percent from the second quarter of 2014

Private Student Loan

Rehabilitation

Programs Would

Likely Pose Minimal

Risks to Financial

Institutions

Programs Are Expected to

Pose Little Safety and

Soundness Risk for Banks

and Credit Unions

Page 18 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

through the third quarter of 2018.

23

Lenders also generally require

borrowers of private student loans to have cosigners—someone who

is liable to make payments on the loan should the student borrower

default—which helps reduce the risk of the loan not being repaid.

Since the academic year 2010–2011, the rate of undergraduate

private student loan borrowers with cosigners has exceeded 90

percent.

24

• Private student loan portfolios are generally small. Private student

loans make up a small portion of the overall loan portfolios for most of

the banks and credit unions we spoke with. For four of the five major

banks with the largest portfolios of private student loans, these

constituted between about 2 percent to 11 percent of their total loan

portfolio in 2017. The fifth bank’s entire portfolio was education

financing, with private student loans accounting for about 93 percent

of its 2017 portfolio. For the two credit unions we contacted, private

student loans constituted about 2 percent and 6 percent of their total

assets in 2018.

Private student loan rehabilitation programs may create certain

operational costs for banks or credit unions that offer them. However, no

representatives of the five banks and two credit unions with whom we

spoke were able to provide a cost estimate since none had yet designed

or implemented such a program. Representatives from four banks and

one credit union we spoke with said that potential costs to implement a

rehabilitation program would be associated with information technology

systems, designing and developing new systems to manage the program,

increased human resource needs, additional communications with

borrowers, credit reporting, compliance, monitoring, risk management,

and any related legal fees. In addition, like any other type of consumer

loan, banks and credit unions could face potential risks with private

student loan rehabilitation programs, including operational, compliance, or

23

The default rate data presented here represent annualized charge-off rates.

MeasureOne defines the annualized charge-off rate as the amount of gross charge-offs

for a quarter divided by the quarter-end balance in repayment loan status, multiplied by

four (or annualized). MeasureOne, The MeasureOne Private Student Loan Report (Dec.

20, 2018). We compared private student loan default rates to the default rates of other

types of consumer loans, including automobile loans, credit cards, and mortgages, and

found that the estimated private student loan default rate is comparable to the default

rates of these other types of consumer loans.

24

MeasureOne, The MeasureOne Private Student Loan Report (Dec. 20, 2018).

Page 19 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

reputational risks.

25

For example, a representative of one bank cited

operational risks such as those that could stem from errors in credit

reporting or inadequate collection practices for rehabilitated private

student loans.

One concern about removing information from credit reports—as

authorized in connection with the Act’s loan rehabilitation programs—is

that it could degrade the quality of the credit information that credit

providers use to assess the creditworthiness of potential borrowers.

However, the removal of defaults from credit reports resulting from loan

rehabilitation programs is unlikely to affect financial institutions’ ability to

make sound lending decisions, according to prudential regulator officials

and representatives from three private student lenders and three other

credit providers with whom we spoke. OCC and FDIC officials and

representatives from two of these private student lenders noted that

because rehabilitation programs leave the delinquencies leading up to the

default on borrowers’ credit reports, lenders would still be able to

adequately assess borrower risk. In addition, representatives from one

automobile lender and one mortgage lender said that over time, the

methods they use to assess creditworthiness would be able to detect

whether rehabilitated private student loans were affecting their ability to

identify risk patterns in credit information and they could adjust the

methods accordingly.

Representatives from the Federal Reserve provided three additional

reasons why they expected that rehabilitation programs would have little

effect on banks’ and credit unions’ lending decisions. First, under the

statutory requirement for private student loan rehabilitation, removal of a

default from a borrower’s credit report can only occur once per loan. A

single default removal would be unlikely to distort the accuracy of credit

reporting in general. Second, they said that borrowers who have

successfully completed a rehabilitation program by making consecutive

on-time payments have demonstrated a proven repayment record, and

therefore they likely represent a better credit risk. Finally, because

participation in the private student loan rehabilitation program is expected

25

Operational risk arises from inadequate or failed internal processes or systems, human

errors or misconduct, or adverse external events. Compliance risk arises from violations of

laws or regulations, or from nonconformance with prescribed practices, internal bank

policies and procedures, or ethical standards. Reputational risk arises from negative

public opinion.

Rehabilitation Programs

Are Expected to Have

Little Effect on Financial

Institutions’ Ability to Make

Prudent Lending

Decisions

Page 20 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

to be low, its effect on the soundness of financial institutions’ lending

decisions is expected to be minimal.

The effects of private student loan rehabilitation programs on most

borrowers’ access to credit would likely be minimal. A simulation

conducted by VantageScore found that removing a student loan default

increased a borrower’s credit score by 8 points, on average.

26

An 8 point

rise in a borrower’s credit score within VantageScore’s range of 300 to

850 represents only a very small improvement to that borrower’s

creditworthiness. Therefore, most borrowers who successfully completed

a private student loan rehabilitation program would likely see minimal

improvement in their access to credit, particularly for credit where the

decision-making is based solely on generic credit scores.

26

In this section, we refer to the removal of student loan defaults generally, rather than

private student loan defaults in particular, because it is not always possible to differentiate

between federal and private student loans in credit reporting information, according to

credit scoring firms with whom we spoke. The 95 percent confidence interval for this

estimate is (7.57, 7.79) with a point estimate of 7.68. The estimate includes all borrowers

with at least one student loan balance greater than $0 and who also had at least one

student loan delinquency or default in 2016–2018. Analysis of borrowers with the same

characteristics in 2014–2016 and in 2015–2017 produced similar results. For purposes of

this analysis, a default is defined as a loan that is 90 or more days past due (including

charge-offs), and a delinquency is defined as a loan that is 30 or 60 days past due. The

simulated borrower outcomes are meant to be illustrative. The results of the

VantageScore analysis only apply to VantageScore 3.0 credit scores in 2016–2018 and

may not be generalizable to effects on other VantageScore credit scores or FICO credit

scores, or for different years. Additionally, because this is a simulation, it is unlikely that

any one borrower’s credit profile exactly matches the average profiles used in the

simulations. See appendix I for additional information on this analysis.

Private Student Loan

Rehabilitation

Programs Would

Likely Result In

Minimal

Improvements in

Borrowers’ Access to

Credit

Effect of Rehabilitation

Programs on Most

Borrowers’ Access to

Credit Would Likely Be

Small

Page 21 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

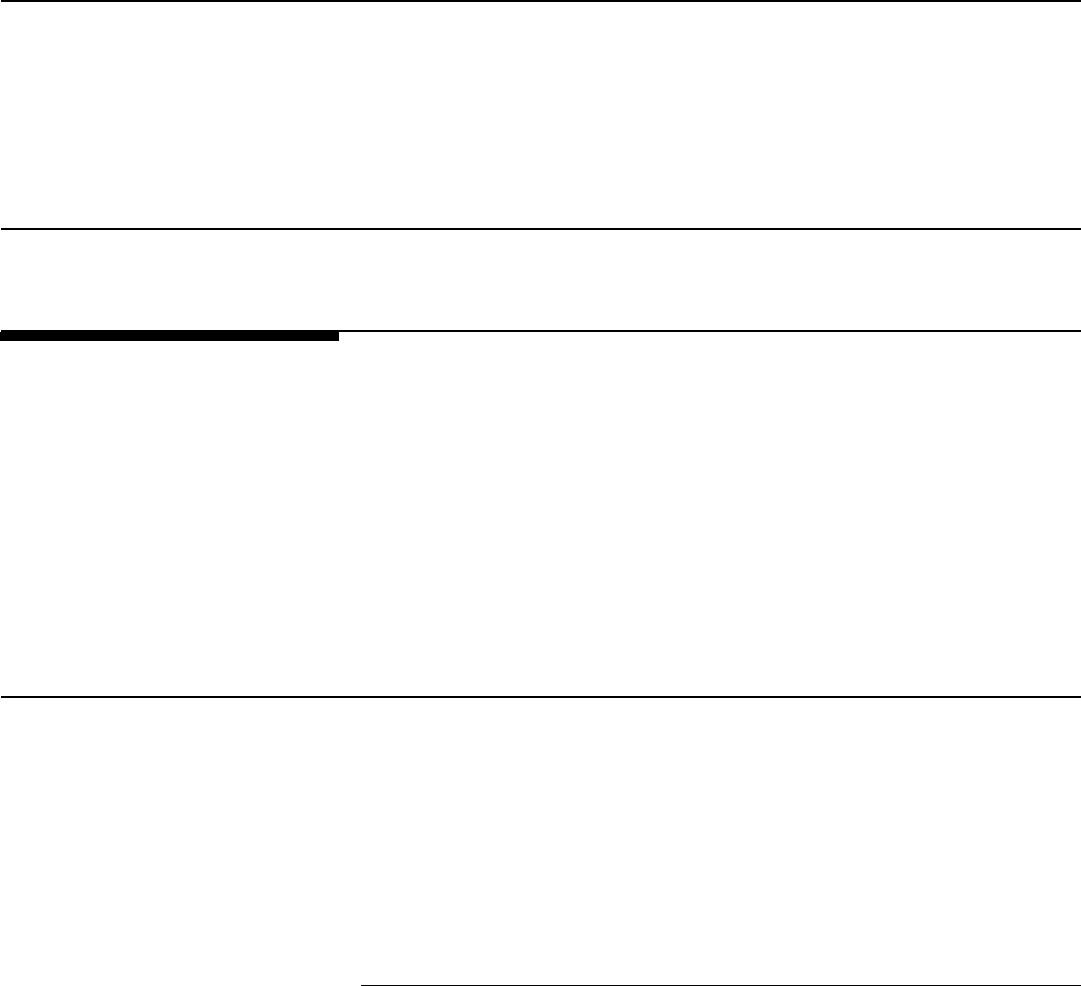

The effect of a rehabilitation program on credit scores will likely be

somewhat greater for borrowers with lower credit scores, and smaller for

borrowers with higher credit scores. For example, the VantageScore

simulation suggests that borrowers in the subprime range (with scores of

300–600) could see score increases of 11 points, on average, while

borrowers in the prime (661–780) and super prime (781–850) ranges

could see increases of less than 1 point, on average (see fig. 3).

27

The

effect of removing a default from a credit report varies among borrowers

because a credit score is influenced by other information in a borrower’s

credit report, such as other outstanding derogatory credit markers, the

length of time since the default, and other types of outstanding loans.

27

The 95 percent confidence intervals for these estimates are (10.51, 10.83) and (0.85,

1.04) with point estimates of 10.67 and 0.94, respectively.

Factors Credit Providers Consider Prior to

Lending

Credit providers assess a borrower’s

creditworthiness based on several factors,

including the following:

• Generic credit scores: Credit providers

can rely solely on generic credit scores,

such as those developed by Fair Isaac

Corporation and VantageScore Solutions,

LLC, to make lending decisions. Credit

providers generally do not provide credit

to borrowers whose scores do not meet a

minimum threshold.

• Industry-specific credit scores: Certain

types of credit providers, such as

mortgage lenders, automobile loan

lenders, and credit card issuers, may use

industry-specific credit scores rather than

generic credit scores to make lending

decisions. This is because these scores

may help them better predict lending risks

specific to their industry.

• Internal credit reviews: Credit providers

can customize methods unique to their

institution that review different aspects of

borrowers’ credit information, such as

debt-to-income ratios, employment

history, and borrowers’ existing

relationships with the institution. Credit

providers may also develop custom credit

scores that are tailored to their specific

needs and include factors they have

deemed important in predicting risks of

nonpayment. Credit providers incorporate

their own internal data in these scores as

well as information contained in

borrowers’ credit reports.

Source: GAO, based on credit provider interviews. |

GAO-19-430

Page 22 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

Figure 3: Example of Simulated Effects on a Borrower’s VantageScore 3.0 Credit

Score of Removing a Student Loan Default

Note: A VantageScore 3.0 credit score models a borrower’s credit risk based on elements such as

payment history and amounts owed on credit accounts. The scores calculated represent a continuum

of credit risk from subprime (highest risk) to super prime (lowest risk).

Reasons that removing a student loan default may improve a borrower’s

credit score and access to credit only minimally include the following:

• Delinquencies remain in the credit report. A key reason that

removing a student loan default has a small effect on a credit score,

according to VantageScore officials, is that the delinquencies leading

to that default remain in the credit report for borrowers who

successfully complete rehabilitation programs. Adding a delinquency

Page 23 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

in the simulation decreased a credit score by 61 points, on average.

28

Thus, the simulation suggests that the increase in a credit score from

removing a student loan default is not as substantial as the decrease

from adding the initial delinquency.

• Credit scoring treats student loans differently. Some credit score

models place less emphasis on student loans than on other types of

consumer loans in predicting the risk of nonpayment. One credit

scoring firm and two CRAs we spoke with said that student loans

have a lower weight than other types of consumer loans in their

generic credit scoring algorithms. They explained that there are fewer

student loans than other types of consumer loans in the sample they

use to develop the score, and student debt has proved to be less

important statistically at predicting credit risk in their models. Student

loans also may have less weight in predicting defaults in industry-

specific or custom models of scores. A representative of one credit

scoring firm said the algorithm for an industry-specific credit score that

predicts the risk of nonpayment on a credit card may place less

emphasis on a student loan than the algorithm for a generic credit

score that is meant to predict risk more broadly. Further, CRA officials

we spoke with said that because their custom credit scoring models

are specific to clients’ needs, the models may not include student

loans as a predictor of default at all, or they may place greater

emphasis on student loans, depending on the clients’ needs.

• Borrowers in default typically already have poor credit. Borrowers

who complete a rehabilitation program have a high likelihood of

having other derogatory credit items in their credit report, in addition to

the student loan delinquencies that led to the default, according to a

study conducted by a research organization, several CRAs, and one

credit provider with whom we spoke.

29

The VantageScore simulation

also showed that borrowers who had at least one student loan

delinquency or default in their credit profile had an average of five

derogatory credit items in their profile. Because student loan defaults

and student loan delinquencies are both negative credit events that

28

The 95 percent confidence interval for this estimate is (-60.81, -60.57) with a point

estimate of -60.69. The estimate includes all borrowers with at least one student loan

balance greater than $0 in 2016–2018. In the VantageScore analysis that added a student

loan delinquency to borrowers’ credit profiles, borrowers had an average of 1.5

delinquencies or defaults previously existing in their credit profiles. For purposes of this

analysis, a delinquency is defined as a loan that is 30 or 60 days past due.

29

Urban Institute, Underwater on Student Loan Debt: Understanding Consumer Credit and

Student Loan Default (Washington, D.C.: August 2018).

Page 24 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

affect credit providers’ credit assessment methods, the removal of one

student loan default from a borrower’s credit report likely will not make

a large difference in how credit providers evaluate the borrower.

Consumer advocates and academic studies cited potential benefits of

rehabilitation programs apart from their effect on credit scores and access

to credit:

• Borrowers defaulting on private student loans issued by nonbank

state lenders could have wage garnishments stopped after

successfully completing a rehabilitation program.

• Rehabilitation would stop debt collection efforts against a private

student loan borrower.

• Participating in a loan modification program for one loan may help

borrowers better meet their other loan obligations, according to

studies we reviewed.

30

For example, one study found that

participation in mortgage modification programs was associated with

lower delinquency rates on nonmortgage loans.

31

However, programs may also have some disadvantages or pose

challenges to borrowers, according to representatives from consumer

advocacy groups and academic sources:

• A rehabilitation program may restart the statute of limitations on loan

collections, according to representatives of consumer advocacy

groups. Borrowers who redefault following entry into a rehabilitation

program near the end of the statute of limitations on their debt could

have collection efforts extended on these loans.

32

30

Paul S. Calem, Julapa Jagtiani, and William W. Lang, “Foreclosure Delay and Consumer

Credit Performance,” Journal of Financial Services Research, vol. 52 (2017): pp. 225–251;

Lei Ding, “Borrower Credit Access and Credit Performance after Loan Modifications,”

Empirical Economics, vol. 52 (2017): pp. 977–1005.

31

Ding, “Borrower Credit Access,” pp. 977–1005. Private student loan rehabilitation

programs may not be designed like the mortgage modification programs analyzed in this

study, and thus may not have the same effects.

32

According to OCC examiner guidance, a lawsuit is the main tool available to banks to

pursue collection of private student loans in default. Depending on the state, a bank may

need to consider the applicable statute of limitations to enforce private student loan court

judgments. Some states allow banks to continuously renew the judgments to avoid being

subjected to the statute of limitations. The statute runs until the time period has elapsed or

an action is taken that “tolls” the statute (stops it from running), such as filing a lawsuit in

court.

Programs May Hold

Additional Benefits as Well

as Disadvantages for

Borrowers

Page 25 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

• Programs may extend adverse credit reporting. Generally, negative

credit information stays on consumer reports for 7 or 10 years;

therefore, depending on when a borrower enters into a rehabilitation

program, a payment on the loan might prolong the adverse credit

reporting for that account.

• The lack of income-driven repayment programs offered to borrowers

in the private student loan market means that borrowers who

complete rehabilitation programs may have a high likelihood of

redefaulting on their loans.

33

• Because removing adverse information from credit reports does not

change a borrower’s underlying creditworthiness, improved credit

scores and access to credit may cause borrowers to borrow too much

relative to their ability and willingness to pay.

34

For example, one

study found that for consumers who had filed for bankruptcy, their

FICO scores and credit lines increased within the first year after the

bankruptcy was removed from their credit report.

35

However, the

study found the initial credit score increase had disappeared by about

18 months after the bankruptcy was removed and that debt and

delinquency were higher than expected, increasing the probability of a

future default.

Private student loan rehabilitation programs can provide an opportunity

for private student loan borrowers to help repair their credit reports.

However, some nonbank state lenders have different interpretations of

whether FCRA authorizes them to offer such programs. During our

review, CFPB had not determined if it would clarify these uncertainties for

nonbank state lenders and other nonbank private student loan lenders.

Providing such clarity could—depending on CFPB’s interpretation—result

in additional lenders offering rehabilitation (allowing more borrowers the

33

The Department of Education offers federal student loan borrowers income-driven

repayment plans to repay loans. These plans set the monthly student loan payment at an

amount that is intended to be affordable based on a borrower’s income and family size.

34

Will Dobbie, Paul Goldsmith-Pinkham, Neale Mahoney, and Jae Song, “Bad Credit, No

Problem? Credit and Labor Market Consequences of Bad Credit Reports,” Federal

Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report No. 795 (2017); D.K. Musto, “What Happens

When Information Leaves a Market? Evidence from Postbankruptcy Consumers,” Journal

of Business, vol. 77 (2004): p. 725–48.

35

Musto, “What Happens When Information Leaves a Market?” p. 725–48. A private

student loan default may not signal the same amount of financial distress that a

bankruptcy signals, so removing information about a private student loan default from a

borrower’s credit report may have a smaller effect than removing a bankruptcy.

Conclusions

Page 26 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

opportunity to participate), or help to ensure that only entities deemed

eligible by CFPB to offer programs are doing so.

In addition, the Act does not explain what information on a consumer’s

credit report constitutes a private student loan “default” that may be

removed following the successful completion of a private student loan

rehabilitation program. Without clarification from CFPB—after consulting

with the prudential regulators and relevant industry groups—on what

information in a credit report constitutes a private student loan default that

may be removed, lenders may be inconsistent in the credit report

information they remove. As a result, variations in lenders’ interpretations

could have different effects on borrowers’ credit scores and credit

records, which could affect how they are treated by credit providers and

could also result in inconsistencies that affect the accuracy of credit

reporting data.

We are making the following two recommendations to CFPB:

The Director of CFPB should provide written clarification to nonbank

private student loan lenders on their authorities under FCRA to offer

private student loan rehabilitation programs that include removing

information from credit reports. (Recommendation 1)

The Director of CFPB, after consulting with the prudential regulators and

relevant industry groups, should provide written clarification on what

information in a consumer’s credit report constitutes a private student

loan reported “default” that may be removed after successful completion

of a private student loan rehabilitation program. (Recommendation 2)

We provided a draft copy of this report to CFPB, the Department of

Education, FDIC, the Federal Reserve, the Federal Trade Commission,

NCUA, OCC, and the Department of the Treasury for review and

comment. We also provided FICO and VantageScore excerpts of the

draft report for review and comment. CFPB and NCUA provided written

comments, which have been reproduced in appendixes II and III,

respectively. FDIC, the Federal Trade Commission, OCC, and the

Department of the Treasury provided technical comments on the draft

report, which we have incorporated, as appropriate. The Department of

Education and the Federal Reserve did not provide any comments on the

draft of this report. FICO and VantageScore provided technical

comments, which we have incorporated, as appropriate.

Recommendations for

Executive Action

Agency Comments

and Our Evaluation

Page 27 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

In its written response, CFPB stated that it does not plan to act on our first

recommendation to provide written clarification to nonbank private student

loan lenders on their authorities under FCRA to offer private student loan

rehabilitation programs. CFPB stated—and we agree—that the Act does

not regulate the authority of private student loan lenders that are not

included in FCRA’s definition of a “financial institution,” nor direct financial

institutions that are not supervised by a federal banking agency to seek

CFPB’s approval concerning the terms and conditions of rehabilitation

programs. However, CFPB’s written response does not discuss the

authority of private student loan lenders that potentially fall outside

FCRA’s definition of a financial institution to offer rehabilitation programs

that include removing information from credit reports. As we discuss in

the report, uncertainty exists among nonbank private student loan lenders

regarding their authority to implement such programs. We maintain that

although the Act does not require CFPB to act on this issue, CFPB could

play a role in clarifying whether FCRA authorizes nonbanks to offer

rehabilitation programs that enable the lender to obtain legal protection

for removal of default information from a credit report. CFPB intervention

is warranted given the lack of clarity in the private student lending industry

and is consistent with CFPB’s supervisory authority over nonbank

financial institutions and its FCRA enforcement and rulemaking

authorities. We do not suggest that CFPB play a role in approving

rehabilitation programs. As we note in the report, clarification of

nonbanks’ authorities could result in additional lenders offering

rehabilitation programs and providing more consistent opportunities for

private student loan borrowers, or it could help ensure that only those

entities authorized to offer programs are doing so.

With respect to our second recommendation on providing written

clarification on what information in a consumer’s credit report constitutes

a private student loan reported default that may be removed after

successful completion of a private student loan rehabilitation program,

CFPB’s letter states that such clarification is premature because of

ongoing work by the Consumer Data Industry Association. The letter

states that after that work is completed, CFPB will consult with the

relevant regulators and other interested parties to determine if additional

guidance or clarification is needed. As we stated in the report, we are

aware of the work of the Consumer Data Industry Association to update

the credit reporting guidelines for private student loans. We maintain that

this work presents a good opportunity for CFPB to participate in these

discussions and to work in conjunction with the industry and other

relevant regulators to help alleviate any contradiction between what

CFPB would determine in isolation from any determination made by

Page 28 GAO-19-430 Private Student Loans

industry. Further, such participation would allow CFPB to weigh in on

legal and policy issues from the start, potentially avoiding any need for

future rulemaking. In addition, CFPB’s involvement in this determination

and issuance of clarification would help ensure more consistent treatment

among borrowers participating in private student loan rehabilitation

programs, as well as consistency in credit reporting information.